I love libraries. More to the point, I love books. My wife also loves books, though now prefers her phone app to read when she gets the chance. I do read texts occasionally on my phone, and used to on my Palm, and I reluctantly read on/offline docs, but I prefer tradition.

I love libraries. More to the point, I love books. My wife also loves books, though now prefers her phone app to read when she gets the chance. I do read texts occasionally on my phone, and used to on my Palm, and I reluctantly read on/offline docs, but I prefer tradition. There are many reasons for going to libraries. I rarely use them for research anymore. I only go for a specific book maybe 20% of the time. I delight in taking in the experience and seeing where it leads me. I might have an objective in mind, but there are so many opportunities awaiting me, it’s hard to choose just one, or two, or several!

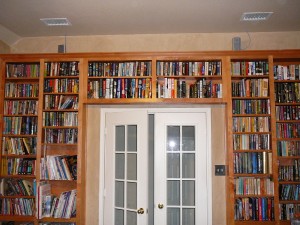

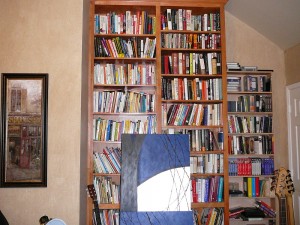

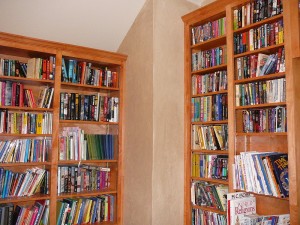

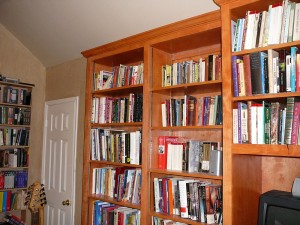

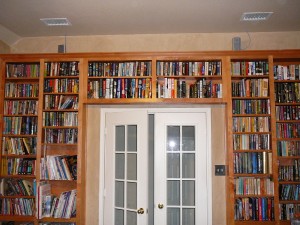

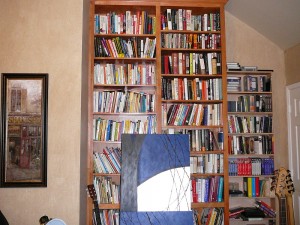

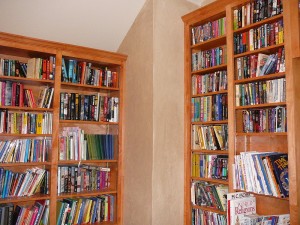

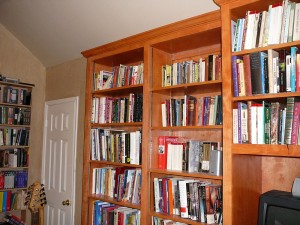

My own library

There are many reasons for going to libraries. I rarely use them for research anymore. I only go for a specific book maybe 20% of the time. I delight in taking in the experience and seeing where it leads me. I might have an objective in mind, but there are so many opportunities awaiting me, it’s hard to choose just one, or two, or several!

My own library  is not dissimilar from a public or university library in that respect, save perhaps its scale. That and it also serves as a music room (drum set, guitars, keyboard...) and an occasional media room. We have more than 5,300 books, though about 1,000 of them are for very young children (and mostly packed away now) and another 500 for young adults – combination homeschooling and love of books. I was putting books away the other night and looking for some references on homeschooling for a couple of pieces I am writing and went on a mini-adventure (every re-shelving trip up to my library results in armfuls coming back down with me)….

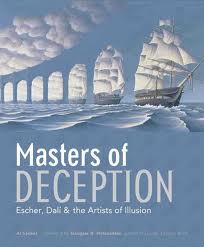

...I rediscovered

is not dissimilar from a public or university library in that respect, save perhaps its scale. That and it also serves as a music room (drum set, guitars, keyboard...) and an occasional media room. We have more than 5,300 books, though about 1,000 of them are for very young children (and mostly packed away now) and another 500 for young adults – combination homeschooling and love of books. I was putting books away the other night and looking for some references on homeschooling for a couple of pieces I am writing and went on a mini-adventure (every re-shelving trip up to my library results in armfuls coming back down with me)….

