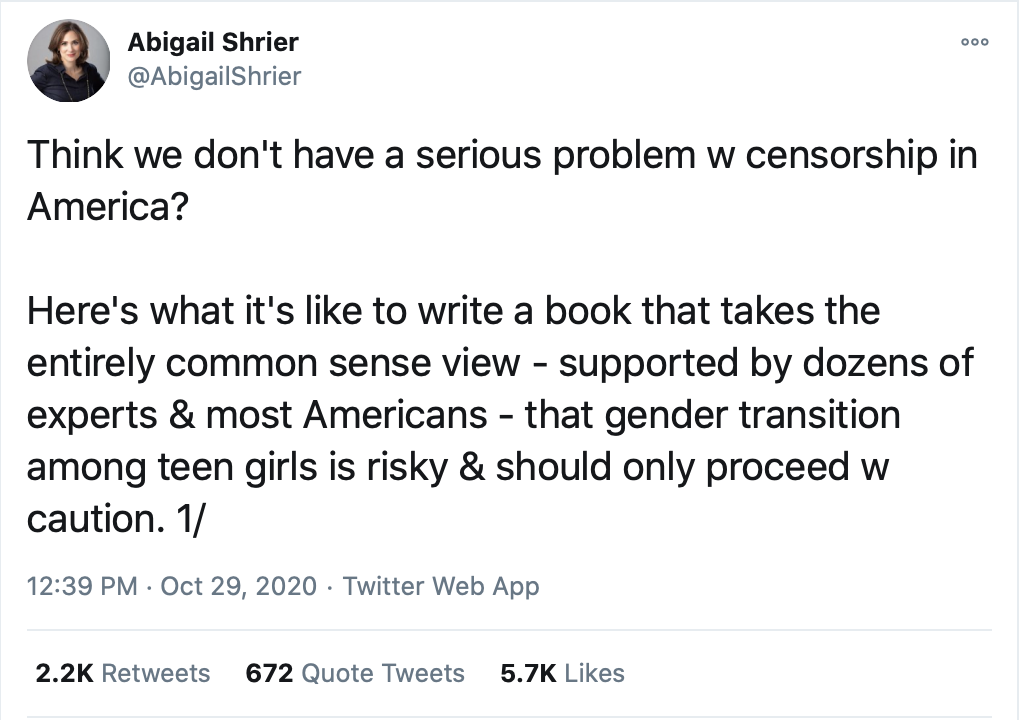

In today's WSJ, Abigail Shrier describes the environment into which she released her book, Irreversible Damage:

Social contagions exist, and teen girls are particularly susceptible to them. The book takes a hard look at whether the sudden spike in transgender identification among teen girls is yet another social contagion to befall girls who, in another era, might have fallen prey to anorexia or bulimia . . .Many transgender adults, including some I interviewed for the book, agree that teen girls are undergoing medical transition too fast with too little oversight. Others disagree and have written books. Amid a sea of material unskeptically promoting medical transition for teenage girls, there’s one book that investigates this phenomenon and urges caution. That is the book the activists seek to suppress.

The WSJ article is titled: "Does the ACLU Want to Ban My Book?"

Despite the importance of Shrier's book, it is being treated as though it an attempt to harm teenage girls when it is actually providing critically important information aimed at protecting teenaged girls as well as encouraging a much needed conversation.

There is nothing hateful in suggesting that most teenagers are not in a good position to approve irreversible alterations to their bodies, particularly if they are suffering from trauma, OCD, depression, or any of the other mental-health problems that are comorbid with expressions of dysphoria. And yet, here we are.

