Universal Yard Sign

For efficiency, we can take down most of the yard signs on display and replace them with this:

For efficiency, we can take down most of the yard signs on display and replace them with this:

Geoffrey Miller describes how we got here, and it seems like an impossible journey.

And there is most definitely a selection bias, because many people didn't make it and didn't reproduce. Here's how Thomas Hobbes might have summed up 100,000 generations of camping trips ". . . continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

I'm reading Robert Sapolsky's excellent 800-page book, Behave: THE BIOLOGY OF HUMANS AT OUR BEST AND WORST. He tells this story about his wife:

So we’re in the minivan, our kids in the back, my wife driving. And this complete jerk cuts us off, almost causing an accident, and in a way that makes it clear that it wasn’tdistractedness on his part, just sheer selfishness. My wife honks at him, and he flips us off. We’re livid, incensed. Asshole-where’s-the-cops-when-you-needthem, etc. And suddenly my wife announces that w e’re going to follow him, make him a little nervous. I’m still furious, but this doesn’t strike me as the most prudent thing in the world. Nonetheless, my wife starts trailing him, right on his rear.After a few minutes the guy’s driving evasively, but my wife’s on him. Finally both cars stop at a red light, one that we know is a long one. Another car is stopped in front of the villain. He’s not going anywhere. Suddenly my wife grabs something from the front seat divider, opens her door, and says, “Now he’sgoing to be sorry.”I rouse myself feebly— “Uh, honey, do you really think this is such a goo— ”But she’s out of the car, starts pounding on his window. I hurry over just in time to hear my wife say, “If you could do something that mean to another person, you probably need this,” in a venomous voice. She then flings something in the window. She returns to the car triumphant, just glorious.

“What did you throw in there!?”

She’s not talking yet. The light turns green, there’s no one behind us, and we just sit there. The thug’s car starts to blink a very sensible turn indicator, makes a slow turn, and heads down a side street into the dark at, like, five miles an hour. If it’s possible for a car to look ashamed, this car was doing it.

“Honey, what did you throw in there, tell me? ”

She allows herself a small, malicious grin.

“A grape lollipop.” I was awed by her savage passive aggressiveness— “You’re such a mean, awful human that something must have gone really wrong in your childhood, and maybe this lollipop will help correct that just a little.”That guy was going to think twice before screwing with us again. I swelled with pride and love.

Here's a rather amazing thing I recently learned about myself from 23 & Me: "You inherited a small amount of DNA from your Neanderthal ancestors. Out of the 7,462 variants we tested, we found 257 variants in your DNA that trace back to the Neanderthals." 23 & Me further told me I have up to 2% of Neanderthal DNA in my genome.

I've also checked out many hundreds of my 4th-6th cousins. They have many hundreds of last names and, based upon the profile photos, they come in every size, shape and skin color. They reside in dozens of countries all over the world. I have numerous relatives born in Africa, Asia and Australia. Six of my relatives are Egyptian. 34 of my closest 5,000 relatives are at least 25% Ashkenazi Jews.

As I'm learning these things, I'm recalling the joyous presentation A.J. Jacobs made about his expansive family tree at this TED talk.

That a company can reliably tell me these things for $99 would have been unfathomable even a few decades ago--It wasn't until 2003 that scientists could read the complete genetic blueprint for building a human being (the Human Genome Project). These findings and this modest cost to learn these things are stunning. So stunning that, as I found ever more about my family tree tonight, I even chuckled a little Neanderthal chuckle.

When you arrive at the doctor's office to check in with the receptionist, you are often handed a small pack of paperwork to fill out. Until that moment, you have probably been focused on your own ailment or your own medical worries. Luckily, for most of us--most of the time--our own health concerns will more or less resolve and life will more or less go on.

