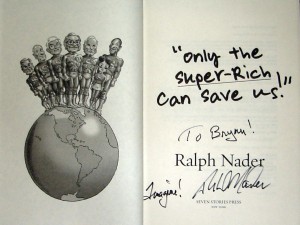

Tuesday afternoon, I was privileged to be able to attend a speech by Ralph Nader, followed by a question-and-answer session and a book-signing. He was promoting his new book, Only the Super-rich can save us! If you weren’t aware that he has a new book out, you aren’t alone. In fact, his presence in Omaha wasn’t well-publicized. I managed to see this article in the local paper which alerted me to both the fact that he had a new book out, and that he was in Omaha. I was fortunate enough to be able to arrange for some time off work, and went to the 3:00 session at McFoster’s Natural-Kind Cafe. Unfortunately, I completely forgot my role as a blogger and so I was woefully unprepared to take notes or photos. So rather than direct quotes, I’ll discuss some of the main themes of his speech, as well as the question-and-answer session.

Nader was scheduled to speak at 3:00 p.m., but didn’t actually take the podium until about 3:15, largely due to the enthusiastic crowd gathered around him peppering him with questions and having their books signed. He spoke for about a half-hour, then took questions for roughly another hour. I estimated the crowd to number about 80, and it was standing-room only in the small upstairs room at McFoster’s. His speech stuck pretty closely to the themes of the book, which asks us to re-imagine the last several years. The book begins with the disastrous fumbling of Hurricane Katrina, and a fictionalized Warren Buffet aghast at the apparent inability of a former first-world country to provide relief to its own citizens. Using his vast economic resources, he marshals the needed supplies and delivers them to a devastated New Orleans. The experience haunts him though, and he decides to convene a group of billionaires to solve some of the most pressing crises confronting American democracy. Using untold billions of their own, they are able to finally provide an effective foil against the big-money interests that would continue using the system to unjustly enrich themselves.

The Q&A session involved mostly friendly questioners asking his opinion on topics such as global warming, globalization, marijuana legalization and the proper role of technology in the classroom and in politics. He impressed the audience though, with his recall of one questioner in particular. She rose, gave her name and began to ask him about global warming, mentioning that she had asked him a similar question “maybe six or eight years ago in Lawrence, Kansas.” Nader corrected her, saying “No, it was 2000, it was during the 2000 campaign.” He provided several other details about their conversation from nine years ago, sufficient to prove that he really did remember the question. The questioner turned to the rest of the audience, her shock and pleasure at the recognition and Nader’s memory was plainly visible. Throughout, Nader gave the impression that he wouldn’t have minded answering questions all day, and appeared to genuinely relish the human contact and the engagement with the process.

One questioner asked him for his position on “medical cannabis”. Nader responded “You mean, medical marijuana? Nobody knows what cannabis is.” The response from the room plainly disproved that, but Nader went on to say that he was in favor of legalizing marijuana, emptying the jails of the low-level drug offenders (of which almost 850,000 were arrested last year for marijuana violations), then prosecuting corporate criminals and filling the jails with them instead. This drew an enthusiastic response from the crowd.

He explained that the average American is nowhere near as well off as the average European (all rhetoric aside). The citizenry of European democracies have universal health care, paid maternity leave, free tuition at the university level, and at least four weeks of vacation. A questioner asked about the level of taxation experienced to provide those benefits, and Nader conceded that the tax rates probably were higher, but not by much. He explained that by the time you include payroll taxes, FICA, sales taxes, etc… there was maybe a 10 percentage point gap between what the average American and the average European pays in taxes, but then went on to point out that you have to look at what they get for the money. Sure, taxes are higher, but Americans pay for all those other benefits out of their wages, or in lieu of wages. That is, the costs of a college education, (or health insurance, or medical care) are paid for out of wages, rather than out of taxes.

Nader expressed how difficult it was to get media attention. What was surprising was that the same difficulty was experienced with public television and radio stations. He relayed that he had been trying to get an interview with Terry Gross at NPR, but she was ducking his calls. One day, he got her on the phone by accident, and briefly asked her about appearing on her show, seeing as he was the presidential candidate (at the time) in third place, however distant. Her response was a snide “Well, you know, lots of people want to be on the show.” If you are so inclined, he would appreciate you contacting Terry Gross or Charlie Rose to encourage them to interview him.

He discussed how close America is to fascism, which Mussolini said “should more appropriately be called Corporatism because it is a merger of state and corporate power”. Nader quoted his father on the essential difference between socialism and capitalism:

Socialism is government ownership of the means of production. Capitalism is corporate ownership of the means of government.

Nader spoke often on the need for those whose interests are not being currently represented to organize, to mobilize and work at a grass-roots level. He urged them not to get frustrated and disaffected. He said something to the effect that there is plenty of time to be pessimistic once you’re dead, but for now, people need changes in this world. However, he plainly recognized money as vital to these efforts. More than vital– absolutely necessary, the lifeblood of any political movement in the U.S. And to me, that frank acknowledgment is the most disheartening thing of all. Nader essentially concedes that there is no way for either movements or independent political candidates to succeed without money on a massive scale. He used the analogy of starting a steel mill, saying that it would be madness to try and open a brand-new steel mill with only $300,000. It is a venture that would properly take several million to set up and operate– so too, in politics he argued that it’s futile to attempt to create change without funding on a similar scale. And here is where he gets to the meat of his book: it’s a unvarnished appeal for the wealthy to step up and buy social change.