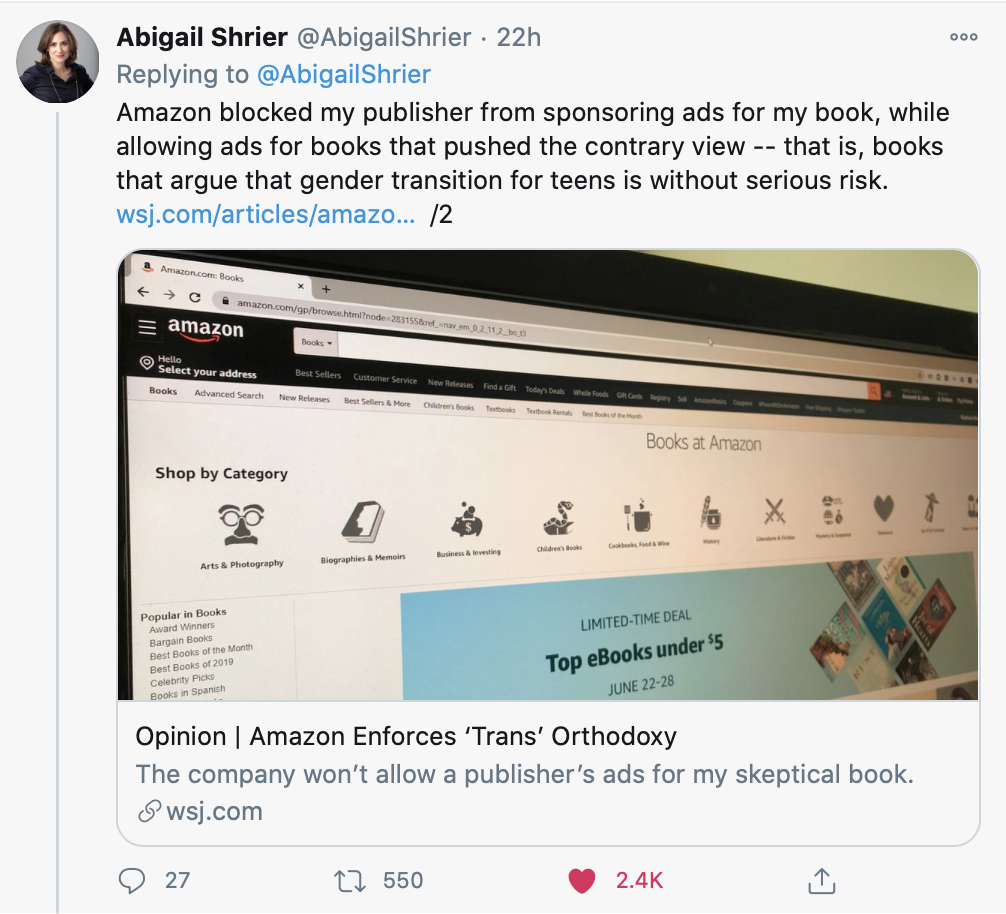

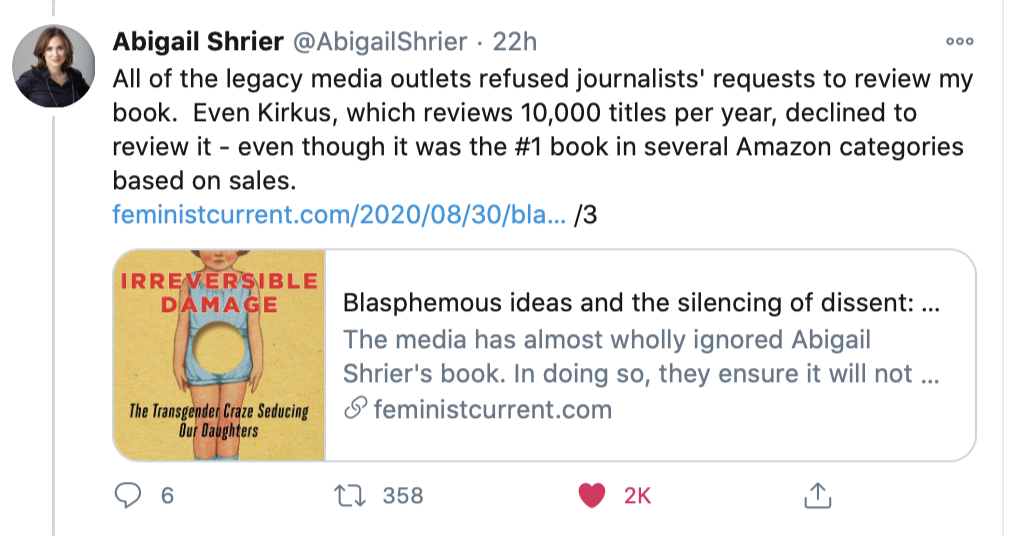

Target removed Irreversible Damage from its shelves this week, until it received an uproar from Twitter supporters of Shrier's right to promote her concerns. This is despite the fact that Robin DiAngelo's blatantly racist book, White Fragility, has been freely available at Target. Amazon has refused to allow Schrier's publisher to advertise her book on its site despite the fact that Irreversible Damage is the #1 book in several categories at Amazon. Newspapers and magazines are refusing to review Irreversible Damage:

In any case, every major newspaper and legacy magazine summarily turned interested journalists down. Whether they would have reviewed my book favorably or unfavorably, I have no idea—and it doesn’t matter. Kirkus, which reviews 10,000 titles per year, including self-published and obscure works—pretended my book didn’t exist. Its editors, too busy heaping praise on the Trans Teen Survival Guide, When Aiden Became a Brother, Jack (Not Jackie), Rethinking Normal, and of course, Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out.

