I love libraries. More to the point, I love books. My wife also loves books, though now prefers her phone app to read when she gets the chance. I do read texts occasionally on my phone, and used to on my Palm, and I reluctantly read on/offline docs, but I prefer tradition.

I love libraries. More to the point, I love books. My wife also loves books, though now prefers her phone app to read when she gets the chance. I do read texts occasionally on my phone, and used to on my Palm, and I reluctantly read on/offline docs, but I prefer tradition.

There are many reasons for going to libraries. I rarely use them for research anymore. I only go for a specific book maybe 20% of the time. I delight in taking in the experience and seeing where it leads me. I might have an objective in mind, but there are so many opportunities awaiting me, it’s hard to choose just one, or two, or several!

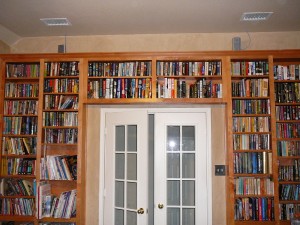

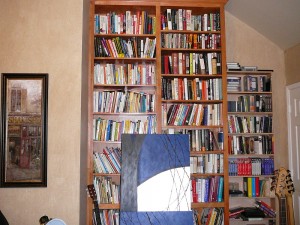

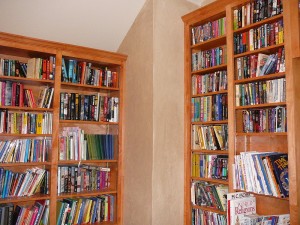

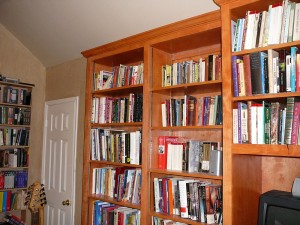

My own library  is not dissimilar from a public or university library in that respect, save perhaps its scale. That and it also serves as a music room (drum set, guitars, keyboard…) and an occasional media room. We have more than 5,300 books, though about 1,000 of them are for very young children (and mostly packed away now) and another 500 for young adults – combination homeschooling and love of books. I was putting books away the other night and looking for some references on homeschooling for a couple of pieces I am writing and went on a mini-adventure (every re-shelving trip up to my library results in armfuls coming back down with me)….

is not dissimilar from a public or university library in that respect, save perhaps its scale. That and it also serves as a music room (drum set, guitars, keyboard…) and an occasional media room. We have more than 5,300 books, though about 1,000 of them are for very young children (and mostly packed away now) and another 500 for young adults – combination homeschooling and love of books. I was putting books away the other night and looking for some references on homeschooling for a couple of pieces I am writing and went on a mini-adventure (every re-shelving trip up to my library results in armfuls coming back down with me)….

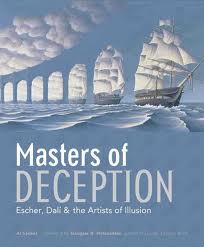

…I rediscovered  Masters of Deception, compiled by Al Seckel, is a wondrous collection of works of optical illusion by such well-known artists as Escher, Dali, and Arcimboldo, but also including Shigeo Fukuda’s incredible sculptures, and Rob Gonsalves’ realistic paintings. Scott Kim (whose work I first saw in Omni magazine in 1979) and his ambigrams, Ken Knowlton, Vik Muniz, Istvan Orosz, John Pugh, and Dick Termes are also among the 20 artists featured in this visual treat. The foreword was written by Douglas Hofstadter, which led me to…

Masters of Deception, compiled by Al Seckel, is a wondrous collection of works of optical illusion by such well-known artists as Escher, Dali, and Arcimboldo, but also including Shigeo Fukuda’s incredible sculptures, and Rob Gonsalves’ realistic paintings. Scott Kim (whose work I first saw in Omni magazine in 1979) and his ambigrams, Ken Knowlton, Vik Muniz, Istvan Orosz, John Pugh, and Dick Termes are also among the 20 artists featured in this visual treat. The foreword was written by Douglas Hofstadter, which led me to…

…Gödel, Escher, Bach, from which I first gained consciousness of the math in music, and of the music in math (math was something you do, not appreciate, even though I was quite good at “doing” it.) It’s been more than 25 years since I first discovered Hofstadter’s gem, and it occurred to me that I don’t recall finishing it…so that goes on the list; maybe sooner than later.

…Gödel, Escher, Bach, from which I first gained consciousness of the math in music, and of the music in math (math was something you do, not appreciate, even though I was quite good at “doing” it.) It’s been more than 25 years since I first discovered Hofstadter’s gem, and it occurred to me that I don’t recall finishing it…so that goes on the list; maybe sooner than later.

