If you are interested in hearing well-considered podcasts putting religious claims under the microscope, here's a good source: Reasonable Doubts. The site is a labor of love by the following three individuals:

JEREMY BEAHAN is an Adjunct Professor teaching classes on: Philosophy, World Religions, Biblical Literature, Aesthetics, and Critical Thinking through FSU.

LUKE GALEN is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Grand Valley State University. He teaches classes on: the Psychology of Religion, Controversial Issues in Psychology, and Human Sexuality.

DAVID FLETCHER is the founder and former chair of CFI Aquinas College. He is an English and Speech teacher as well as an adjunct professor of Mythology.

What distinguishes this site from many other skeptic/freethinker sites is that the authors offer dozens of carefully-reasoned podcasts putting specific religious claims under the microscope. There is no ranting or bloviating here; the tone is academic and the presentations are clear. Listeners will come away with thorough understandings of the topics addressed:

What distinguishes us from many other skeptical podcasts is our special focus on counter-apologetics. We provide detailed counter-points to the fallacious logic and blatant misinformation used by religious apologists when attempting to discredit skepticism and provide rational arguments for their dogmas. We also defend the sufficiency of reason, science and naturalistic philosophies to provide a satisfactory and morally compelling understanding of the cosmos, human nature, art and culture.

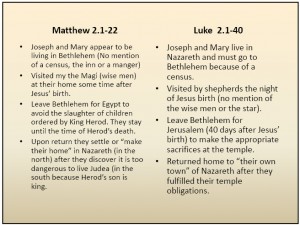

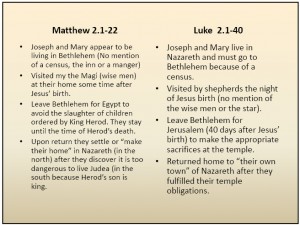

For example, in the podcast titled "Which Jesus?" (a presentation originally given at CFI), Jeremy Beahan discusses the many contradictions within the Gospel narratives. The lecture includes a powerpoint (see a sample slide below, setting out difference in the Christmas narrative):

I also listened to

a second podcast discussing Ernest Becker's work, leading to the modern theory of "terror management theory" (TMT) (this is

a topic that fascinates me). Becker's general idea is that we are

electric meat with large brains that can project into the future by generating "what if" hypotheticals. This makes us self-aware, but also tends to create a mind-body dualism riddled with anxiety--we deeply worry about death. Because we face our inexorable deaths, a paradox is created: we put lots of energy into denying death. We spin elaborate defenses through our symbolic systems (religion, capitalism, political). Becker argues that these defense symbols constitute buffers to our self-esteem, and we can only read self-esteem through our interactions with others. We latch onto group-based symbolic ideologies such as religions that offer simple steps to fend off death in order to enhance our self-esteem. All of our cultural strivings are to achieve a "heroic" feeling (even by serving a powerful Being, or by joining into warmongering) and a system of ready-made ethics for being a "hero" and "transcending death." Cultural striving = immortality striving. I was here and I

mattered. But any threat to these immortality strivings threaten believers. Therefore, being presented with a contrary world view (e.g., atheism) is inevitably threatening to our self-esteem and our mortality. Converting others to one's own world view is a way

to enhance one's own world view. If one can't convert others they still might be able to convince others to downplay their differences in public ((or even destroying others). About 20 years ago, many social scientists began testing these theories, with notable success (Judges reminded of their deaths set prostitution bond of $455; control judges--not reminded of their deaths--set bonds of $50). Reminders of death profoundly affect our behavior (e.g., 9/11 was a profound reminder of our impending deaths that dramatically kicked up our embrace of religion and patriotism--it urged people of all political persuasions to embrace others like themselves and to embrace more simplistic beliefs than before). Some of these experiments are described in this excellent lecture (I also described some of them

in my previous posts on "Terror Management Theory). Beahan highly recommended viewing a documentary exploring Becker's ideas: "

Flight From Death."

Here is the menu of podcasts currently offered by Reasonable Doubts. I highly recommend a visit.