Democrats Increasingly Embrace Censorship to Maintain Unearned Power in the Class Warfare they are Waging

Leighton Woodhouse has articulated the connections between self-proclaimed Democrats, their love affair with censorship, authoritarianism and class-warfare in the latest post at Public:

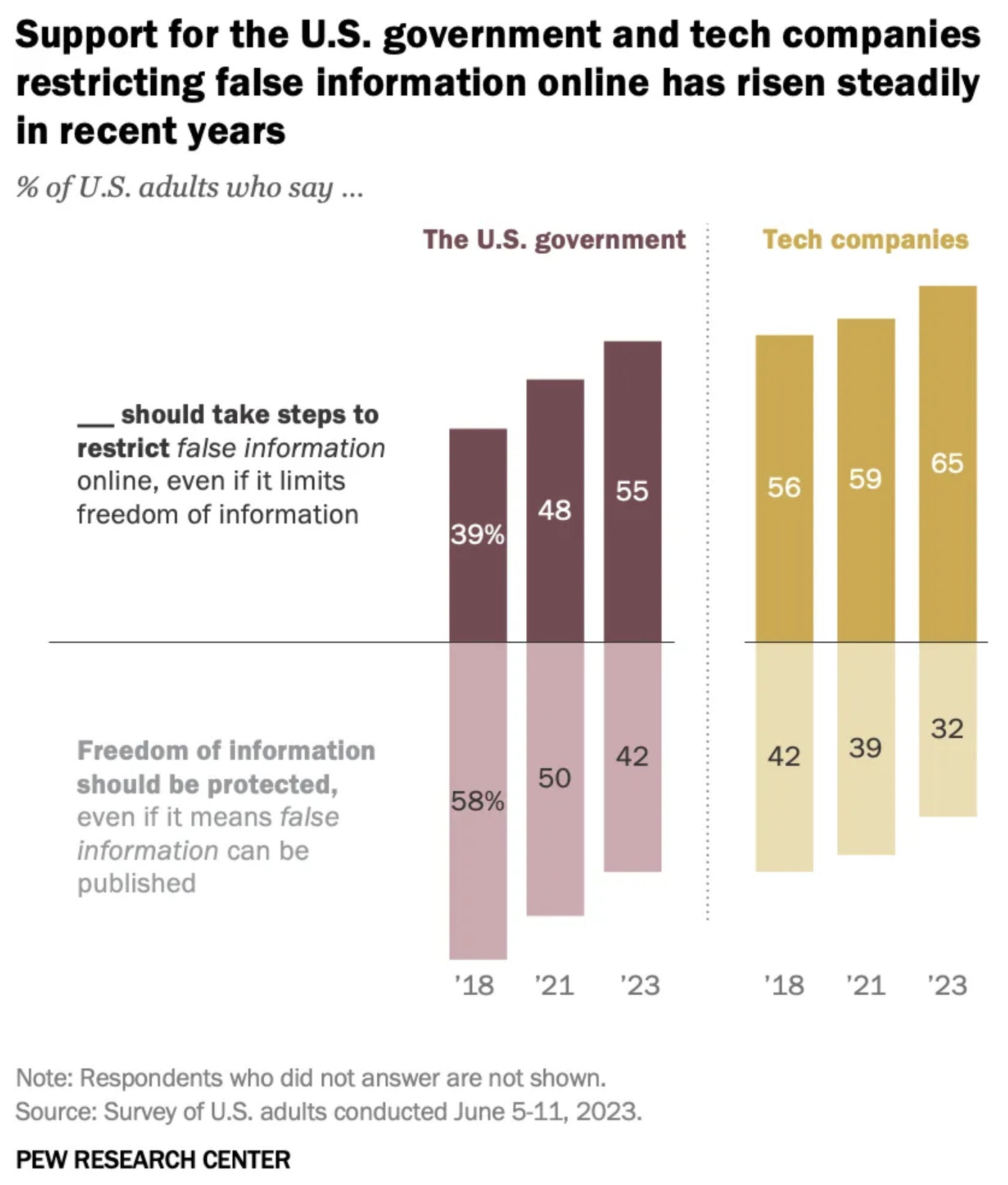

Pew has a poll out showing that Americans have become far less committed to free speech over the last five years. From 2018 to today, the percentage of Americans who favor tech companies and the US government “restricting false information online” has risen from 39% to 55%.The 16-point increase is almost entirely attributable to Democrats: while Republicans’ support for online speech restrictions has barely budged, Democrats’ support has gone from 40% to 70% in the span of half a decade. That’s a thirty-point shift against the First Amendment.

Since 2016, Democrats have heard almost nothing from their pundits and party leaders but constant fear-mongering about the wicked souls of their fellow citizens and how the internet is a weapon to spread their evil beliefs like the zombie fungus in The Last Of Us. Through Russiagate, Covid, and the aftermath of the January 6 “insurrection,” they have been terrorized by dark warnings of rising fascism, and told again and again and again that mere exposure to bad ideas is enough for unsuspecting persons to be transformed overnight, into deranged extremists and white supremacists capable of political violence.

Concurrent with that barrage of paranoid propaganda, the party’s base has shifted radically away from working class voters and toward college-educated white liberals. As the party has become beholden to urban, credentialed professionals, it has come to adopt the prejudices of that class. When today’s diehard Democrats cast their gazes upon the vast majority of the country, two-thirds of which does not have a bachelor’s degree, they see a nation of parochial bigots, each of them one Facebook post away from being brainwashed by QAnon.

