A few weeks ago I ate dinner with friends. One of the friends mentioned that, a few weeks earlier, he had attended a party in an upscale neighborhood. At that party, one of the guests announced that she had brought her own bottle of wine because the host’s expensive wine wasn’t good enough.

From my end of the table, I blurted out that it is not necessary to have expensive wine to have a meaningful gathering with friends or family. In fact, I added, “wine is not necessary at all.”

I was about to elaborate when I noticed that the other adults at the table were staring at me like I had three eyes. “That’s not correct,” they told me, almost in unison.

I know that “look” well. I have received that same “look” from various people on other occasions. On one occasion I got “the look” from someone who was trying to justify that an ordinary car wasn’t sufficient, so he needed to buy a BMW. Another person who gave me “the look” was trying to convince me that her $75,000 kitchen remodeling was “necessary,” even though all of the appliances in her existing kitchen functioned perfectly. The problem with her current kitchen was that it was “old.”

I have also received that same look from fundamentalists when I explain that the earth is billions of years old. The “look” is a “we-will-pretend-you-didn’t-say-that” look. It shouldn’t surprise me to draw the same “look” from both consumers and Believers, given that wasteful and pretentious spending is the de facto national religion of the United States. We’ve moralized extravagant spending to such an extent that “living the good life” means buying lots of things we don’t really need.

Back to that dinner I was attending, the conversation moved on, but not my intrigue at the discussion about the “necessity” of expensive wine.

You know, all I had done was to state an undeniably true fact: People don’t really need to drink wine (certainly not expensive wine) to have meaningful social gatherings. After all, poor people can’t afford expensive wine. Are poor people incapable of having meaningful gatherings because they can’t afford expensive wine? Raise your elitist hand if you believe that.

Nonetheless, in making my pronouncement about wine at dinner, I had appeared boorish to my acquaintances. But I felt innocent. How could it possibly be that consuming particular types of food could, in any sense, be essential?

Here’s a rule of thumb I follow: Whenever something doesn’t make any sense to me (in this case, that a particular expensive food is a prerequisite for having meaningful social gatherings), it’s best to assume that relationships are somehow being threatened. When a claim makes no sense, it’s always about relationships, not the things that appear to be the topic (here, expensive wine).

I also receive this “look” whenever I disclose that I cut my hair with a Flowbee, a hair-cutting device that works in tandem with your household vacuum cleaner (don’t laugh unless you’ve tried it). The Flowbee works especially well on men’s hair styles. Acquaintances to whom I mention this usually laugh, then protest that I really should spend $20 every six weeks to get professional haircuts. I “deserve” this, they tell me. What’s curious is that no one claims (after looking at my hair) that the hokey-seeming Flowbee doesn’t look like a haircut done by someone at a styling salon. At bottom, their discomfort is about the social propriety of using a Flowbee, not about the function of the device. They, too, would like good haircuts and they, too, would like to save LOTS of money, but they wouldn’t dare use a Flowbee.

America would not be American without consumerist excess, would it? Consider the $1,200 car sound systems that people “must have.” Consider designer bed sheets stores where you can get a twin sized Praga Embroidered Duvet Cover for only $540. And don’t forget that caring America parents “deserve” to spend $140 for designer diaper bags for their peeing and pooping babies.

Consider, also, $2,000 designer watches. My young daughters have $10 watches that keep good time, so paying $2,000 couldn’t possibly be about knowing the time. It’s hard for me to believe that it’s about looking beautiful, either. I have trouble thinking that people who flash affluence on their wrists are beautiful, especially when dollars are fungible. That needlessly spent $1990 could have dramatically improved the lives of numerous desperate children. Please tell me where my logic has gone awry!

But I seem to be drifting off topic. My question is why (why? WHY?) do we so often spend big money on things that appear to be primarily non-functional?

