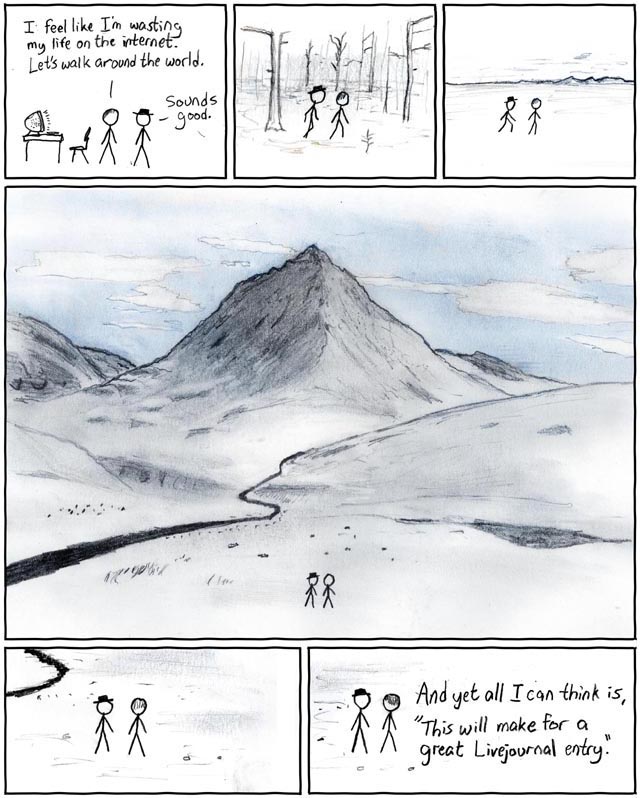

More evidence that the Internet is making us stupid

According to new book by Nicolas Carr, the brain's plasticity is a double-edge sword--to the extent that we make ourselves into Internet skimmers, we allow other cognitive abilities atrophy. Carr's new book was reviewed at Salon.com by Laura Miller:

The more of your brain you allocate to browsing, skimming, surfing and the incessant, low-grade decision-making characteristic of using the Web, the more puny and flaccid become the sectors devoted to "deep" thought. Furthermore, as Carr recently explained in a talk at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, distractibility is part of our genetic inheritance, a survival trait in the wild: "It's hard for us to pay attention," he said. "It goes against the native orientation of our minds."

Concentrated, linear thought doesn't come naturally to us, and the Web, with its countless spinning, dancing, blinking, multicolored and goodie-filled margins, tempts us away from it. (E-mail, that constant influx of the social acknowledgment craved by our monkey brains, may pose an even more potent diversion.) "It's possible to think deeply while surfing the Net," Carr writes, "but that's not the type of thinking the technology encourages or rewards." Instead, it tends to transform us into "lab rats constantly pressing levers to get tiny pellets of social or intellectual nourishment."

Rather than claim that the Internet makes us "stupid" (a term used in the title of an article on this topic that Carr published in The Atlantic, "Is Google Making Us Stupid?"), it would be more accurate to suggest that constant skimming and clicking develop those particular skills at the expense of the ability to focus deeply. Thus, we trade-off one ability for another, it seems, an idea captured by Howard Gardner's suggestion that it is misleading to speak of a unified version of intelligence--hence his concept of the multiple intelligences. There is no doubt that the ability to quickly navigate the Internet and to multitask can be quite useful in many situations. The question is whether a long-term development of these skimming and clicking skills, to the extent that it diminishes traditional skills associated with "intelligence," leads to the kinds of ideas and abilities that we need to solve modern day problems faced by society. This is an issue recently raised by Barack Obama:With iPods and iPads and Xboxes and PlayStations -- none of which I know how to work -- information becomes a distraction, a diversion, a form of entertainment, rather than a tool of empowerment, rather than the means of emancipation.

I notice that I am often not focusing well when I read on a screen, especially after long hours of looking at the screen. I find that my focus improves dramatically when I switch to printed material, especially when I also use a pen to ink up the article with my own highlights and notes. Perhaps this is another illustration of the same problem noted by Carr. Perhaps I will need to actually buy and read the print version of Carr's new book to fully appreciate his analysis! To complicate matters, I caught the above-linked potentially important ideas and articles while surfing the Internet.