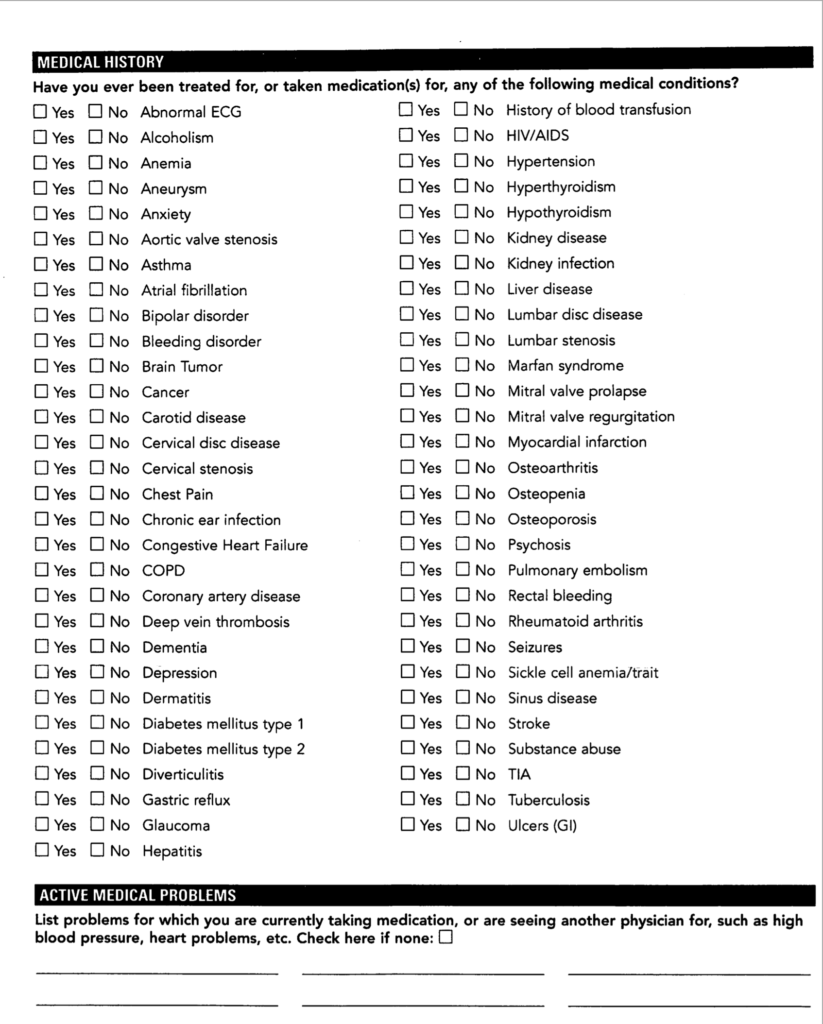

For all of us, however, that typical pack of doctor office paperwork contains a magic page that has the power to boost our happiness through the roof, if only we employ the correct frame of gratitude. I'm referring to the page that looks something like this:

This page gives us the opportunity to breathe a cosmic sigh of relief that we do not have most of those ailments on that list. That's how I try to see it as I check off all most of those boxes with a "no." Thank goodness I don't have most of those medical problems. And this is merely the beginning of what I'm proposing as a journey of gratitude.

Instead of thinking about my own health problem, instead of being frustrated that my own body is not operating perfectly, the above page is a reminder that my body is an extraordinarily complex adaptive system--lots of little parts have self-organized into something so complicated that it seems miraculous. No humans could possibly make a tongue or an eye or a liver as high functioning or as elegant as the natural versions.

Imagine that humans in the distant future worked very hard and came much closer to making a reasonably functioning robotic human. Then imagine their supervisors sending down a new work order to make sure that this robot is also sentient. Imaging the groaning you would hear from the engineering team! Then imagine that the supervisors send down another new work order to make sure that this artificial human could also repair itself if it became damaged! Imaging louder groaning, especially when the supervisors remind the team that this self-repair must respond to hundreds of millions of microscopic threats and do it as well as the human immune system.

Then imagine that the supervisors send down yet another work order advising the team that they must design their human so that it runs on almost anything that it puts in its mouth. Even louder groaning. Mutiny is threatened.

Finally, thousands of years later, when millions more engineers (and their great great great great grand-engineers) have successfully created a passable artificial human, the supervisors call down with one more new request: Make sure that these artificial humans can create tiny artificial humans the size of a pinpoint that will grow, within the body of one of the robots, into large artificial humans who become wise through their interactions with any of dozens of environments. Then imagine all the engineers quitting their jobs.

At the doctor's office, our question should not be "Why doesn't my body work perfectly?" We shouldn't even complain that we sometimes have one or more of those ailments on the long checklist handed to us by the doctor's receptionist. A better question is "How is it possible that the actions of countless individual molecules self-organize into trillions of cells that result in emergent coordinated macroscopic behaviors such as the ability to walk into a doctor's office?" Even more simply, the first question should always be "How is it possible that human bodies work at all, ever?"

Answer not forthcoming.