Here’s one place to start. We gullibly allow the high cost of an item to serve as a token for quality, even when a price is jacked up to obscene levels. Guitars are a good example. I’ve played the guitar for four decades, often with bands. I’m picky about the guitars I play. They need to play well and sound good. You can buy a brand new terrific-sounding guitar for less than $2,000 (sometimes much less), but many people insist on paying much more. That extra money they spend almost always buys them decorations rather than improved function (they often kid themselves otherwise). Admittedly, exorbitant prices might give them improved sound or playability, but that improvement (if there is any) is minimal. The people who buy really expensive guitars usually spend more time bragging about the rare wood and pearl inlays than they do playing their guitars. Consider this: What kind of musician that would need to own the Martin D-45 Dreadnought Acoustic Guitar for $6,999.99:

The most ornately appointed guitar in the Martin line. The D-45 Dreadnought Acoustic Guitar has over 900 individual pieces of abalone inlaid into the bindings of the top, sides, back, and rosette. Large C.F. Martin abalone letters adorn the headstock; abalone hexagon inlays are used as position markers on the bound ebony fingerboard. Solid spruce top and traditional Martin bracing pattern generates fantastic tone. Features rich solid rosewood sides and 2-piece back.

Notice the large number of non-functional abalone inlays that extra money buys! With guitars, you can pay a lot more than necessary without receiving any increased functionality. It’s the same thing with virtually every other type of product offered for sale in America, including sound systems, dinnerware, light fixtures, bicycles, toasters, luggage, sports equipment and even caskets. Virtually anything that you might use in public is offered in an expensive “gold-plated” version.

And we mustn’t forget about the world of clothing, where functionality is often barely considered. If you bought a great outfit at K-Mart, you might sit silently while your acquaintances brag that they got their outfits at specialty shops where they paid five times as much. Here’s why you don’t brag about being thrifty: While you’d be showing your acumen as a shopper, you’d be admitting that cost matters to you. Not cool.

Food is my favorite luxury item to pick on because, over the past few decades, we’ve raised the bar incredibly high as to what kind of food is socially acceptable. Executives insist in holding power lunches at high-priced restaurants where waiters dote upon them. It embarrasses most of them to hold lunch meetings at reasonably priced restaurants, because doing this would be an admission that price is a consideration. And what about all the people for whom eating gourmet food (often euphemistically called “good food”) needs to be a daily occurrence? Isn’t it clear that eating gourmet food is not primarily about nutrition? Yes, it’s about exciting tastes, but often not (just watch the people who eat most expensive food. Are they really paying attention to the tastes?). Again, it’s about showing other people what you can afford to eat. The irony is that, in the privacy of their own homes, many of these same people happily eat cheaper foods they wouldn’t dare get near in public. And after eating regular food in the privacy of their homes, they don’t vomit. They don’t die. As long as no one peeks in their window and sees them doing it!

We often don’t notice our strange ways of life, including our constant need to buy things that we don’t need. Somehow, we get used to our way of life. Over time, our wants morph into needs slowly, so we don’t notice. One way to see how bizarre our lavish consumer spending has become is to travel away from it all for at least a few weeks. Far away. Go to a place where people eat plain food and live in plain houses. On several times, I’ve come home after extended trips to several places that were very much unlike America in terms of consumer glut (Ecuador, Guatemala and China)—the re-entry to America is always shocking. Mindy Carney has written eloquently about the phenomenon of coming back “home.” Nietzsche summed up the need to leave home in order to know who you are:

When taking leave is needed.– From what you would know and measure, you must take leave, at least for a time. Only after having left town, you see how high its towers rise above the houses.

[from Wanderer and his Shadow]

Americans constantly yak about all of those “essential” things out there. iPods are now “essential” for many people, as though it’s essential to always have access to great-sounding music. Most “essential” things are not really essential, though. If they were, we’d be screaming to our politicians that everyone should have all of those “essential” things. That’s the paradox about modern “essential” things. You see, there’s a new definition of “essential.” When Americans claim that their purchases are “essential,” they are almost always talking about their wants, not true needs.

It’s the same story with all of the many other “essential” designer products and services we simply “must” have. I dare anyone who denies that they own a lot of things whose primary purpose is to socially display them to invite me to visit his or her home. I’ll slap “non-essential” post-it notes on most of that essential stuff they own. I’m not trying act like I’m above it all. I’m guilty too. It pisses me off that I so often fall prey to the marketers. That’s why I’ve written on this topics before (here, here and here), and now again.

