Argument Fallacy Referee Images

Love these referee images. They cover all the most popular argument fallacies, including Ad Hominem, Moving the Goalpost, Guilt by Association and Red Herring.

Love these referee images. They cover all the most popular argument fallacies, including Ad Hominem, Moving the Goalpost, Guilt by Association and Red Herring.

Here's the quadruple whammy:

A) Confirmation Bias, B) Availability Heuristic and C) the Focussing Illusion and D) In-group loyalties.

These add up to an extremely dangerous personal hubris that we have no blindspots, that we know everything we need to know, and that our ideas are fully tested whereas we have simply enshrined them in our own brains, surrounding them with mental electrified fences. We need THIS daily vitamin: Our ideas need to be repeatedly tested by numerous uninterested or antagonistic OTHERS. We often commit medical malpractice when we pretend we are world-class doctors who can adequately diagnose our own thought processes.

I am fatiguing from meeting people who never ever doubt their mental hygiene and never worry about the need to run meaningful real-world tests on their own ideas. I'm getting worn out watching people bark at each other on FB instead of showing humility and a willingness to learn from each other. I want to ask so many people on FB: "Why are you here? To learn something new or merely to strut around looking for fully cooked allies?"

In "How to converse with know-it-alls," Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay suggest techniques for dealing with know-it-alls. Know-it-allness is often caused by the Dunning-Kruger Effect (which the authors also call "the Unread Library Effect" and cognitive scientists call "the illusion of explanatory depth."

Kruger and Dunning proposed that, for a given skill, incompetent people will:

1. tend to overestimate their own level of skill; 2. fail to recognize genuine skill in others; 3. fail to recognize the extremity of their inadequacy; 4. recognize and acknowledge their own previous lack of skill, if they can be trained to substantially improve.

How do you show know-it-alls that they don't know as much as they think they know? Boghossian and Lindsay suggest that we ask them to explain their claims in detail.

[R]esearchers asked people to rate how confident they were in their ability to describe how a toilet works. Once subjects provided answers, experimenters had them write down as many details as they could in a short essay, and then they were again asked about their confidence. Their self-reported confidence dropped significantly after attempting to explain the inner workings of toilets. People know there’s a library of information out there explaining things — they just haven’t read it! Exposing the flimsiness of their knowledge is a simple matter of letting them discover it for themselves.

One most easily does this by asking know-it-alls to explain their claims in detail:

Whether it’s gun control legislation, immigration policy, or China trade tariffs — and have them provide as many technical details as they can. How, exactly, does it work? How will change be implemented? Who will pay for it? What agencies will oversee it? . . . People become less certain, question themselves more, and open their minds to new possibilities when they realize they know less than they thought they knew.

Just politely ask straightforward question and insist on answers that you can understand. Keep an open mind. Perhaps they will convince you that they are correct! If you are not convinced, however, be patient and follow up with more questions. If the conversation goes on and on, don't allow your fatigue to get the best of you. Don't ever indicate that you understand when you don't. That would not be helping anybody.

As I was reading the above article, I researched other ideas I could add to this post. The authors of, "An expert on human blind spots gives advice on how to think" discussed the DK effect with David Dunning, who warned of the First rule of the Dunning-Kruger Club: "people don’t know they're members of the Dunning-Kruger Club." These people lack "Intellectual Humility." In other words, they assume they are correct, which means (to them) that there is no need to seek out and correct their intellectual blind spots.

Dunning offered this additional advice for dealing with people in the DK Club. One bit of advice is to challenge the know-it-all to think in terms of probabilities:

[P]eople who think not in terms of certainties but in terms of probabilities tend to do much better in forecasting and anticipating what is going to happen in the world than people who think in certainties.

Dunning warns that many people don't "make the distinctions between facts and opinion." People are increasingly creating not only their own opinions, but their own facts.Yet another problem listed by Dunning is that people are increasingly unwilling to say "I don't know." Trying to get people to say that they don't know when they don't know is a serious and so far unsolvable problem. It would seem, then, that cross-examining the know-it-all as to the source of their information is critical.

Dunning also suggests a downside to getting things correct: "To get something really right, you’ve got to be overly obsessive and compulsive about it." In other words, it's not easy to get facts correct on a complex issue. It takes work. Those people who are more accurate take the time to ask themselves whether and how they could be wrong. "How can your plans end up in disaster?" Know-it-alls fail to show this concern that it often takes a lot of work to get to the truth.

