In her column at Psychology Today ("How to Train Your Boyfriend"), Evolutionary Psychologist Diane Fleischman illustrates the time investment differential in terms of money:

We know women have had to carry a baby for 9 months. But over our evolutionary history, a mother would have had to breastfeed for 3 years, on average, before the baby would be weaned. What's the minimum amount of investment a man could put in to have a baby? Let's be generous and say the minimum amount is an hour. This is called "minimum obligatory parental investment" and in human men and women, the asymmetry is bigger than in most other species. . . . If you think about the asymmetry between men and women in the minimum amount they would have to invest to make a baby in terms of dollar amount- a man would have to invest $1 and a woman would have to invest $32,000.

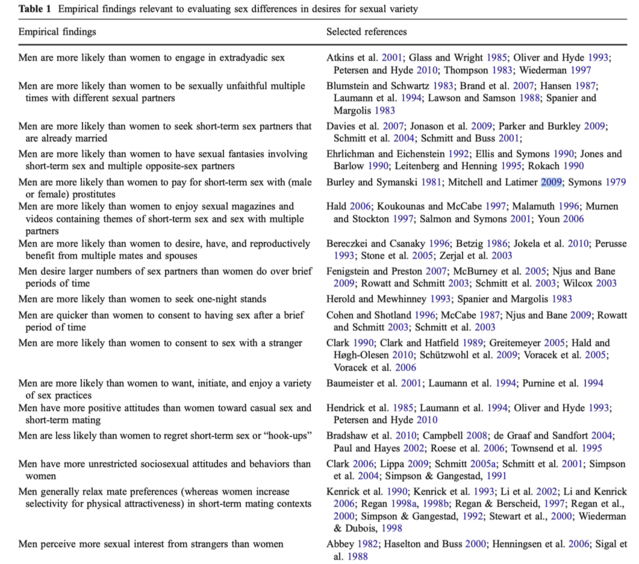

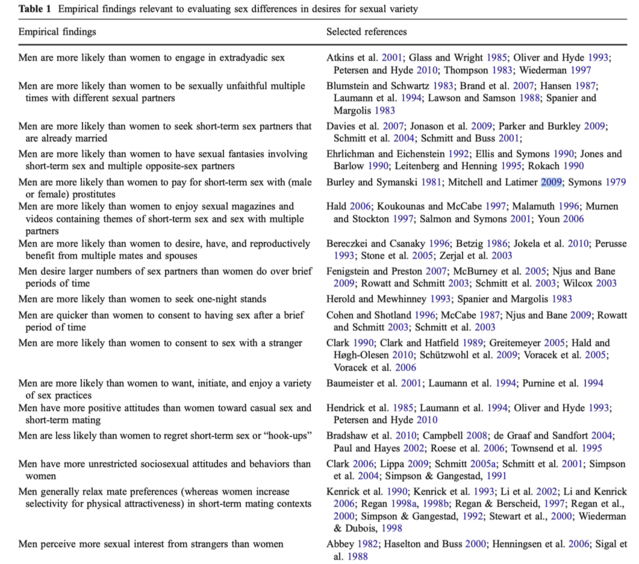

In her article, Fleishman points out many difference in behavior between men and woman (see the extensive list below), as well as reproductive risks, stemming from this procreation investment asymmetry.