We work long hours to afford all of those items we crave. But we crave them primarily to display them. And we work so hard to buy them that we fail to spend the time doing those things we claim to be much more important, such things as spending quality time with our friends and families. And participating to make our communities better places to live.

Again, why would so many otherwise intelligent people fall into such bizarre, expensive and often self-destructive habits? Why can’t we seem to get beyond our cravings to possess and display fancy things? This strange behavior is so powerful that it currently drives much of our economy. It’s a buy and brag mentality. The thought of bragging—displaying our purchases to others–drives the sales. Imagine the droves of stores that would go out of business if we enforced a law that outlawed bragging about the non-essential things we bought!

We never stop sizing each other up. Since it’s not possible to directly ascertain Darwinian fitness, we do it indirectly by checking out other peoples’ collections of consumer goods. We allow expensive consumer possessions serve as tokens for Darwinian fitness. We are content to figure out who is who based on what they own. We consider people who have easy access to goods and services to be more attractive. Just think back to your childhood. Most of us checked out our playmates’ collections of toys to determine who the cool kids were. We haven’t come very far as adults, have we?

Is there anyone out there who can explain this national obsession to spend? Almost no one. Rarely does any writer try to offer a deeply-rooted framework to help us analyze our compulsions to (apparently) waste our money on designer products. Even if someone could explain it to us, most of us would probably be too busy shopping to pay any attention to them. Further, it would is highly unlikely to see this topic addressed on the mass media. After all, if the topic were addressed well, it would hurt the sponsors of any such article or show. Financial suicide.

Admittedly, quite a few people have written about rampant consumerism. Juliet Schor’s book, for example, The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need (1998), is rich with anecdotes and statistics. Schor, however, never fully addresses the question she raises on page 6: why we spend so wastefully. This is despite her claim (also on page 6) that “This book is about why.”

Why do we decorate ourselves with expensive largely non-functional purchases? What interests me is not so much the conscious motivation of the consumer. Over the years, I’ve heard zillions of people give suspicious reasons for buying things they don’t need. But such conscious thoughts and articulated reasons don’t fully answer why we do the things we do. Similarly, our conscious thoughts don’t really tap into the deep reasons for pouring vast energy into other basic human activities such as eating, sleeping or having sex.

It’s important to remember that there are various kinds of “why” questions. The answers to “why” questions can include conscious motivation, as well as deeper considerations. Nobel Prize winning ethologist Niko Tinbergen has argued that each “why” question is actually four separate “why” questions. These four “why” questions concern the behavior’s:

1. Phylogeny or history (when did the behavior developed over geological time as part of the evolution of the species?).

2. Ontogeny (the behavior’s development over the life of the individual animal),

3. Function (how the behavior impacts the animal’s chances of survival and reproduction; the purpose the behavior serves in the animal’s life) and

4. Proximate cause or mechanisms (what bodily machinery, including motivational systems, produces that behavior).

Schor’s book, like most books on consumer behavior, considers only the “proximate” reasons for why humans engage in wasteful buying. What especially intrigues me is something else: a “functional” why.

Evolutionary Psychology’s Approach

There is hope for people seeking an adequate answer to the “functional-why” question. Evolutionary psychology has an interesting and somewhat satisfying story to tell: Whenever we pursue designer and luxury versions of consumer goods with gusto, we are on a quest to decorate ourselves with our purchases in an attempt to attract mates.

Amotz and Avishag Zahavi, authors of The Handicap Principle: A Missing Piece of Darwin’s Puzzle (1997) set the stage.

To understand the Zahavis, you must start with their elegant premise:

We define signals as traits whose value to the signaler is that they convey information to those who receive them . . . All signals have a cost—they impose a handicap—and . . . this is what guarantees that they are reliable.

(Page 58) Decorative markings on the bodies of animals constitute one kind of signal. We are animals too, so it shouldn’t shock us that we act like animals! We wear our fancy new car just like we wear sexy clothes. We even wear big new houses. Why do we wear such expensive clothes?