Ooh! There’s John Allen Paulos, and Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and Its Consequences – a fantastic book of concepts, although at times disjointed like many of his works (A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper, Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don’t Add Up, and more – all most excellent, if a little scattered). And Friedman’s “The World is Flat”…

Hmm, Mark Tiedemann wrote a note on Heinlein recently (Robert A. Heinlein In Perspective)…but I only have six Heinlein books, and I promised myself I’d read Asimov’s entire Foundation series from I, Robot to Foundation and Earth before I re-tried Heinlein. And I really do love Chalker, Farmer, Clarke, …

… and Jared Diamond, and Richard Dawkins, and Martin Gardner, and Stephen Hawking,…

…Michael Shermer, Bart Ehrmann, Uncle Cecil, Gary Larson…

No matter whether you get your education from electronic or print means, aural or visual, don’t ever stop.

Name-dropper. I, too, have Godel Escher Bach, Innumeracy, Shermer, Ehrman, et al.

I have 14 Heinleins on my hardcover shelf, another dozen in paperback, and pretty much the full run of Asimov from I, Robot on. I guesstimate we have about the same as you, closing on 6000 in house.

Neither of us have any electronic readers of any kind. We're talking about getting a Kindle or something similar (though a bookstore owner recently begged me not to publish via Kindle as Amazon is just destroying independent bookstores).

I have one shelf full of Oxford Companions, which as general references on specific topics I've found priceless. I also have two long shelves on the American Revolution and the Civil War, maybe 200 books in all…

I won't be doing any pictures of ours any time soon though, as my office is in chaos. But one of these days maybe.

Thanks for the post.

Ditto on Godel Escher Bach, Innumeracy, Shermer, Ehrman, et al. But my paltry collection is probably shy of 1,000 volumes, mostly paperback recreational reading.

I don't even have a complete Steven J Gould collection.

But unlike Mark, I am not a writer.

The pictures were strategically taken – there are more walls of books, but right now we have a treadmill, a temporary loft (Grandma is visiting and son #2 got bumped out of his guest room). Add shelves throughout the house and I need a bigger library. We were thrilled when we bought this house and saw the room for books. The shelves are all custom made, because we had 14 book cases in Korea and they weren't enough.

Turns out, neither were the ones we had made.

We went on a tear about eight years ago when I discovered that we had no "literature" for our homeschooled sons – just a few that were abridged. Fortunately, in addition to the internet, a bookstore in Seoul had a huge English section with many, many Oxford editions. Now we have a lot of books I'll probably never read. I'm not all that into "literature" – if I can't figure out why it is "literature", then it's not; I'm kind of funny that way. But, I'd rather have them than not. I'm kind of funny that way, too.

Thanks for sharing your library with us, Jim. If only I had 20 years to catch up on the books in my house. I have about 30 shelves of books at my house, about 60% of them read, but only about 30% of them read carefully. I also have a pile of about 40 books by the bed, on the floor. Each of them has a scrap of paper or a pen inside to serve as a bookmark.

When I read carefully, I create my own detailed table of contents in the blank pages preceding page 1, so that I can rapidly get back inside. I rely heavily on this technique when I write for DI. I would like to do this for every well-written book I own. I'm 54 years old, and It's becoming apparent that that quest is impossible.

Then there are the magazines pouring in every week and month. It's an incredible volume, much of which I won't get to ever, but I'm nonetheless supporting worthy publishers by subscribing.

I also keep my own ideas in the forms of outlines, ideas that I don't want to think about much, because I suspect that 1/3 of them are worth exploring in great detail, but I run out of time every day. Every damned day. Every incredible day. This brings to mind one of my most treasured quotes by Nietzsche (from The Gay Science, aphorism 249):

Peter Fuss, a man who once taught me philosophy in college once heard me whining that there are so many good books out there, yet I simply don't have the time to do more than scratch the surface. His advice was to take a deep breath, and then to choose wisely. He reminded me that when you pick up a book that "touches deeply," you are drawing on the ideas of hundreds of thinkers, all at the same time. You are reading one book, but that author is standing on the shoulders of giants. So I work hard to choose my books wisely. That advice gives me some respite, at least until I once again trip on that pile of books near the bed.

I also got some sage advice (from a librarian!) on the reading of books. I was bemoaning never being able to finish Paul Johnson's excellent "Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Eighties" (my copy; he updated in to include the Nineties) and a text the management class where I work was using. I wasn't in the class, and I thought most of the points made by the author were obvious, but I wanted to plow through because I don't like unfinished things – even if they take 20 years like Johnson's book. My friend said that at this point in his life, if he feels he's gotten enough out of a book, then he's done reading it and loses no sleep over not finishing. I use that approach on some, but not all of my projects.

