This is Chapter 26 of my advice to a hypothetical baby. And yes, what I’m really doing is acting out the time-travel fantasy of going back give myself some pointers on how to navigate life. If I only knew what I now know . . . All of these chapters (soon to be 100) can be found here.

You are only 26 days old, but you will someday escape your crib and your room with the same aplomb with which you escaped your mother’s womb. And at some point in your adventures as a bipedal ape, you might be lucky enough to see some fish. One thing that I always found amazing is how fast a fish can go from zero to some absurdly fast speed. It turns out that this was explained in Andy Clark’s excellent book, Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again (1998). I had the opportunity to take four graduate seminars with Andy at Washington University and he excelled at filled our heads with non-stop counter-intuitive observations and explaining them in clear English. Here’s how fish can take off like rockets:

The swimming capacities of many fishes, such as dolphins and bluefin tuna, are staggering. These aquatic beings far outperform anything that nautical science has so far produced. Such fish are both mavericks of maneuverability and, it seems, paradoxes of propulsion. It is estimated that the dolphin for example, is simply not strong enough l to propel itself at the speeds it is observed to reach. In attempting to unravel this mystery, two experts in fluid dynamics, the brothers Michael and George Triantafyllou, have been led ro an interesting hypothesis: that the extraordinary swimming efficiency of certain fishes is due to an evolved capacity to exploit and create additional sources of kinetic energy in the watery environment. Such fishes, it seems, exploit aquatic swirls, eddies, and vortices to ” rurbocharge” propulsion and aid maneuverability. Such fluid phenomena sometimes occur naturally (e.g., where flowing water hits a rock). But the fish’s exploitation of such external aids does not stop there. Instead, the fish actively creates a variety of vortices and pressure gradients (e.g. by flapping its tail) and then uses these to support subsequent speedy, agile behavior. By thus controlling and exploiting local environmental structure, the fish is able to produce fast starts and turns that make our ocean-going vessels look clumsy, ponderous, and laggardly. ” Aided by a continuous parade of such vortices,” Triantafyllou and Triantafyllou (1995, p. 69) point out,” it is even possible for a fish’s swimming efficiency to exceed 100 percent.” Ships and submarines reap no such benefits: they treat the aquatic environment as an obstacle to be negotiated and do not seek to subvert it to their own ends by monitoring and massaging the fluid dynamics surrounding the hull.

The tale of the tuna reminds us that biological systems profit profoundly from local environmental structure. The environment is not best conceived solely as a problem domain to be negotiated. It is equally, and crucially, a resource to be factored into the solutions. This simple observation has, as we have seen, some far-reaching consequences. First and foremost, we must recognize the brain for what it is. Ours are not the brains of disembodied spirits conveniently glued into ambulant, corporeal shells of flesh and blood. Rather, they are essentially the brains of embodied agents capable of creating and exploiting structure in the world.

This passage brings me to today’s advice: Don’t just “Do,” as Yoda suggests. Prepare your workspace and then “Do” with apparent super powers! Tuna prepare the nearby water by setting up their own currents before tapping into them. Ka-Bang! Reminds me of the acceleration technique of the cartoon Roadrunner, but tuna acceleration is not fiction.

You will have a choice about how well you do the things you choose to do in your life. You can be like many people out there, merely reacting to the world and getting by. Many people are fine with that. Other such people complain that they are victims of the world, helpless to take charge of their own lives. That was the complaint of Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, who complained that they were helpless to resist engaging in their illicit love affair because they were caught up in their passions. Dante was so utterly unconvinced by this explanation of innocence that he placed them in the Second Circle of Hell forever as a warning for the rest of us.

For many of us, we see the world as a big playroom (chapter 9), we want to be brave and we are ready to take charge of our lives. To choose this path and to engage in high quality life will require you to prepare and plan before doing, but this can take a hell of a lot of work. It’s often well worth it, though. In my life, almost every thing I’ve ever done of which I am proud, career or leisure, has taken years or decades of hard work. I discussed this back in chapter 9. The things I did earlier in my life often created my workspace for my future endeavors. I have tapped my present fish-tale into the eddies and vortices of my past achievements and learning experiences. I’m not claiming that my life has been well-planned. Far from it. I tend to jump into a lot of new things because they seem exciting and challenging (and because I am ADD-ish and a flow addict). I often jump into things because they are daunting and different than things I’ve ever done before. Once my past self commits me to a challenging situation, it is the job of my future self to figure a way out. Sometimes I don’t figure it out–that often happens–but it still has value as a learning experience. If I find myself struggling I might start feeling anxious, but the best cure for anxiety is hard work. This is my ebb and flow relationship with my world.

Whatever my next adventure, I want to be able to make use of what I’ve learned in the past. You’ll want that advantage too. When it comes to the moment of execution, you’ll want to have everything you need right there at your fingertips, ready to go. I think of that every time I sit down to work at my desk (see below). Lots of physical things, such as a pad of paper, pens, stapler and other office supplies. I also have two big screens to cut down on scrolling and hidden windows (a substantial efficiency boost). You might even see my talking pet hamster (on the left) in case I need some emotional support. You might see a rock under the right monitor – – I use that to hold up my phone for Facetime calls. I also have fast processor to run numerous incredible programs, programs that would have been hard to believe three decades ago, when I was already in the middle of my career as a lawyer. These are programs that I have configured just right to allow me to be the only employee of a full service law firm that is located in a corner of my bedroom. This same equipment also allows me to be a digital artist and musician.

Sometimes, I imagine time-transporting a king from the Middle Ages to see if he would ever want to go back. He might be content to type in “Here Ye” for the first few weeks . . .

I’m using the term “work space” more broadly than you might hear it elsewhere. What I mean is a physical setup combined with knowledge base such that when you want to get something done, you can get right to it. This is critically important for me, because of my impatience when it’s time to rock and roll. If I need to stop and start before going full speed, I get frustrated enough that I might never actually begin. I want my workspace to be a slippery slope: as soon as I step onto it, I want to be flying.

I always have five or ten projects in progress. I tap into them when I feel either inspired or ready to get to work. This brings to mind this quote by artist Chuck Close: “Amateurs look for inspiration. The rest of us just get up and go to work.” I see my many works-in-progress as workspaces for moving each of these projects to the next phase. I have thousands of ideas in my general collection at any time. I have hundreds of articles half-outlined, each of them in a computer folder that contains related articles, photos and anything else helpful. When I think of something that will further any of those articles, I quickly pull them out and add to the outline. When I talk about these computer folders, I’m describing the physical version of my thought process, but it is much more than that, because I truly off-load my thought-process into 0s and 1s. My memory could not possibly recall all of the information that I collect and periodically massage. What I’m describing is a great example of what Andy Clark referred to as the “extended self.” We often make the exterior works smart so that we don’t need to be. It’s not just the offloading of information either. My extended self includes the way I have organized my workspace and my numerous routines for interacting with all of this technology. If a natural disaster wiped out all of my data, I would feel like part of me died (that won’t happen because I keep meticulous off-site backups).

I think of my social network as another part of my workspace. This includes the people with whom I walk and talk periodically. There are about a dozen such people with whom I walk and talk and I do that 2 or 3 each week. I correspond with many other people throughout the week. We are friends, but we also help each other think. We form dynamic mini-sense-making “institutions” (see here for brief discussion of the work of economist Doug North based on his expansive notion of “institutions”). If a close friend of mine dies (and this has indeed happened), it feels like part of me died. That is because my “self” extends into the thought process of my closest friends and acquaintances (and vice-versa). I know this sounds impersonal but the people of my social network comprise part of my workspace (and I’m part of theirs).

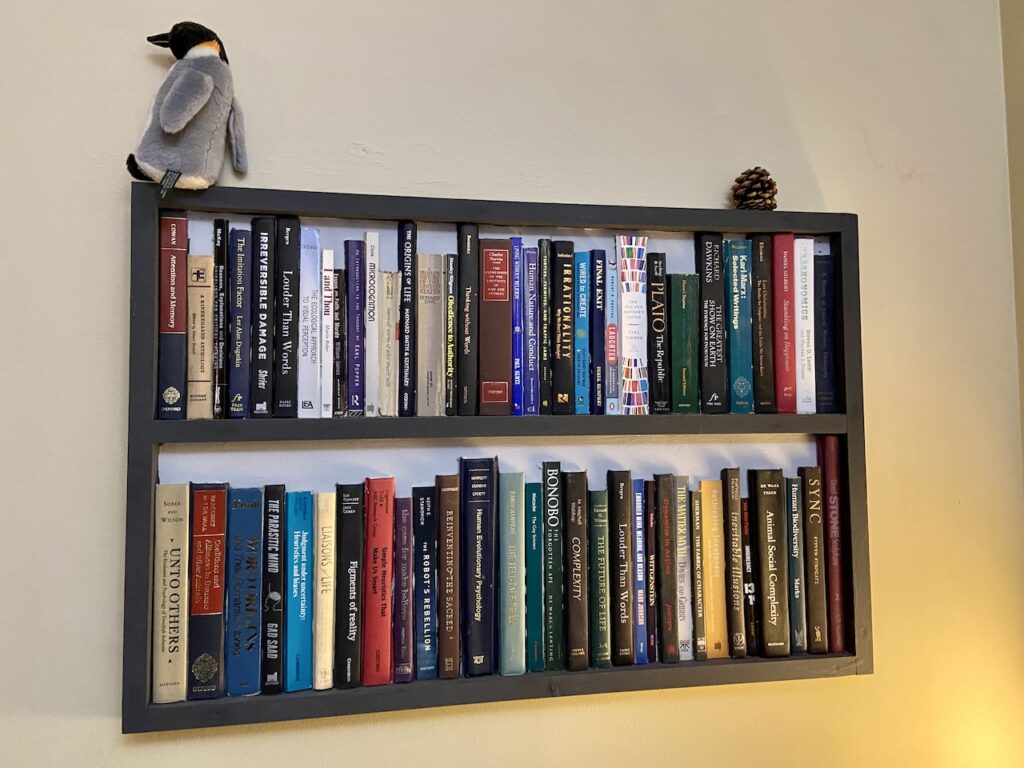

My workspace consists an immense amount of information accumulated over four decades of working as an attorney, musician and writer (and more recently, as a digital artist). There is no way to keep this information in my head, not even 1% of it. My challenge is thus to give good names to my files and organize them in tree structures that will make sense to the future version of me. I work hard to keep things organized in this manner. But there has been a lot of paper I needed to deal with. My secret weapon is my scanner, which has turned almost all of the paper coming into my life into readable pdfs. This includes thousands of science and philosophy (and many other topics) books that presented a huge problem, since they contained countless hand written notes, underlines and marginalia. For the past two years I have been busy cutting the spines off most of those books and running them through my scanner (I use Fujitsu’s excellent Scansnap scanner, which you can see behind my talking hamster, above). Most of my books are now readable pdfs available to me on all my devices through Dropbox. I can search them electronically, yet still read my hand written notes. This collection of scanned books, combined with scans of hundreds of magazine articles, is a huge part of my workspace. As for as the book spines, I have created two faux bookshelves using only the spines. I love the look of books, but I no longer need to deal with the paper.

BTW, I refuse to purchase books through Amazon’s Kindle option. I want to completely control my books. I want to be able to highlight, annotate and extract whatever I want. Nor do I want to give Amazon the power to flip a switch to deny me any of my books. Further, all of us are now seeing that big tech is getting extremely comfortable engaging in censorship, restricting information (including information later proven to be true) on a whim (with the sometimes-enthused support of the Democrat party–it is a distressing situation that I’ve often written on (and see here and here).

Whatever you do, if you love doing it and you want to do it well and often, you’ll want to set up a first class workspace. As I write this, I’m seeing considerable overlap between “workspace” and an expanded idea of “compounding,” the idea that our present abilities depends upon numerous skills we’ve accumulated over the years, starting at how to use a computer mouse, to understanding how a word processor works to using proofing tools, to learning how to post articles on websites. I also discuss compounding in Chapter 9 of this series.

What I’ve described above are a few of my passions in order to show the importance of my workspace, broadly defined. Your passions are probably completely different, but you’ll nevertheless want to consciously set up your own excellent workspace of skills, devices, resources and social contacts.

Having excellent workspaces to enhance efficiency is especially important if you have so many interests that you cannot get to all of them. That describes me. It also describes Nietzsche, who once wrote in The Gay Science #249:

Oh, my greed! There is no selfishness in my soul but only an all-coveting self that would like to appropriate many individuals as so many additional pairs of eyes and hands—a self that would like to bring back the whole past, too, and that will not lose anything that it could possibly possess. Oh, my greed is a flame! Oh, that I might be reborn in a hundred beings!” –Whoever does not know this sigh from firsthand experience does not know the passion of the search for knowledge.

This frustration of having too many passions and not enough hours is my definitely my plight, and it describes more than a few of my friends. If that is also true for you, it is even more important that you make good use of your 1,000 months (see Chapter 2) by setting up well-designed workspaces for each endeavor so that when you are ready to work, you will take off like a tuna.