Decorative markings spread in a population when individuals who are so decorated are preferred as mates over ones who are not. This preference results when the markings in question help observers reliably identify the better individuals. It follows that those who, in fact, select the pattern, have to have some pre-existing yardstick to assess the decorated individuals. This measuring stick must enable them not only to distinguish the good from the bad, but more important, the better from the merely good. In humans, this capacity expresses itself through what is generally called sensitivity to beauty, or aesthetics.

Obviously, the markings of other species were not selected by humans; rather, females and males of the species chose as mates individuals decorated with the “right” markings, which caused the evolution of this specific decoration.

(Page 223) It bears repeating: signals must be expensive to be reliable. Our expensive (but ostentatious) consumer goods thus constitute powerful and reliable signals that we possesses the resources to provide well for a mate. It’s the apparent cost that sends the signal, not the functionality of the purchase.

Why not simply tell potential mates that we will provide well for them? It’s because there are too many people who exaggerate and lie. Nature has developed a way to weed out the cheaters, though: show, don’t tell. As documented by the Zahavis, numerous species have evolved the types of bodies and behaviors that are incredibly expensive to maintain (requiring a large diversion of the animal’s time or energy). Wasting resources wouldn’t seem to be a good way to spread one’s genes, but it is a good way to let mate know that you are resourceful enough to spend that energy and time. And the only way to spread one’s genes is to first get a mate. What might seem wasteful, then, is actually the most direct way to get the job done. It’s taking a step backwards in order to take multiple steps forward. Classic examples are the peacock’s tail and the nightingale’s complicated song.

When a trait is expensive, potential mates takes notice because the signal is reliable: The animal is showing, not just telling. Diamonds impress us more than cheap zircons, even though most people can’t tell the difference. That’s because diamonds are so expensive that people without resources can’t afford to buy (and thus display) diamonds (Hmmmm . . . .Valentine’s Day is coming up and I just found out that I can get a 1.75 carat Zircon for $43.75 . . .).

Recently, I stumbled upon a thought-provoking and entertaining article tying together these two evolutionary theory and rampant consumerism. First, a word about the author, Geoffrey Miller, an evolutionary psychologist. Miller has written of the great power of sexual selection eloquently and often.

For instance, consider Miller’s first book, The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature (2001). Here’s the basic theme of that book, according to Dylan Evans, a reviewer:

[Y]ou get a provocative thesis: the most distinctively human aspects of our minds evolved not by natural selection but by sexual selection. The things we think of as most “human”, such as our capacities for art, morality and language, Miller argues, did not evolve because they provided any survival benefit, but rather because they helped our ancestors to seduce their lovers.

In short, you might not get that woman into bed until you first prove that you “love” her. How is “love” shown? Often, it’s by convincing her (showing, not telling) that you would make a good mate, i.e., convincing her that you have the sort of biology that gives you access to the resources necessary to raise up her offspring. But we can’t see the quality of genes directly. That is why discriminating animals (including human animals) use things we can detect (e.g., the ability to purchase a huge diamond ring—one human version of the peacock’s tail) as tokens for hard-to-detect fitness. It’s an educated guess, not precise. But it’s the best we can do in this brutal daily competition of mate selection for which we are wired to engage (whether or not we consciously realize that we are competing).

Once you read Miller’s Mating Mind, you’ll never again think of art, music or the use of large vocabularies the same. If you just can’t get your hands on Miller’s book soon enough, this review by Denis Dutton might hold you over for awhile.

A caveat. Many have suggested that Miller has pushed sexual selection further than it can be legitimately be pushed and that other evolutionary pressures are necessary (At a conference I attended in Vancouver two years ago, evolutionary psychologist David Buss made this comment to me). Another caveat is the “social brain” hypothesis of human evolution, which maintains that the human brain and our language capacities both evolved in response to increasing sizes of the groups in which we lived. We needed bigger brains to keep track of friends and foes. The social brain hypothesis is thus an alternate posited source of evolutionary pressure.