And Erich, I sometimes use the back empty pages to add my own index of points I like and where to find them, so I guess I read "carefully" on occasion. Other times I flag the pages. Dennett's "Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon" is full of flags. I need to retire again someday to go through the stacks. I'm impressed that you've read 90% or your store – or 60%, depending on how the "read carefully" is interpreted (how many months have 28 days?). I think I'm closer to 30% right now. And with Half Price Books gift cards, the quantity increases geometrically while my reading runs linearly, even if in parallel at times.

Jim: I need to reiterate that I've only read (at all) 60% of my collection, and half of the books that I've read at all I haven't read carefully. This means that I haven't carefully read most of the books I currently own. And I should add that over the years I've given away hundreds of books that didn't pass the initial smell test.

I sometimes wonder how many hours a day I would read, if I could retire and all my other interests waned. I'd bet that I could easily read 5 hours every day, and I'd write another 5 hours. I suppose that I actually do this on my typical day, but by far most of my readings and writings are emails, legal filings and legal research at work.

I've known for a long time that I will likely never read all the books I own. Given that, owning them seems pointless. The trouble is, I also never know which ones I will read (or when), so divesting myself of them defeats the purpose of having them—keeping them nearby on the off chance that I'll pick one up.

I don't lose sleep over this anymore. Some time in the last four or five years I stopped fretting. I signed onto one of those online reading pages—Goodreads—and began adding in all the books I've ever read and the fact is, I don't remember at least 500 of them. My current total is over 2600, but I know that's short, and if I add in all the partials, the magazines, individual articles, etc, then my lifetime total to date is probably over 4000, mayb 4500.

And I don't remember over a third of them.

I do not reread. There are a handful of books I've read twice, maybe four or five more than that.

For a few years I did book reviews, which forced me to read books I would otherwise not have bothered with, and this provided some great pleasures.

But the fact is, for the dedicated reader, it is impossible to read everything worthwhile, never mind everything. So you can either stew in anxiety for all that you will miss or immerse yourself in what you can.

On FaceBook one of those lists has been going around, one I've seen in various forms for years, the 100 books the BBC thinks everyone should read but thinks most people have only read 6. The list has some remarkable books on it—Les Miserables, Of Mice and Men, Middelmarch, War & Peace, etc.—but also some "huh?" moments, not so much because the choice is bad but because there are better books by the same author. So while I could tick off 42 on the list, I could make a separate list of my own with over 200 that should have been on that list that I did read.

I read—many people read—for two purposes. The first is obvious, for information. I have a sizeable reference library, many of the books of which I would never recommend as "pleasurable" reading (Paul Johnson's "Modern Times" being an exception). But a lot of people who are not, by definition, Readers read for information. I've known many people who devour technical books and the like but would never think to pick up a novel or a book of essays or short stories. They do not read for the second, and in my opinion more important, reason.

I read to be more.

It's nebulous stated that way. What do I mean More? Those who have a lifetime of deep reading behind them understand. Reading enlarges our internal landscape, widens the horizons, gives us a sense of scope we would otherwise not have, matched possibly by the seasoned world traveler, the sort who picks up enough local language to function, and lives in a country long enough to dive into the parts not on the tour. By deep reading, my sense of my own Self has grown, and I apprehend more of the gestalt that is the world.

But also, the act of reading physically increases the connections in the brain, increases the brain's capacity, not in a specified way, but in such a way that the world is both less surprising and more amazing when we encounter new things.

So it ultimately doesn't matter how many books we end up getting through before we die. What matters is the attention, the exposure, the fact that we read, steadily and widely, and through that become more of ourselves than we would otherwise be. In this sense, each good book is a country we visit. Widely traveled is still widely traveled, even if we don't get to all of them, and what that makes of us is not diminished by those we didn't get to.

Mark: Thank you for your response to my comment. I'm trying to get to the point you describe. I'm intellectually there, but not emotionally. I keep thinking that there is, in those piles at my house, a great book that only if I would pick it up, would help me see the world in a brilliant new way. I say this from experience (and you would too). There are about a dozen books out there that profoundly shaped the way I think for the better. What if I had not worked extra hard to find them, and then to read them carefully–not just skimming–and let them soak in deeply? I figure that there are many others like those gems out there. If I only knew which ones they are . . .

I, of course, read for information and I also read to be more; the last 15 years have found me reading Johnson, Isaccson, Diamond, Friedman, and many more (I credit James Loewen's "Lies My Teacher Told Me" for sparking interests outside of the technical spectrum). But I also read to be entertained. Perhaps that is part of my "more".