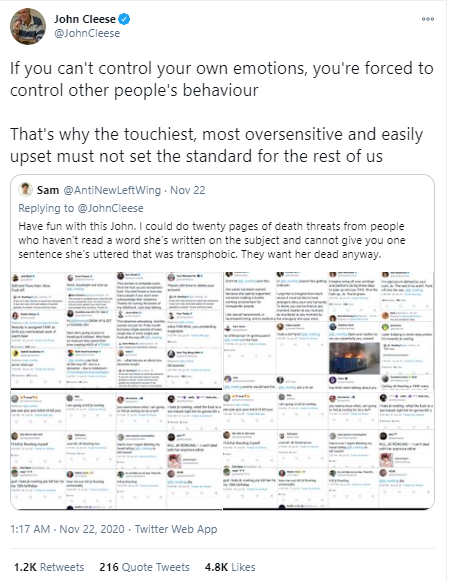

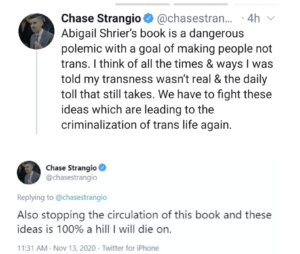

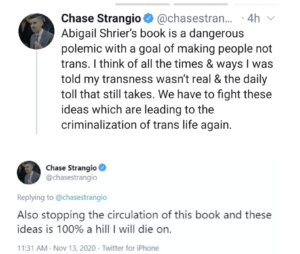

Two days ago, Chase Strangio of the "free speech" ACLU Tweeted that Shrier's book should be censored.

This is the sort of Tweet on posts when one has not actually read Shrier's book. I am halfway thru her book (and I had seen her lengthy interview with Joe Rogan). Strangio's Tweet completely mischaracterized Shrier's book, which shows absolute deference to the personal decisions of transgender adults. She urges that they should all receive the full protection under the law.

In response to Strangio's outrageously false Tweet, Glenn Greenwald writes:

It is nothing short of horrifying, but sadly also completely unsurprising, to see an ACLU lawyer proclaim his devotion to “stopping the circulation of [a] book” because he regards its ideas as wrong and dangerous. There are, always have been, and always will be people who want to stop books from being circulated: by banning them, burning them, pressuring publishing houses to rescind publishing contracts or demanding corporations refuse to sell them. But why would someone with such censorious attitudes, with a goal of suppressing ideas with which they disagree, choose to go to work for the ACLU of all places?

As far the claim that Shrier is engaging in "hate speech," consider this excerpt from her recent article at Quillette "Gender Activists Are Trying to Cancel My Book. Why is Silicon Valley Helping Them?"

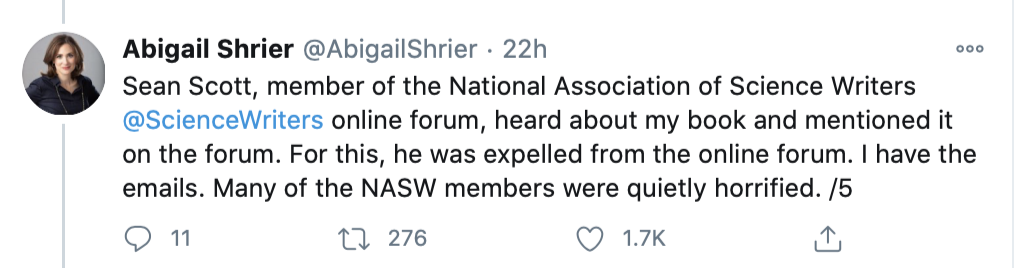

Sean Scott, a member of the National Association of Science Writers (NASW), heard of my book in the fall, and shared what he knew with other science writers. He noted that Nature Communications had published a study “to investigate whether autistic traits were elevated in transgender and gender-diverse individuals.” (To no one’s surprise, they are: Autistic children develop all kinds of strongly expressed fixations about the world they perceive.) Then he wrote: “This, along with [Wall Street Journal] columnist [Abigail Shrier’s] recent book on the onset of transgenderism amongst young girls… should hopefully shed some overdue light on a very sensitive, politically charged topic that potentially carries lifelong medical consequences.” Sound like hate speech? I didn’t think so.