I wonder, too, whether Geoffrey Miller’s approach can apply to shop-till-they-drop females. The standard story of sexual selection is about men wasting resources to display their fitness in the presence of women who choose among them. Based on my reading of The Mating Mind, I believe that Miller’s response would be that it “takes one to know one.” The female brain is made vulnerable to such extravagance as a side effect of being designed to understand extravagant male behavior sufficiently in order to take advantage of it. Perhaps he would add that the biological machinery that leans toward extravagance can’t easily be parsed out in only one sex. The outrageous consumerism of women, then, might be like the nipples found on men. It comes along for the ride in the sex it really wasn’t designed for.

“Waste: A sexual critique of consumerism.”

With all of the above as prelude, I recently learned that Miller has spun some thought-provoking and entertaining arguments that Charles Darwin’s theory of sexual selection also accounts for the consumerist madness that abounds. Miller made his arguments in a 1999 article entitled “Waste: A sexual critique of consumerism.”

[Note: Miller is currently writing a book-length version on this topic: Faking fitness: the evolutionary origins of consumer behavior.]

Miller starts his story with the same question I raised at the top of this post: Why do people spend enormous amounts of money on items that are not dramatically more functional than lower priced merchandise? In Miller’s case, he asks why someone would buy the Sennheiser top-of-the-line headphones for 9,652 British pounds when a terrific quality pair of Vivanco SR250s can be had for a mere 25 pounds. The story that makes the most sense ends up being a story about … you guessed it . . . sex.

While the Vivancos are merely good headphones, the Sennheisers are peacocks’ tails and nightingales’ songs. Buyers of top-of-the-range products understand that their prize is a benefit, not a cost. It keeps poorer buyers from owning the same product, thereby making the product a reliable indicator of their possessor’s wealth and taste. We want the Sennheisers not for the sounds they make in our heads, but for the impressions they make in the heads of others.

Consumerism is what happens when a smart ape evolved for obsessive sexual self-promotion suddenly attains the technological inventiveness and social organization to transform the raw material of nature into a network of sexual signals and status displays. It transmits a world made of quarks into a world of tiny, unconscious courtship acts. Every thing becomes a product, every product becomes a signal and every signal becomes sexual. Yet most sexual signals go unrecognized, unappreciated, and unreciprocated. The result is that fascinating phenomenon we call modern civilization, with its glory and progress, to be sure, but also with its colossal waste and incalculable alienation.

Miller argues that consumerism is “just the most recent and superficial manifestation of evolutionary pressures for sexual signaling.”

Citing the Zahavis, Miller reminds us that

many sexually selected traits, such as peacock tails, humpback whale songs, and male human aggressiveness, are so costly in time, energy and risk that they severely reduce survival chances, but evolved nonetheless for their reproductive benefits… Zahavi called these costly displays ‘handicaps’ because of their ability to indicate fitness in the reproductive domain stems directly from the way they reduce fitness in the survival domain … the handicap principle suggests that prodigious waste is a necessary feature of sexual courtships… in nature, showy waste is the only guarantee of truth in advertising.

Miller is, indeed, echoing one of the Zahavis’ most fundamental points: “Waste is the very element that makes the showing off reliable” (p. 40). Applying this principle to conspicuous consumption, Miller argues that such wasteful consumer consumption is the analogue of the peacock’s tail.

But there is no rest from the competition. The game-board is ever-dynamic. The Zahavis use the example of lace to illustrate:

When lace was made by hand by expert workers, the amount of skilled labor needed to produce it made it very expensive…. the development of machines that could cheaply manufacture lace indistinguishable from the handmade product put an end the use of lace as an indicator of wealth. Today, in fact, lace is not much used at all. By contrast, commodities like bread or iron that are used to meet direct needs rather than to send signals do not lose their usefulness if their price goes down; rather, they are used all the more. Although human cultural and economic development are different from biological evolutionary systems, the two have a very important common element: both emerge from the need to competitors have to cooperate and communicate.

