The Case for Investigating Anthony Fauci

Elon's Musk has announced that his "pronouns" are "Prosecute/Fauci." This is over the top for me, yet Musk has the right to say this and I have the right to criticize Musk that it's over the top. That's how free speech works. We don't yet know enough to prosecute Fauci. Maybe we never will. Maybe Fauci is completely innocent of the things Musk wants to "prosecute."

I don't know all the facts about Fauci, but I know enough of them to be suspicious. There are a LOT of suspicious facts. I want very much to get to the bottom of this because COVID disrupted the lives of billions of people and hurt or killed millions of them. Since when do we ignore calamitous situations just because someone calls them a conspiracy theory, someone like David Frum (who doesn't understand the import of major media coordinating with the U.S. spy state to squelch the story of Hunter Biden's laptop)? Stevemur wrote an excellent response to Frum:

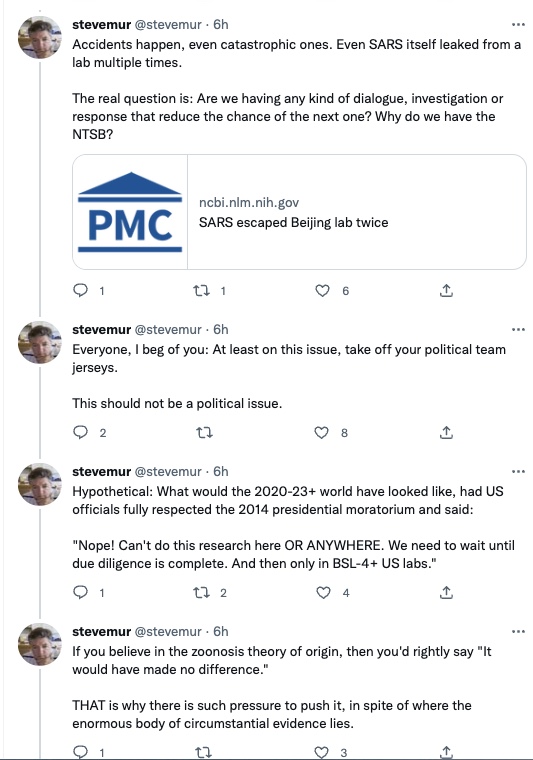

In invite you to walk through stevemur's thread, step by step, then ask yourself whether you too are suspicious. Note stevemur's conclusions: