My disorientation

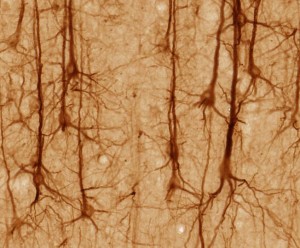

I’m finding myself to be disoriented tonight. You see, it has occurred to me (as it sometimes does) that I’m actually an incredibly complex community of trillions of individual cells, no single one of which is capable of having any conscious thought, though I am easily able to think consciously as a complex adaptive system of cells.

I'm also disoriented because it occurs to me tonight that this community of that is “me” is kept alive and conscious by an internal pulsing ocean of blood, its composition very much like the Earth’s oceans, which were apparently our ancestral home. Equally amazing, this internal ocean of blood is pumped through 60,000 mile of blood vessels by a heart that beats 100,000 each day, thanks to our incredibly reliable pacemaker cells. How can any of this possibly be true, except that it is true, because I am writing this post and you are reading it?

It also occurs to me that there are far too many other parts of my human body that I almost always take for granted, such as my liver, which continuously performs hundreds of chemical processes without any conscious help from “me" (not that I could possibly be of assistance). Even more amazing, the liver can repair itself. How is any of this remotely possible?

There are many other things on my mind tonight, all of which disorient me, because I'm trying to clear out my preconceptions and see these things as though I were seeing them for the first time. For instance, I seem to have evolved from viruses, which is mind-blowing. Actually, half of all human DNA originally came from viruses which embedded themselves into my ancestor’s gametes.

But I'm not done describing my disorientation. I am also disoriented tonight because I've reminded myself that some of my ancestors were sponges. No, they didn’t just look like sponges; they were sponges. And once cells figured out how to thrive together in that primitive sponge-like way, things rapidly got far more interesting. This real-world story of human gills, paws and fur is more amazing than any fiction anyone could ever write.

Tonight, I am also thinking about several people I know who are fighting for their lives against illness. I sometimes hear their friends and family asking how it could happen that the patients got so sick. But I’ve got a different take on human frailty, sickness and death. I wonder how something so complex as the human body works at all. Ever. Truly, how is it that I can even wiggle one of my fingers?

But there’s yet more to my disorientation tonight. It also occurs to me that the community of cells that constitutes me is living on a huge rotating orb that revolves around a star so big that it makes the earth look like a speck.

But there's more. It seems that the universe in which we find ourselves is expanding, but from what? How did it get here? I don't trust any answers that I've ever heard. I'm assuming that some type of universe or multi-verse has always been here in one form or another, and that's admittedly my bald speculative assumption. I don't even know enough to have a belief on the topic.

It also disorients me that no one really knows why things exist in this way rather than in some other way or no way at all, although many people peddle simplistic answers--mere strings of words--in response to these basic questions.

The biggest reason I’m disoriented tonight is that it appears that we don’t even know how to ask the biggest questions--we betray our naive ways even by the way we describe such questions as "big." Our “whys” and "hows" are pale and shallow—we appear to be condemned to forever dabble with our conceptual metaphors in our attempts to understand our complicated existence. We seem to be trapped in our finite understanding, unable to ever get around our own corner. That's the way it seems to be to me tonight, and every time these sorts of thought come to mind.

I'm disoriented, but don't get me wrong. I'm not complaining. I am truly enjoying the ride. I never cease to be amazed.

But I'm not done describing my disorientation. I am also disoriented tonight because I've reminded myself that some of my ancestors were sponges. No, they didn’t just look like sponges; they were sponges. And once cells figured out how to thrive together in that primitive sponge-like way, things rapidly got far more interesting. This real-world story of human gills, paws and fur is more amazing than any fiction anyone could ever write.

Tonight, I am also thinking about several people I know who are fighting for their lives against illness. I sometimes hear their friends and family asking how it could happen that the patients got so sick. But I’ve got a different take on human frailty, sickness and death. I wonder how something so complex as the human body works at all. Ever. Truly, how is it that I can even wiggle one of my fingers?

But there’s yet more to my disorientation tonight. It also occurs to me that the community of cells that constitutes me is living on a huge rotating orb that revolves around a star so big that it makes the earth look like a speck.

But there's more. It seems that the universe in which we find ourselves is expanding, but from what? How did it get here? I don't trust any answers that I've ever heard. I'm assuming that some type of universe or multi-verse has always been here in one form or another, and that's admittedly my bald speculative assumption. I don't even know enough to have a belief on the topic.

It also disorients me that no one really knows why things exist in this way rather than in some other way or no way at all, although many people peddle simplistic answers--mere strings of words--in response to these basic questions.

The biggest reason I’m disoriented tonight is that it appears that we don’t even know how to ask the biggest questions--we betray our naive ways even by the way we describe such questions as "big." Our “whys” and "hows" are pale and shallow—we appear to be condemned to forever dabble with our conceptual metaphors in our attempts to understand our complicated existence. We seem to be trapped in our finite understanding, unable to ever get around our own corner. That's the way it seems to be to me tonight, and every time these sorts of thought come to mind.

I'm disoriented, but don't get me wrong. I'm not complaining. I am truly enjoying the ride. I never cease to be amazed.