When you arrive at the doctor's office to check in with the receptionist, you are often handed a small pack of paperwork to fill out. Until that moment, you have probably been focused on your own ailment or your own medical worries. Luckily, for most of us--most of the time--our own health concerns will more or less resolve and life will more or less go on.

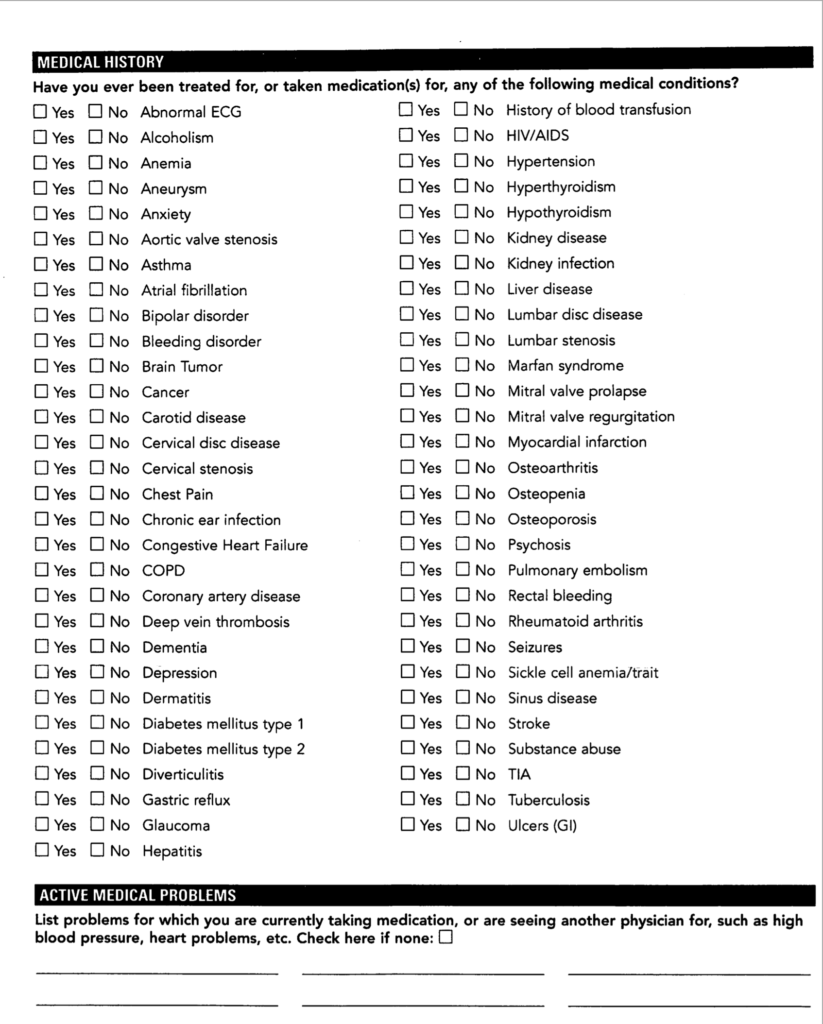

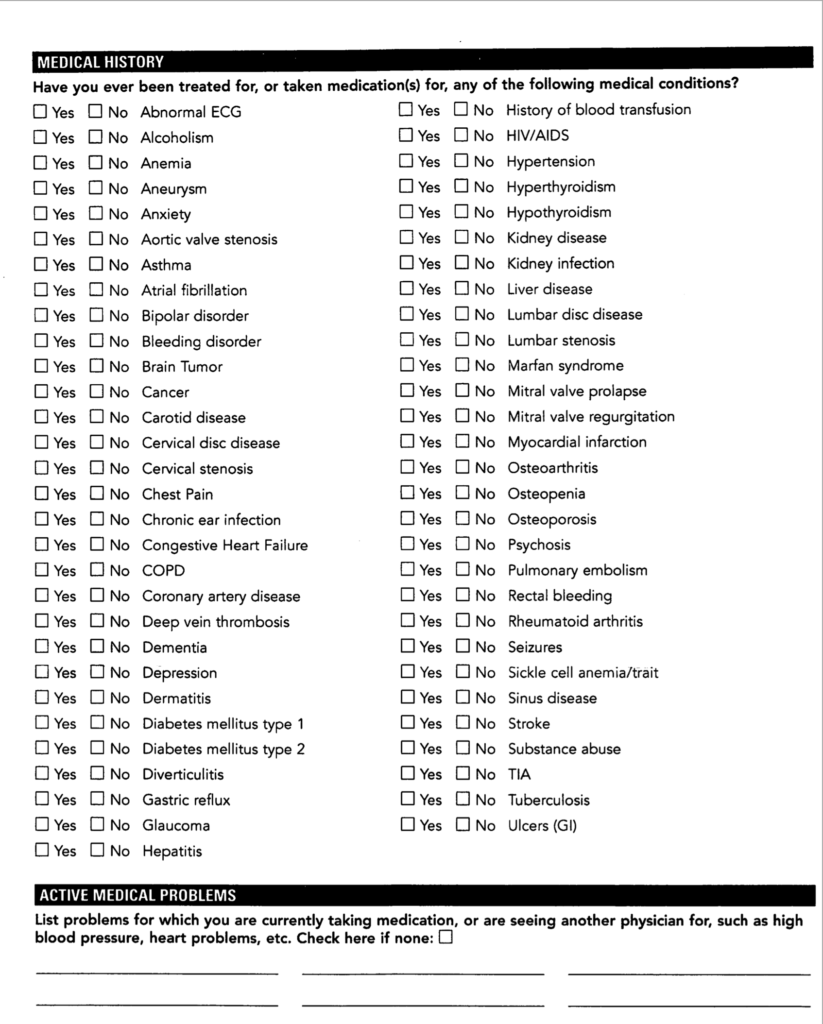

For all of us, however, that typical pack of doctor office paperwork contains a magic page that has the power to boost our happiness through the roof, if only we employ the correct frame of gratitude. I'm referring to the page that looks something like this:

This page gives us the opportunity to breathe a cosmic sigh of relief that we do not have most of those ailments on that list. That's how I try to see it as I check off all most of those boxes with a "no." Thank goodness I don't have most of those medical problems. And this is merely the beginning of what I'm proposing as a journey of gratitude.

Instead of thinking about my own health problem, instead of being frustrated that my own body is not operating perfectly, the above page is a reminder that my body is an extraordinarily complex adaptive system--lots of little parts have self-organized into something so complicated that it seems miraculous. No humans could possibly make a tongue or an eye or a liver as high functioning or as elegant as the natural versions.

Imagine that humans in the distant future worked very hard and came much closer to making a reasonably functioning robotic human. Then imagine their supervisors sending down a new work order to make sure that this robot is also sentient. Imaging the groaning you would hear from the engineering team! Then imagine that the supervisors send down another new work order to make sure that this artificial human could also repair itself if it became damaged! Imaging louder groaning, especially when the supervisors remind the team that this self-repair must respond to hundreds of millions of microscopic threats and do it as well as the human immune system.

Then imagine that the supervisors send down yet another work order advising the team that they must design their human so that it runs on almost anything that it puts in its mouth. Even louder groaning. Mutiny is threatened.

Finally, thousands of years later, when millions more engineers (and their great great great great grand-engineers) have successfully created a passable artificial human, the supervisors call down with one more new request: Make sure that these artificial humans can create tiny artificial humans the size of a pinpoint that will grow, within the body of one of the robots, into large artificial humans who become wise through their interactions with any of dozens of environments. Then imagine all the engineers quitting their jobs.

At the doctor's office, our question should not be "Why doesn't my body work perfectly?" We shouldn't even complain that we sometimes have one or more of those ailments on the long checklist handed to us by the doctor's receptionist. A better question is "How is it possible that the actions of countless individual molecules self-organize into trillions of cells that result in emergent coordinated macroscopic behaviors such as the ability to walk into a doctor's office?" Even more simply, the first question should always be "How is it possible that human bodies work at all, ever?"

Answer not forthcoming.