Summary: A chilling portrait of everyday life in the world’s most fanatically totalitarian state.

When the Cold War ended, communism came tumbling down worldwide. The Soviet Union disintegrated, the Warsaw Pact nations joined the West, and though China’s authoritarian government still stands, its economy has become capitalist in all but name. But one true communist state still exists, defiant in its isolation, sealed off from the outside world by almost impenetrable barriers. That state is North Korea, the topic of Barbara Demick’s superb book Nothing to Envy. By interviewing some of the few who’ve successfully escaped, Demick weaves a frighteningly compelling narrative of what everyday life is like in the world’s most brutal and reclusive dictatorship.

Isolated from the outside world, North Korea has developed into a cult of personality rivaling anything found in the most fanatical religion. Its first president, Kim Il-sung, and his son and successor Kim Jong-il aren’t just the absolute rulers of the country, they’re hailed as divine saviors, literally able to perform miracles:

Broadcasters would speak of Kim Il-sung or Kim Jong-il breathlessly, in the manner of Pentecostal preachers. North Korean newspapers carried tales of supernatural phenomena. Stormy seas were said to be calmed when sailors clinging to a sinking ship sang songs in praise of Kim Il-sung. When Kim Jong-il went to the DMZ, a mysterious fog descended to protect him from lurking South Korean snipers. He caused trees to bloom and snow to melt. If Kim Il-sung was God, then Kim Jong-il was the son of God. Like Jesus Christ, Kim Jong-il’s birth was said to have been heralded by a radiant star in the sky and the appearance of a beautiful double rainbow. A swallow descended from heaven to sing of the birth of a “general who will rule the world.” [p.45]

Ludicrous stories like these are drilled into every North Korean citizen from birth through state-run schools and propaganda outlets. Children don’t celebrate their own birthdays, but those of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il. Even though Kim Il-sung has been dead for years, he’s still officially the president (which has led Christopher Hitchens to call North Korea a “thanatocracy”), ruling the country in spirit from his mausoleum beneath a massive obelisk officially named the “Tower of Eternal Life” [p.122].

Demick also details how every North Korean is expected to wear lapel pins of Kim Il-sung, as well as display portraits of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il on their house’s walls which they must keep scrupulously clean [p.46]. TV sets and radios, for the rare few that have them, have their dials welded so they can only be tuned to the country’s official propaganda stations. State secret police rigorously enforce these laws, as do community organizations called inminban which require neighbors to spy on each other. The penalty for almost any offense is either lifetime imprisonment in a gulag or death.

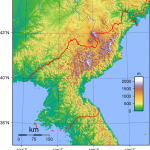

Meanwhile, as North Korea’s leaders sing their own praises, the country is in a state of slow disintegration. The planned economy is almost completely moribund. Except for Pyongyang, North Korea no longer has electricity. (The book opens with a striking satellite photograph of the Korean peninsula at night – the South is ablaze with light, while the North is a dark void.) Its industries have ceased functioning, and workers at state-run businesses are rarely if ever paid. Its hospitals don’t have even simple supplies like bandages, antibiotics, or IV bags. Most of its factories and infrastructure have been stripped by scavengers who steal wire and machine parts to sell for scrap. More incredibly, North Korea doesn’t even produce enough food to feed itself. During a terrible famine in the 1990s, it’s estimated that over two million people died, and the survivors, many of them orphans, were reduced to eating ground-up corn husks, leaves, grass, and tree bark. Most state-owned farms have been abandoned while people tend tiny, illegal private gardens. To this day, North Koreans are chronically malnourished, and an entire generation is growing up physically and mentally stunted. In the early 1990s, according to Demick, the army had to lower its five-foot-three minimum height requirement because most recruits didn’t meet it [p.188].

Only two things have prevented North Korea from collapsing. One is that, despite its stated principle of Juche, or self-reliance, the country is propped up by food and fuel aid from China, which is seeking to prevent a massive refugee crisis on its border. The other is the black markets which have sprung up in many towns and villages, enabling North Koreans to buy, sell and trade food and goods that the country doesn’t produce. Technically these spontaneous outbreaks of capitalism are illegal, but for the most part, the government ignores them.

Demick draws these details from interviews with defectors, most of whom have escaped over the lightly guarded northern border into China and from there to South Korea. Their stories, retold as first-person accounts, form a gripping narrative that makes this book read like a fast-paced novel rather than a work of nonfiction. It also emphasizes the humanity of the North Koreans – brainwashed though many of them are, they’re still ordinary people living under the shadow of almost unimaginable totalitarianism. The vividness of their stories gave me a strong feeling of compassion for them, even as it made me despair for their future, because Demick takes pains to show that there are no easy solutions to this dilemma.

Even if North Korea ultimately dissolves peacefully, rather than launching a suicidal war on its neighbors, there will be over twenty-five million people living in utter poverty and lacking any knowledge of how to survive in a modern, industrialized democracy. Reintegrating them into the outside world will be a staggering task. Even some of the defectors, the people most motivated to seek freedom and a better life for themselves, have had difficulty with it. I don’t know what the ultimate solution will be, but Barbara Demick has done a superb job of clearly outlining the scope of the problem.

I know you don't control the advertisements here, so I'll just chuckle quietly to myself about seeing an ad for Scientology next to a review of a book about the North Korean state cult.

I don't think that North Korea's centralized planned economic model fits within most definitions of communism. It is more or less a perversion of communism that is closer to the totalitarism described in "1984"