He mentions that in the coming weeks, he expects to have up on the website his best estimates for what it would cost to purchase the votes necessary to implement social change. He mentioned single-payer health care might cost $2 billion or so, and some wealthy benefactor may decide to secure their legacy through purchasing health care for the nation, rather than starting a foundation or other similar enterprise. He explained that the wealthy had been behind many of the transformative struggles for social justice in American history, from wealthy Bostonians supporting the Abolition movement in its infancy to benefactors of the civil rights struggle.

I find myself conflicted as I reflect on the experience. On the one hand, it’s a crass acknowledgment that everything in this country is for sale, if only the price is right. This perspective utterly devalues the role that grass-roots movement can have in effecting social change. Nader would disagree, and say that change must be both top-down and bottom-up in order to be effective. He reflected on his long career, and mentioned that with each loss comes a series of “what-if” questions. “Would a different strategy have made all the difference?” “With a few more media buys in a given market have put us over the top?” He appears to have come to the conclusion that with access to massive amounts of cash, anything is possible in the political arena.

And that’s why I’m conflicted: despite my revulsion at this conclusion, I can’t really argue with it. It would also be much easier to dismiss this conclusion were it not coming from someone with as much credibility as Ralph Nader. He’s made it his life’s work to rectify some of the disparities that exist between corporate power and that of the common man. And a list of his accomplishments include some of the most valuable tools to that end that have ever been conceived: Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Consumer Product Safety Law, Freedom of Information Act(!), Whistleblower Protection Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and so on. But, he explained sadly, it would be impossible to replicate his career today– the system is too closed down. I’ve been reading Grand Illusion: the Myth of Voter Choice in a Two-Party Tyranny by Theresa Amato, Nader’s former campaign manager. This amazing book chronicles the massive structural and legal challenges that face a potential third-party candidate. It’s an eye-opening examination of the ways in which the system is tilted to the advantage of the two major parties, and the lengths to which they’ll go to ensure that advantage at every step.

Finally, it feels somewhat less than useless to depend on the very same billionaires who are profiting from the crisis to suddenly develop a social conscience and begin working for the common good rather than private gain. Especially given that income inequality levels recently reached all time-highs while poverty is also spiking. But Nader, the eternal optimist, invites us all to participate in “imaginative engagement” to help bring about a new type of new reality.

Brynn:

The most compelling and disturbing part of your post, for me, was the story about Terri Gross. We've simply GOT to get past the point where the major media outlets (including NPR) pre-ordain who is a "serious candidate" based on the amount of money they are piling up. We need clean (= publicly financed) elections.

Although NPR is far more serious in reporting news and presenting viewpoints than other American commercial networks. NPR often doesn't have the guts to call news the way it needs to be called. To compare, just watch Amy Goodman's DemocracyNow to see how it needs to be done. Too many well entrenched talking heads appear on NPR. Far too many, which is not surprising given the huge chunk of its budget that NPR takes in from big corporations. http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=NPR

Money = speech nowadays. It shouldn't and we should change the system to make sure that those without money can sit at the same table with the monied folks and to be considered for their viewpoints at election time. But that is all a distant fantasy.

Hence, Nader's conclusion that we need to super-rich to step in and save us.

Erich-

I couldn't agree more. I really enjoy all of the reporting done by Democracy Now, and I agree that they ought to serve as a model for others to follow. And in fact, Nader has had no problems getting interviews there (see here, here, and here).

And I think you've put your finger on the real issue, which is that money equals speech. Of course everyone has a theoretically equal right to free speech, but practically speaking, some people can buy more equality than others. How can you help but feel disheartened to realize that's the case? How does one begin to make changes to an entrenched, corrupt campaign finance system in which everyone benefits but people without money (and therefore without influence or even access)?

I forgot to mention that a real-life summit of the super-rich has already occurred. They met with the goal of curbing overpopulation, and a guest described it thusly:

They are solely focusing on overpopulation, not the democracy deficit in the US (as Nader would urge). Don't get me wrong, solving overpopulation would solve lots of other correlated problems. And I guess at least some people are now talking about it.

With all that big-brain, independent thinking these billionaires did, the best they could come up with was capping the population level by 2050 at 8.3 billion, instead of 9.3. At 8.3 billion, it's still a 26% increase from today's 6.7 billion. I hope that's aggressive enough.

I suppose that is why the wealthy have needed tax cuts, they couldn't afford to save us otherwise. Luckily the government won't save us now and we can depend on the charity of the wealthy and free market. You know, just like in 3rd world hell holes.

I'm tired.

I wish you would've told me that Nader was in town! I would've loved to go along!!