Robots and human interaction

Last year, before I even heard of DI, I resolved to read all 15 of Isaac Asimov’s books/novels set within his Foundation universe this year. Why “before I even heard of DI”? Well, you may already know, but I won’t spoil the detective work if you don’t. (Hint: scroll down to the list about ¾ down the wiki page.) Why “this year”? I spent the summer and fall studying for an exam I had put off long enough and had little time for any outside reading.

I read I, Robot nearly 40 years ago, and The Rest of the Robots some time after that, followed by the Foundation trilogy, Foundation’s Edge when it was published in 1982, and Prelude to Foundation when it was published in 1988. I never read any of the Galactic Empire novels or the rest of the Foundation canon, and none of the “Robot novels”, which is why I decided to read them all, as Asimov laid out the timeline. I do like to re-read books, but hadn’t ever re-read any of the robot short stories, even when I added The Complete Robot to my collection in the early 1980s. As I’ve slept a bit since the first read, I forgot much, particularly how Asimov imagined people in the future might view robots.

Many recognize Asimov as one of the grandmasters of robot science fiction, (any geek knows the Three Laws of Robotics; in fact Asimov is credited with coining the word “robotics”). He wrote many of his short stories in the 1940s when robots were only fiction. I promise not to go into the plots, but without spoiling anything, I want to touch on a recurrent theme throughout Asimov’s short stories (and at least his first novel…I haven’t read the others yet): a pervasive fear and distrust of robots by the people of Earth. Humankind’s adventurous element - those that colonized other planets - were not hampered so, but the mother planet’s population had an irrational Frankenstein complex (named by the author, but for reasons unknown to most of the characters being that it is an ancient story in their timelines). Afraid that the machines would take jobs, harm people (despite the three laws), be responsible for the moral decline of society, robots were accepted and appreciated by few (on Earth that is.) {note: the photo is the robot Maria from Fritz Lang's "Metropolis", now in the public domain.}

Many recognize Asimov as one of the grandmasters of robot science fiction, (any geek knows the Three Laws of Robotics; in fact Asimov is credited with coining the word “robotics”). He wrote many of his short stories in the 1940s when robots were only fiction. I promise not to go into the plots, but without spoiling anything, I want to touch on a recurrent theme throughout Asimov’s short stories (and at least his first novel…I haven’t read the others yet): a pervasive fear and distrust of robots by the people of Earth. Humankind’s adventurous element - those that colonized other planets - were not hampered so, but the mother planet’s population had an irrational Frankenstein complex (named by the author, but for reasons unknown to most of the characters being that it is an ancient story in their timelines). Afraid that the machines would take jobs, harm people (despite the three laws), be responsible for the moral decline of society, robots were accepted and appreciated by few (on Earth that is.) {note: the photo is the robot Maria from Fritz Lang's "Metropolis", now in the public domain.}

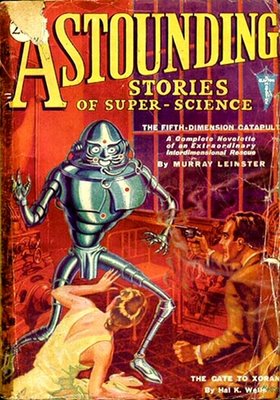

Robots in the 1940s and 1950s pulp fiction and sci-fi films were generally menacing like Gort in the 1951 classic, The Day the Earth Stood Still, reinforcing that Frankenstein complex that Asimov explored. Or functional like one of the most famous robots in science fiction, Robbie in The Forbidden Planet, or “Robot” in Lost in Space who always seemed to be warning Will Robinson of "Danger!"

When writing this, I remembered Silent Running, a 1972 film with an environmental message and Huey, Dewey and Louie, small, endearing robots with simple missions, not too unlike Wall-E. Yes, robots were bad again in The Terminator, but we can probably point to 1977 as the point at which robots forever took on both a new enduring persona and a new nickname – droids. {1931 Astounding was published without copyright}

Why the sketchy history lesson (here's another, and a BBC very selective "exploration of the evolution of robots in science fiction")? It was Star Wars that inspired Dr. Cynthia Breazel, author of Designing Sociable Robots, as a ten year old girl to later develop interactive robots at MIT. Her TED Talk at December 2010’s TEDWomen shows some of the incredible work she has done, and some of the amazing findings on how humans interact.

Very interesting that people trusted the robots more than the alternative resources provided in Dr. Breazel’s experiments.

Asimov died in 1992, so he did get to see true robotics become a reality. IBM’s Watson recently demonstrated its considerable ability to understand and interact with humans and is now moving on to the Columbia University Medical Center and the University of Maryland School of Medicine to work with diagnosing and patient interaction.

Imagine the possibilities…with Watson, and Dr. Breazel’s and others’ advances in robotics, I think Asimov would be quite pleased that his fears of human robo-phobia were without … I can’t resist…Foundation.

Robots in the 1940s and 1950s pulp fiction and sci-fi films were generally menacing like Gort in the 1951 classic, The Day the Earth Stood Still, reinforcing that Frankenstein complex that Asimov explored. Or functional like one of the most famous robots in science fiction, Robbie in The Forbidden Planet, or “Robot” in Lost in Space who always seemed to be warning Will Robinson of "Danger!"

When writing this, I remembered Silent Running, a 1972 film with an environmental message and Huey, Dewey and Louie, small, endearing robots with simple missions, not too unlike Wall-E. Yes, robots were bad again in The Terminator, but we can probably point to 1977 as the point at which robots forever took on both a new enduring persona and a new nickname – droids. {1931 Astounding was published without copyright}

Why the sketchy history lesson (here's another, and a BBC very selective "exploration of the evolution of robots in science fiction")? It was Star Wars that inspired Dr. Cynthia Breazel, author of Designing Sociable Robots, as a ten year old girl to later develop interactive robots at MIT. Her TED Talk at December 2010’s TEDWomen shows some of the incredible work she has done, and some of the amazing findings on how humans interact.

Very interesting that people trusted the robots more than the alternative resources provided in Dr. Breazel’s experiments.

Asimov died in 1992, so he did get to see true robotics become a reality. IBM’s Watson recently demonstrated its considerable ability to understand and interact with humans and is now moving on to the Columbia University Medical Center and the University of Maryland School of Medicine to work with diagnosing and patient interaction.

Imagine the possibilities…with Watson, and Dr. Breazel’s and others’ advances in robotics, I think Asimov would be quite pleased that his fears of human robo-phobia were without … I can’t resist…Foundation.