Page 59. According to Miller, by intentionally advertising the high prices of luxury goods the merchants are paradoxically increasing the demand for their products and thus stoking the fires of the sexual competition:

Consumerism is a sort of virtualization of conspicuous consumption, where people display their wealth and taste by owning widely recognized products of commonly known cost… this requires demonstrating a credible three-way relationship between product, potential consumer and pool of potential mates appreciating the act of consumption… mass advertising can jumpstart this signal-evolution process by showing fake man (actors) driving not yet available Porsches, and fake women winking at them… the result can be pathological, a runaway consumerism in which an individual gets lost in a semiotic wilderness, searching for sexual signaling systems in all the wrong places.

Most of us deny that we’re out there shopping to decorate ourselves with stuff to make ourselves attractive to others. Rather, we talk about having “fun” shopping, or working hard to purchase “quality merchandise,” or we simply bask in the glow of our (mostly) non-functional purchases. That we don’t recognize our deep motivations doesn’t mean that Miller is incorrect. Powerful human motivations are usually subconscious. We usually don’t think about the biological need for nutrition when we eat. Rather, we talk about being “hungry” or “enjoying” the food. We explain our need for sex because we are “horny” rather than because of a deeply wired urge to procreate.

Miller is most clever when he points out that consumer-exploiting cartels thrive especially in the area of courtship gifts (as opposed to gifts that are simply used as courtship displays).

One risks sexual humiliation by showing an interest in good value for money when buying a romantic dinner, Valentine’s Day flowers, or an engagement ring. This fear of humiliation makes consumers reluctant to challenge exorbitant prices and exploitation of marketing, or high taxes on these luxury goods.

Speaking of holidays, you can’t consider ghastly displays of consumerism and not think of Christmas. I’ve previously written on this topic, facetiously characterizing Christmas as a “lek.”

A lek is a gathering of males, of certain animal species, for the purposes of competitive mating display . . . [T]hey spar individually with their neighbors or put on extravagant visual or aural displays (mating “dances” or gymnastics, plumage displays, vocal challenges, etc.).

Christmas would be a temporal lek, as opposed to a geographical lek. But consider that as a result of all that gift-giving (much of it jewelry and other courtship gifts), many yellow lights change to green, sexually speaking. The more I think about it, the more I like the idea of calling Christmas a “lek.”

Miller also writes about leks in The Mating Mind, page 115:

Some birds like sage grouse congregate in these leks to choose their sexual partners. The males display as vigorously as they can, dancing, strutting, and cooing. The females wander around inspecting them, remembering them, and coming back to copulate with their favorite after they had seen enough. Leks resemble music festivals, where mostly male rock bands compete to attract female groupies.

Ironies

There is an irony in the resistance that many people have to evolution. Miller argues that this resistance exacerbates conspicuous consumption. When we deny that sexual selection drives conspicuous consumption, this leaves us no systematic understanding of our own behavior. Without any comprehensive understanding of our wasteful impulses, we helplessly play right into the hands of advertisers.

Another irony Miller raises (he raises many) is that we must not moralize our hostility toward wasteful displays. He argues that this is bad for science because it shuts off analysis and “derails serious thought.” In fact, Miller suggests that the best attack is to combine the forces of two historically antagonistic approaches: evolutionary psychology and postmodernism.

Evolutionary psychology provides the sexual selection theory and the science of human nature, while cultural theory supplies the acid skepticism and semiotic insight to cut through our complacent blindness to the sex, money, power, and history behind our cultural signal systems.

Miller also argues that consumerism is soaking up our time and energy to such an extent that we are engaging in a sexual arms race instead of spending those precious resources to have the large families we used to have. Instead of spending our early adulthood “taking care of our first six toddlers” we spend our time courting each other through buying things. We don’t have enough time or money to do both. He further suggests that, were we able to immediately recognize and cease our consumerist frenzy, it might “create a population explosion.”

I think Miller’s argument could be extended much further. I think most Americans are obsessed with decorating themselves with their purchases to such an extent that they ignore the children they’ve already brought into the world, as well as ignoring their own significant others. Obsessive shopping often constitutes proto-child-neglect and proto-infidelity.

