Robert F. Kennedy’s Surrender Strategy for Beating Addiction

Atheists like me can enjoy uplifting religious messages like this one by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr:

Ressentiment Redux

Nietzsche, painted a vivid image of ressentiment that is applicable in modern times:

They monopolize virtue, these weak, hopelessly sick people, there is no doubt of it: "We alone are the good and just," they say, "we alone are homines bonae voluntatis.*" They walk among us as embodied reproaches, as warnings to us--as if health, well-constitutedness, strength, pride, and the sense of power were in themselves necessarily vicious things for which one must pay some day, and pay bitterly: how ready they themselves are at bottom to make one pay; how they crave to be hangmen. There is among them an abundance of the vengeful disguised as judges, who constantly bear the word "justice" in their mouths like poisonous spittle, always with pursed lips, always ready to spit upon all who are not discontented but go their way in good spirits. Nor is there lacking among them that most disgusting species of the vain, the mendacious failures whose aim is to appear as " beautiful souls" and who bring to market their deformed sensuality, wrapped up in verses and other swaddling clothes, as "purity of heart": the species of moral masturbators and "self-gratifiers." The will of the weak to represent some form of superiority, their instinct for devious paths to tyranny over the healthy--where can it not be discovered, this will to power of the weakest!

--Genealogy of Morals, Third Essay, Section 15 (1887)

Translation by Walter Kaufmann (1967)

*Men of good will

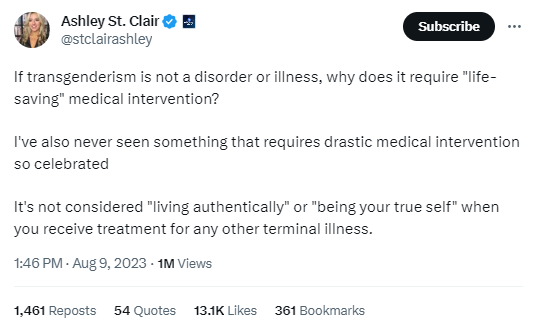

“What is Your Gender Identity?”

"What is Your Gender Identity?"

How would you respond to this question if you were put on the spot? Here's one approach . . .

If I were asked today, I would say something like this: "Unlike sex, "gender identity" is an incoherent and thus meaningless term."

Why do I think "gender identity" is an incoherent term? Here is one reason:

In other words, gender ideologists claim that one's genitals are both A) completely irrelevant to one's gender and B) highly relevant to one's gender. To make both of these claims is incoherent. Here's another thing I might add:

Another idea . . .

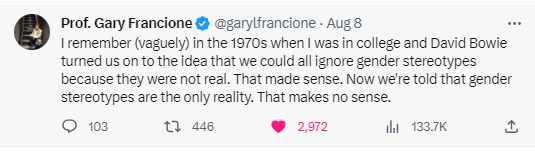

Perhaps you could point out that "gender ideology" embraces the regressive sex stereotypes most of us (not only feminists) have been trying to downplay for decades:

It really sucks to know that we worked so hard to erase gender stereotypes. Let girls and boys dress how they want, play with whatever toys they wanted, play whatever sports, have whatever interests...boys can dance, girls can be mechanics. We fought so hard. Then this crap.

Or you could invite them to listen to this podcast where Bari Weiss interviews Andrew Sullivan, a pioneer in gay rights. Sullivan doesn't support gender ideology because it is functionally homophobic. Most children claiming to be confused about their sex will, if left alone (not surgically butchered and rendered sterile by cross-sex hormones) grow up to accept their bodies, the great majority of them growing up to be gay (and see here). For this reason, Sullivan characterizes gender ideology to be homophobic.

If things heat up too much, you might want to inject some humor:

A Plea for Reconciliation

It's so amazing to watch these requests for reconciliation play out.

Many years ago, Frans de Waal recognized that apes reconcile with each other and he was ridiculed for making this observation. He was declared very wrong . . . until he was he was applauded for being right.

- Go to the previous page

- 1

- …

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- …

- 236

- Go to the next page