I find little pleasure in what others call literature – I spend too much time critiquing or trying to figure out why it is considered such. I used to read science fiction and fantasy because I liked creativity in writing, and I don't see it in "regular" fiction (or literature). I still do infrequently – the "more" takes the majority of my reading time.

And I do re-read. Some books are adventures and if I enjoyed them the first time around, I'm sure I'll enjoy them again; generally from a different perspective of growing older. Dune, Tolkien, Farmer's Riverworld, Chalker's Well World, Simon Hawke, some of Joel Rosenberg (not Joel C.), some Piers Anthony, are worth re- and re-reads. To me.

I no longer have the partial eidetic memory of my teen years. If I haven't read a book in 20+ years, sometimes it's like reading it for the first time! (with an occasional "prescience" as I remember pieces of what's coming.) I also reread the nonfiction books that have influenced me. Perspective change again.

I absolutely love books. I wish I had such an extensive library that I might be able to hold all of the books that I own. Its funny, though. Like Erich, I have not read all of my books, and keep several on or near my bedside desk in the off chance that I will read one or another of them.

I think I like the thought that I have them, though. That knowledge is there at my disposal at my whim. Also, I could never really get into any of the "E-Books" unless I simply want to "try a book out." If I like it, though, I will undoubtedly buy it and put it on my shelf. Its almost as though my bookshelf serves as a trophy cabinet of sorts for me.

I also have GEB, though sadly my copy is worn and tarnished. Perhaps a sentimental quality, though, as it shows how much I enjoyed reading it. Though many of those near me know that the newest, crisp 20th anniversary edition is something I would absolutely LOVE for the Christmas. I'm hoping someone caught on by now, at least.

TheThinkingMan: I keep all those books by my bed because I am somewhat certain that you can learn through osmosis. Those ideas somehow ooze out of those books, especially in the middle of the night, and slip into your mind (it might be through the ears, or maybe the nostrils).

Erich,

If only it were that simple, I would never need to study.

Now if only we could develop some sort of sleep-reader. No one take that idea, its mine!

Learning in one's sleep is an old Skiffy idea. But I suspect it would be much like food pills—sure, you'd wake up with all that stuff in your head, but how much fun would that be?

Also, there is something to the whole notion of associational smarts—I've felt smarter just buying certain books and carrying them around.

The best books that I've found; the gems that can change your brain and turbo-boost your evolution:

1. Tom Robbins novels (all of 'em)

2. Robert Anton Wilson (his non-fiction)

3. Timothy Leary ('Politics of Ecstasy', 'Chaos and Cyberculture', 'Your Brain is God')

4. Terence McKenna ('The Archaic Revival', 'Food of the Gods')

Something on reading lists:

http://marktiedemann.com/wordpress/?p=393

Mark: Thanks for the rec of Rite of Passage. I just ordered a copy for my 12-year old daughter, who also happens to love stories about starships.

Crap. More books to add to "the list". Thanks, guys!

Eh-hem . . . Jim, you started this topic . . .

I just finished reading the revised and expanded edition of Michael Shermer's "Why People Shouldn't Believe Things I Think Are Weird"… um, I mean "Why People Believe Weird Things". Shermer is an ex-Theology student and born-again Christian, who has been born-once-again as an agnostic and professional skeptic–which is the niche he currently resides in. When I first brought this book home I honestly thought I was in for the literary equivalent of cold, plain oatmeal–probably healthy, but dull and flavorless and hard to swallow. My bias was swiftly reinforced after reading the awful Foreword in which Paleontologist/Evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould awkwardly tries to defend "debunking", aka skepticism. Three scattershot pages filled with odd generalizations infused with misplaced certitudes such as, "Consciousness, vouchsafed only to our species in the history of life on earth, is the most god-awfully potent evolutionary invention ever developed.". I hope Gould meant this sentence as deep satire, or a sly nudge 'n wink insider joke, otherwise it comes across as complete nonsense. First of all, consciousness remains a deep mystery, and as a field of study is still in it's infancy. The indwelling consciousness of animals (and even plants) remains indeterminate–neither proven or disproven. Secondly, to use the term "god-awfully" as Gould does seems ironic at best, coming from a man who does not believe in gods. Finally, the contradictions seen in a "development" of an "evolutionary invention" stands in the muck of it's own absurdity, and needs no further comment. Then Gould goes on to declare that irrationality and romanticism results inevitably in "mob action." Gould ends this mess with his belief that "rationality itself, tied to moral decency" are the "only two escapes" for humankind. Moral decency, huh? Based on what, exactly? Sounds like the blunt moral club used by fundamentalist religions worldwide, and stinks of the Taliban, the Inquisition, and the Third Reich. Ugh.