It’s war out there

Purchases are not impressive to others, unless expensive. Expensive purchases thus constitute reliable signals that the purchaser can marshal resources, thereby enhancing the purchasers’ reputation as a mate. Zahavi points out that the detriment of spending lots of money is the flip side of the benefit (the enhancement in reputation as a mate):

The reliability required in signaling militates against efficiency. Handicaps increase the reliability of signals not despite the fact that they make an animal less efficient, but because they do. Any improvement in a signal must be accompanied by a cost to the signaler—that is, it must make the signal’s bearer less well-adapted to its environment.

(p. 91) The resulting bizarre picture, then, is that of a bunch of animals (people are animals too!) competing for mates by giving themselves self-inflicted economic wounds! I am hurting myself (financially, socially or physically) to show that I’m able to do so and that, therefore, I am worthier than those other guys who have not inflicted such heavy wounds upon themselves.

The Zahavis suggest a way to really heat up this war for mates. If you REALLY want to compete, don’t just buy something expensive. Buy something expensive that is a lot like the extravagant possessions of your competitors, but make it even more expensive. For example, buy a VERY expensive suit and strut your stuff among your suit-wearing competitors. As the Zahavis write:

Why, then, do people of a given group make the effort to dress “properly.”? [W]hy do corporate executives, or members of a biker gang, dress just like other corporate executives or members of the gang? The clothing within each group is not really identical, of course. Small details-the quality of the materials or workmanship, the fit, the care taken in dressing, the way a person carries his or her clothing-vary from person to person, and the differences tell a great deal about each wearer’s means, abilities, and personality, as well as accentuating posture and behavior. It is precisely the similarity of the clothing that makes it easier for group members to assess the differences among them. If each person within the group wore wildly different clothing it would be difficult to compare them with one another in a meaningful way.

The closer the competition-the more evenly matched individuals are with regard to some desirable attribute-the more healthful uniform markings can be in exposing these fine distinctions. . . .

That’s why the battle for mates often involves similar luxury items (clothes, watches and houses). That’s why the guy with the extremely expensive stamp collection doesn’t compete well among the guys with the fancy sports cars.

Wrap-up, for now.

The evolutionary psychology of Miller is not an airtight approach to the problem of out-of-control consumerism. It raises serious questions. At this point, though, I find Miller’s approach to be one of the very few legitimate contenders on the “functional why” question. Miller certainly suggests a tantalizing logic for why humans would waste vast amounts of money for things they truly don’t need. The wine-buyer in the example at the top of this post was displaying her ability to afford wine among a winnowed field consisting of people who appreciate wine. She was trying to impress her acquaintances in a way that biologically makes sense.

Extravagant spending is certainly a problem widespread enough to suggest biological underpinnings. The energy is just too focused and too intense to be incidental or happenstance. If Miller is not exactly correct, the cause of extravagant spending must be something similar to what he suggests.

But why be concerned about people wasting their time and money? In a world where many people live desperately, there is far too much time, energy and money poured into acquiring the kinds of things that no one (absolutely no one) needed 100 years ago. The struggle for mates is incredibly serious and it will always remain so—it’s a vigorous and sometimes vicious arms race. Maybe, just maybe, there’s a better forum for staging these competitions.

Imagine if some creative-thinking running back got the bright idea that instead of running, he would grab the ball, climb into an army tank and drive down the field, mowing down hoever got in the way. A touchdown every time. If this ever really could happen, eventually, all of the other football players would start driving onto the field with their own tanks: 22 tanks lined up against each other on the field. An interesting proposition, yes, but is it still football?

It’s my conscious motivation, then, that perhaps there is a better way to compete for mates than blowing so much time and money on luxury goods. In countries where they don’t have vast amounts of consumer goods, they do compete in other ways. They find mates and life goes on.