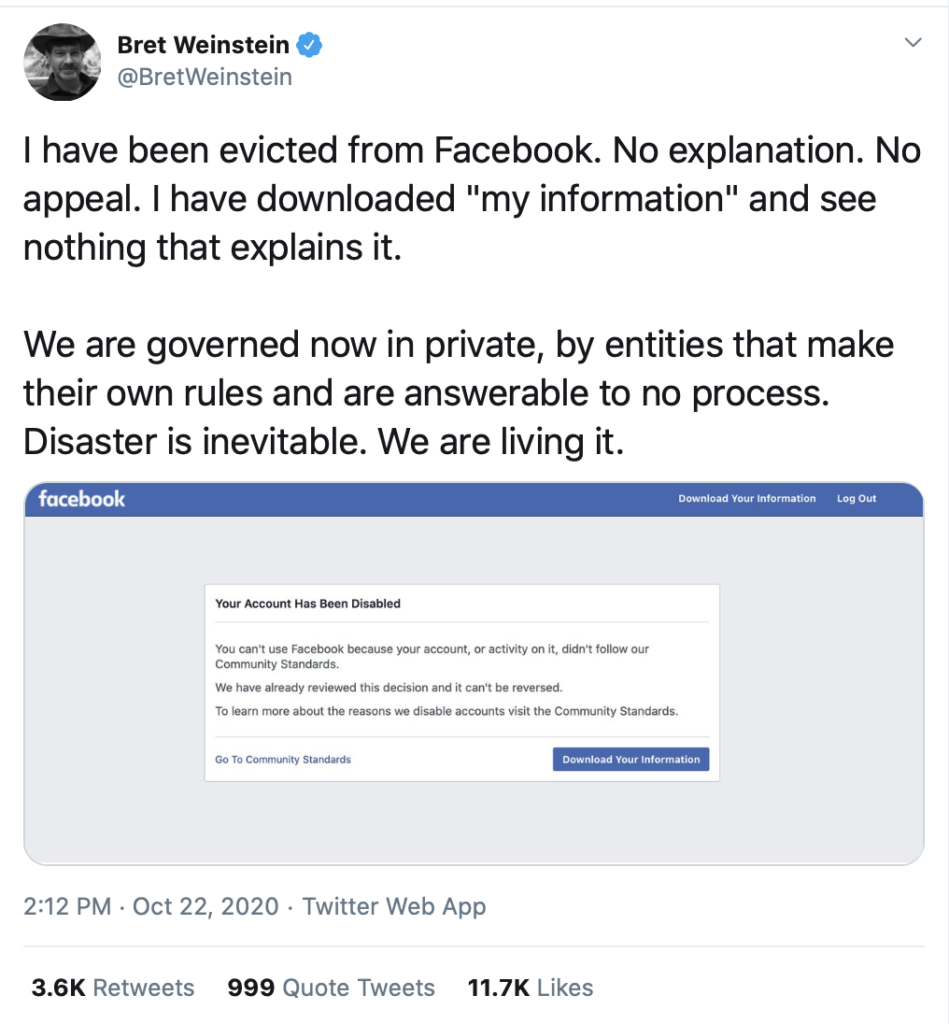

This saga will continue with the political Left increasingly embracing its new role as the anti-free-speech party. The Left is showing an increased willingness cancel good-hearted people based on false pretenses and an exuberant willingness to peddle faux science at least as well as any nut job on the political Right. And perhaps even better than the political Right.

As noted by Shrier in Quillette, she has received much support from parents who are seeing signs of transgender social contagion in their daughters. The sought to share this information with other concerned parents. GoFundMe quickly shut down these efforts:

Parents who’ve lived through this social contagion—who’d seen it strike daughters who’d never before exhibited signs of gender dysphoria in childhood—became so alarmed at suppression efforts that they dug into their own pockets to promote my work. That’s how I became one of the few authors in the world to have her own billboard in West Hollywood. Other parents started an account on GoFundMe, a website that facilitates fundraising efforts for all sorts of causes. GoFundMe closed the account. The parents started another campaign. GoFundMe closed that account, too. If a mentally fragile 18-year-old wants help removing her healthy breasts, GoFundMe will happily facilitate it. (The site currently hosts over 35,000 campaigns to pay for female “top surgery” alone.) But if you believe your daughter has become caught up in a movement that will leave her angry, regretful, maimed, and sterile, you’re out of luck.

This saga will continue with the political Left increasingly embracing its new role as the anti-free-speech party. The Left is showing an increased willingness cancel good-hearted people based on false pretenses and an exuberant willingness to peddle faux science at least as well as any nut job on the political Right. And perhaps even better than the political Right.

Where do you draw your line? When are you going muster the courage to speak out against the excesses of Woke culture? Is it when an Attorney for the ACLU actively seeks to ban an important well-researched book by a good-hearted woman? Yes, I'm referring to the ACLU, whose core principle is advocating for free speech. Or is it when there is a concerted nationwide effort (including Amazon, Target and GoFundMe) to refuse to allow discussion of blatantly anti-scientific claims that endanger millions of teenage girls in the U.S.? Not long ago, only 1 in 10,000 people were diagnosed with sexual disphoria. Are we really willing to stand by when 2% of teenagers have now been convinced by activists on social media and disreputable profit-taking healthcare providers that they were born in the wrong bodies?