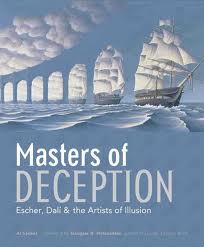

...I rediscovered  Masters of Deception, compiled by Al Seckel, is a wondrous collection of works of optical illusion by such well-known artists as Escher, Dali, and Arcimboldo, but also including Shigeo Fukuda’s incredible sculptures, and Rob Gonsalves’ realistic paintings. Scott Kim (whose work I first saw in Omni magazine in 1979) and his ambigrams, Ken Knowlton, Vik Muniz, Istvan Orosz, John Pugh, and Dick Termes are also among the 20 artists featured in this visual treat. The foreword was written by Douglas Hofstadter, which led me to…

Masters of Deception, compiled by Al Seckel, is a wondrous collection of works of optical illusion by such well-known artists as Escher, Dali, and Arcimboldo, but also including Shigeo Fukuda’s incredible sculptures, and Rob Gonsalves’ realistic paintings. Scott Kim (whose work I first saw in Omni magazine in 1979) and his ambigrams, Ken Knowlton, Vik Muniz, Istvan Orosz, John Pugh, and Dick Termes are also among the 20 artists featured in this visual treat. The foreword was written by Douglas Hofstadter, which led me to…

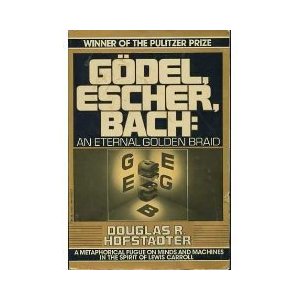

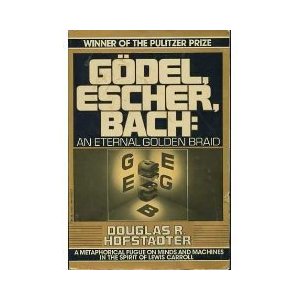

…Gödel, Escher, Bach, from which I first gained consciousness of the math in music, and of the music in math (math was something you do, not appreciate, even though I was quite good at “doing” it.) It’s been more than 25 years since I first discovered Hofstadter’s gem, and it occurred to me that I don’t recall finishing it…so that goes on the list; maybe sooner than later.

Ooh! There’s John Allen Paulos, and Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and Its Consequences – a fantastic book of concepts, although at times disjointed like many of his works (A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper, Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up, and more – all most excellent, if a little scattered). And Friedman's "The World is Flat"...

Hmm, Mark Tiedemann wrote a note on Heinlein recently (Robert A. Heinlein In Perspective)...but I only have six Heinlein books, and I promised myself I'd read Asimov's entire Foundation series from I, Robot to Foundation and Earth before I re-tried Heinlein. And I really do love Chalker, Farmer, Clarke, ...

…Gödel, Escher, Bach, from which I first gained consciousness of the math in music, and of the music in math (math was something you do, not appreciate, even though I was quite good at “doing” it.) It’s been more than 25 years since I first discovered Hofstadter’s gem, and it occurred to me that I don’t recall finishing it…so that goes on the list; maybe sooner than later.

Ooh! There’s John Allen Paulos, and Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and Its Consequences – a fantastic book of concepts, although at times disjointed like many of his works (A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper, Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up, and more – all most excellent, if a little scattered). And Friedman's "The World is Flat"...

Hmm, Mark Tiedemann wrote a note on Heinlein recently (Robert A. Heinlein In Perspective)...but I only have six Heinlein books, and I promised myself I'd read Asimov's entire Foundation series from I, Robot to Foundation and Earth before I re-tried Heinlein. And I really do love Chalker, Farmer, Clarke, ... ... and Jared Diamond, and Richard Dawkins, and Martin Gardner, and Stephen Hawking,...

...Michael Shermer, Bart Ehrmann, Uncle Cecil, Gary Larson...

No matter whether you get your education from electronic or print means, aural or visual, don't ever stop.

... and Jared Diamond, and Richard Dawkins, and Martin Gardner, and Stephen Hawking,...

...Michael Shermer, Bart Ehrmann, Uncle Cecil, Gary Larson...

No matter whether you get your education from electronic or print means, aural or visual, don't ever stop.