These party loyalists believe they’re resisting fascism, but they’re courting it. Every authoritarian movement has started by persuading one faction of the population that another faction, be it a minority or a majority, is a malignant threat within the body politic. In the name of neutralizing that threat, the authoritarian party demands the abridgment of rights and liberties, beginning with political pluralism. And that starts with policing the opposition’s speech.

The Democratic Party is in a dark place. Still suffering under the illusion that it’s the party of workers, it is unable to see that its leaders and activists are waging a class war from above. Every time a Democratic leader intones gravely about “fascism,” they’re expressing the anxiety of a cloistered elite terrified of the resentments of the unwashed masses. Every time they invoke a crisis of democracy, they’re borrowing from the playbook of dictators, who always contrive a national emergency to justify their power grabs.

From this reactionary paranoia springs the Democratic rank-and-file’s turn against free speech and its leadership’s constant calls for online censorship. Capitulating to them is the road to ruin.

How desperate are things getting? Many of of our most sense-making institutions are substantially corrupted. Not only are they failing to do the work they were created to do, but their prime directive has become "Not Trump," all else being a matter of reverse engineering. If facts get in the way, fuck the facts.

Look at the pattern: in every major societal institution, from the news media and the universities to the FBI and DoD, powerful individuals are committing crimes, covering them up, and spreading disinformation.I sometimes feel like I'm in the crow's nest of the Titanic. I don't know whether to keep watching in horror or whether I should excuse myself to go down to the main deck to seek the distraction of the music.

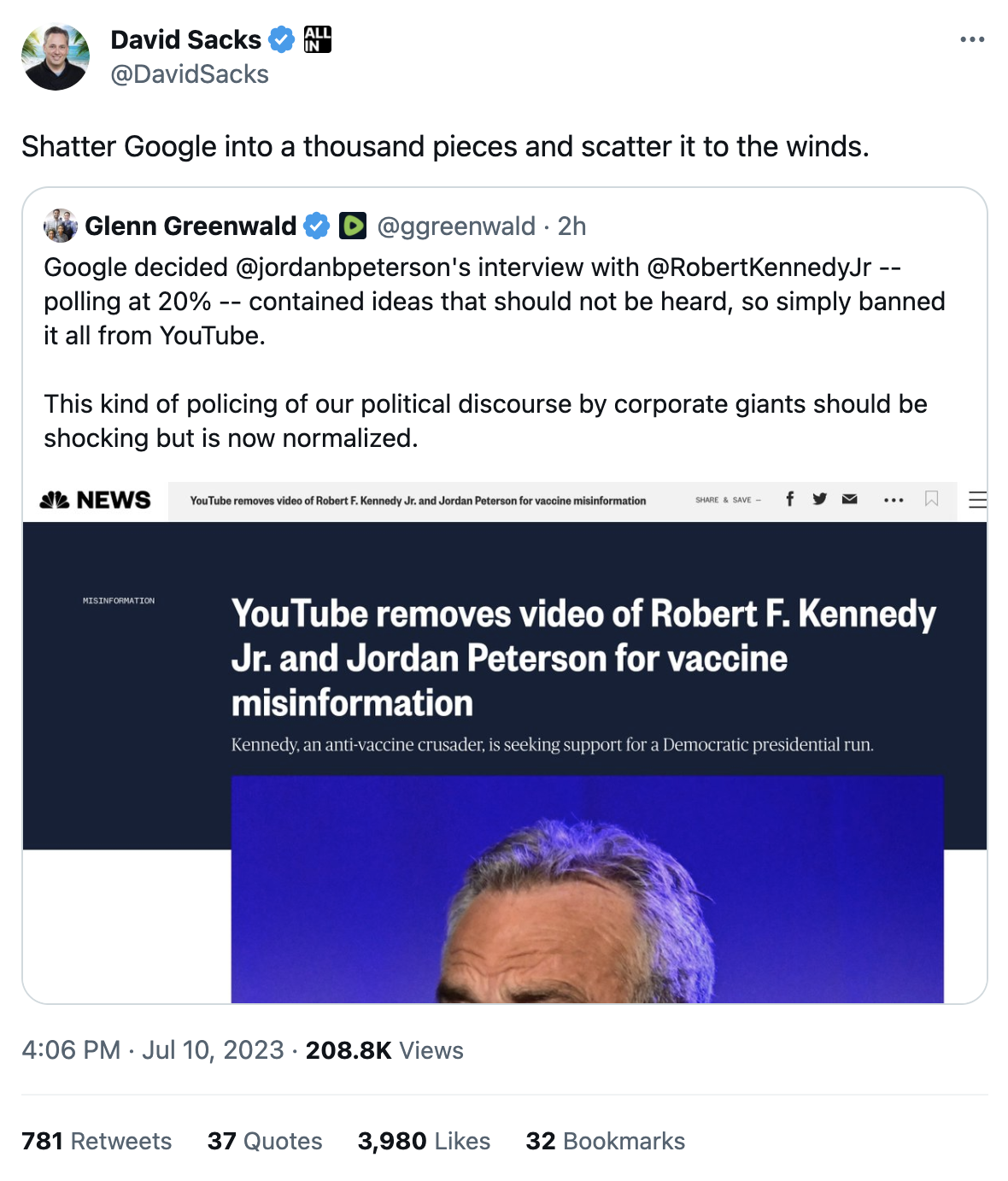

As soon as whistleblowers, journalists, or anyone else blows the whistle, the people in power cry “Conspiracy theory!” and demand their opponents be censored.

Which scandal are we referring to? Practically all of them.