Finally, in a nod to John Stuart Mill's On Liberty, Dunning states that it's important to realize that one is better off to invite others to test one's ideas. Dunning states: "We’re making decisions as our own island, if you will. And if we consult, chat, schmooze with other

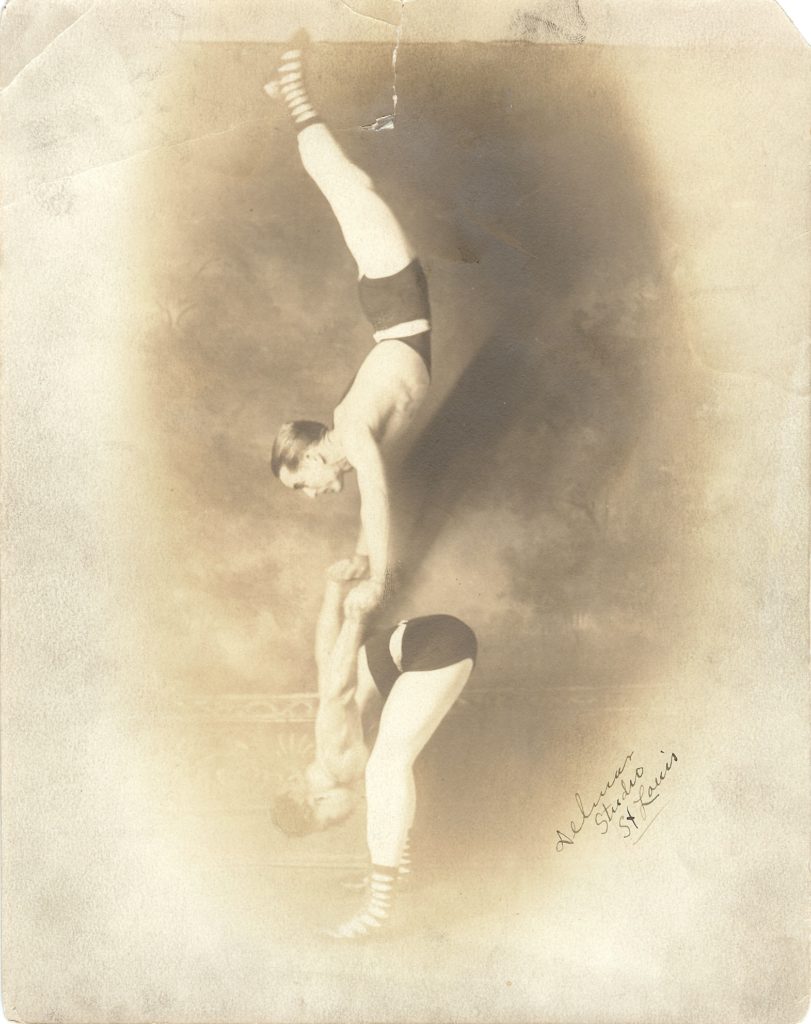

My grandfather, Robert Wich, was an amateur gymnast. Below, you'll see a photo of him doing a routine with his gymnastics partner (I'm assuming that this photo was taken in the early 1920's My grandfather is the one in the air).

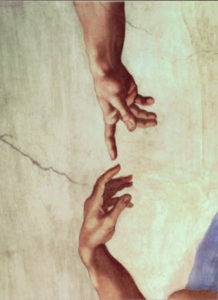

I am trying to respect this family tradition, but I find it easier to do impressive acrobatics in my own way at the Oto-phay Op-Shay Branch of the YMCA. Here I am performing the rarely seen finger-balancing routine with my gymnastics partner, Edie White. I'm also attaching a close-up so you can appreciate the critical placement of fingers.

I enthusiastically recommend this podcast featuring Donald Hoffman. Sam Harris and (his wife) Annaka sound, in equal parts, skeptical and intrigued, which makes for some deeply engaging conversation. Hoffman's thesis might challenge almost everything you think. Hoffman argues that evolution has not honed us to have veridical perception (seeing things as they really are). Rather, natural selection has privileged evolutionary fitness to prevail over veridicality. This topic dovetails nicely with Andy Clark's theory of predictive processing, in which Andy portrays perception as a "controlled hallucination."

The first hour is free for non-subscribers. Here's the promo for the podcast:

In this episode of the Making Sense podcast Sam and Annaka Harris speak with Donald Hoffman about his book The Case Against Reality. They discuss how evolution has failed to select for true perceptions of the world, his “interface theory” of perception, the primacy of math and logic, how space and time cannot be fundamental, the threat of epistemological skepticism, causality as a useful fiction, the hard problem of consciousness, agency, free will, panpsychism, a mathematics of conscious agents, philosophical idealism, death, psychedelics, the relationship between consciousness and mathematics, and many other topics.

Donald Hoffman is a professor of cognitive science at the University of California, Irvine. He is the author of more than 90 scientific papers and his writing has appeared in Scientific American, Edge.org, The Atlantic, WIRED, and Quanta. In 2015, he gave a mind-bending TED Talk titled, “Do we see reality as it is?”

Life is not an argument. We have arranged for ourselves a world in which we are able to live--by positing bodies, lines, planes, causes and effects, motion and rest, form and content; without these articles of faith no one could endure living! But that does not prove them. Life is not an argument; the conditions of life might include error