However, after one of the worst possible starts, as soon as I plunged into the actual Shermer text I was pleasantly shocked. Hmm, this stuff seems insightful, entertaining, witty and loaded with sharp reason. I really liked this book… a lot. Shermer appears to be a truly open-minded skeptic, able to look at a "weird" subject from all angles, but always operating under the floodlight of reason and hard science. What's this? A skeptic who says "there is psychological evidence that magical thinking reduces anxiety"? Shermer also believes there is medical evidence that prayer and meditation may lead to greater physical and mental health, as well as "anthropological evidence that magicians, shamans, and the kings who use them, have more power…".

Wow- unexpected and brave statements coming from a Director of the Skeptics Society.

One of my few minor criticisms of this book is the way Shermer uses Gallup and other poll's to bolster his contention that large percentages of people believe "nonsense of all sorts" and saying the results are "alarming" to him. A poll showing 19% of adult Americans believing in witches? The only "alarming" thing I see here is that the number isn't up in the high 90%. Witches obviously do exist. The Priests and Priestesses of the Wiccan religion are called witches, and they perform rituals within a coven filled with other witches. They are real people, found in the real world. I wonder if the poll that Shermer cited qualified witches as women flying around on brooms, or a hags with talking cats? Doubt it. And what about belief in UFO's that Shermer is so worried about? I'm certain that UFO's exist. I see them all the time. Quite often I'll look in the sky and spot something up there that I can't positively identify. Was that a bird or a bat? Is that a plane or a …? Well, it's an unidentified flying object isn't it? I've never, however, observed a spacecraft piloted by an extra-terrestrial entity. And 35% of people believing in ghosts? But what do you mean by 'ghost'? My dead great grandfather's hovering form, or a feeling of negative energy in the house? My point being we need to operationally define these terms to get a true and meaningful result, and I'm surprised that a professional skeptic like Shermer would overlook this.

After this small bump in the road the book zips along, offering up chapter after chapter of great stuff. Shermer confronts and deflates the Ayn Rand cult, exposes psychic frauds, and drills deep into the alien abduction phenomenon (simply a zany manifestation of pop culture?). The best chunks for me were Shermer's relentless evisceration of creationists and Holocaust revisionists. First he brilliantly lumps the two nut groups together, and then proceeds to pounds them into a pulp before escorting them off the stage of plausibility. Using bullet points, cold logic and facts, Shermer effectively dismembers each claim or stance, dismantles their already shaky foundations, and simply removes the creationists and Holocaust revisionists from the menu. In my opinion he closes the book on the creationist and revisionist proponents, and exposes them as the walking talking human errors they are. Devastating assault, and a great victory for science and logic.

"Why People Believe Weird Things" goes off the boil a bit towards the end, and limps to a rather fuzzy completion with this final, unfortunate and nearly incomprehensible sentence, "In other words, the belief in UFO's and alien abductions, like that of other weird beliefs, is orthogonal to and independent of the evidence for or against it, or the intelligence of its proponents, which makes my point. Q.E.D."

Huh? Yes, he actually ended his book with this. Here's what I think Shermer should have ended with, succeeding with great elegance to say what S.J. Gould failed to: "It is a different source of hope, but it is hope nonetheless: hope that human intelligence, combined with compassion, can solve our myriad problems and enhance the quality of each life; hope that historical progress continues on its march toward greater freedoms and acceptance for all humans; and hope that reason and science as well as love and empathy can help us understand our universe, our world, and ourselves."

Bravo Mr. Shermer.

I do like Shermer's stuff, but everything I've read seems too soft and inviting a "maybe" (even Why Darwin Matters), which takes some of the shine off for me. Still, he's very thorough. I think he prefers to present evidence in more of a "we report, you decide" manner. But I think he reserves his more biting criticisms; he always comes off as so calm and composed – and rational – in his interviews and debates.

And that Q.E.D. came at the end of the chapter "Why Smart People Believe Weird Things" – independent of the intelligence of the proponents. Humans are wired to believe (see Dennett and Boyer.)

Well, most are.

Funny, that. I love 'Maybe'. I'm also a big fan of 'it depends', 'we'll see', I'm not sure' and 'I don't know'. For me, uncertainty and indeterminacy = shine on; certainty and determinacy = shine off. Usually.

Also, I'm 1/4 of the way through Shermer's "Science Friction" – Yawn…Zzzz. Looks to be a big step down in quality from his "WPBWT". Disjointed too…seems like Shermer just dumped out his file cabinet and then scooped it all together to assemble between two covers. Disappointed so far.