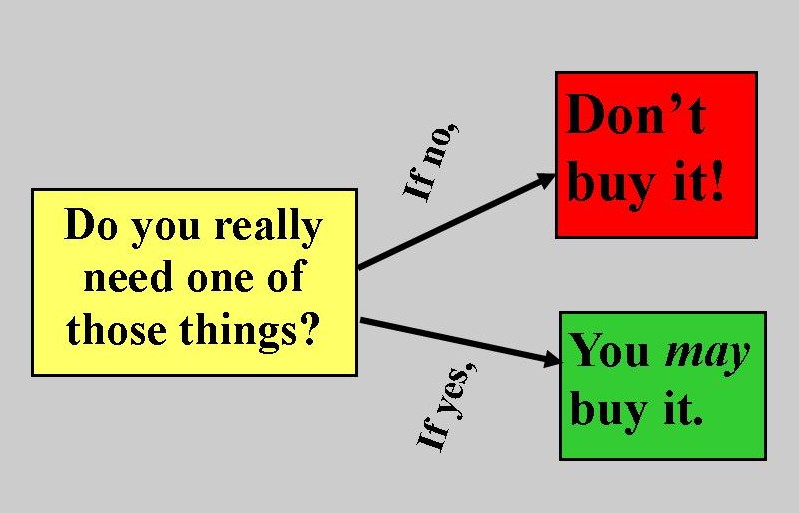

If Miller is right, it’s time to consider whether there’s a way to do the serious work of mate selection more efficiently in this vast consumer wasteland known as the U.S.A. In the meantime, if you’re fed up with rampant consumerism, here is a bit of advice I can offer (I’m especially offering it because you made it all the way down to the bottom of this especially long post:

I know that this complicated diagram lacks any connection to procreation. If you crave sex, you’re on your own. Sorry.

You probably do deserve a haircut…but I think I see your point, your kids deserve to go to college too. Who is to say that the economy/dollar will be worth anything in a decade. I agree, save your money, as much as you can, and put some of it into *Euros*. Just think about the US National Debt…with the amount we are paying on interest, inflation is going to take hold soon, and you don't want all the pennies you have been saving by using the flowbee to become worthless *US* funds.

Also, I recommend keeping an eye on your stock portfolio (401k too), or hiring somebody to do so, just in case (when) the markets start to go sour, you can jump out.

Sorry, I don't get it.

Assuming one finds pure joy in work and therefore makes more money than needed for necessities – and is charitable – what is wrong with enoying expensive cars, wine, hotel rooms, or whatever? How is that antisocial?

TMOL: My main point (in an admittedly long piece) was that competition for mates might be driving extravagant spending. I won't pretend to have perfect calculus for deciding how much it is fair for one to keep and how much to give away. In fact, I don't know that there is a meaningful answer to that question that applies to every person everywhere. My enthusiasm for writing this piece is the deep impulse to acquire such goods (something almost everyone does, to a degree).

Having said that, there is something morally suspect about the kind of people who spend profligately on luxury without attending to the despertely needy. Again, I don't pretend to have any sort of calculus worked out as to what is "fair." It's a gut feeling for me.

Here's a bit more from Geoffrey Miller, from Edge:

Click here for his entire article.

That is all a bunch of hogwash. If a person is getting all the sex they desire they still may find pleasure in driving a good car.

TMOL. I've read that there are some people who get all the sex they desire. Miller's point, however, is not about whether one is sexually satiated. It's about the deep craving to advertise for mates shared by humans and all other higher-order animals. We consciously attribute our acquisitiveness to living the "good" life. Miller is suggesting, however, that there is a powerful unconscious biologically-wired function underlying that acquisitiveness.

Even when you are absoutely in synch and physically walking with an utterly perfect significant other, does it not bring on a "glow" when another sexually attractive person responds to your accomplishments, intellect, creative skills or (as Miller suggests) high-quality possessions?

Your ask: "Even when you are absoutely in synch and physically walking with an utterly perfect significant other, does it not bring on a “glow” when another sexually attractive person responds to your accomplishments, intellect, creative skills or (as Miller suggests) high-quality possessions?"

don't know.

never happened.

yet.

but i do like driving a fast car.

I LOVE the flowbee! I cut my own hair too. Last time I did, it looked so much better than most hair parlor cuts. I've been cutting my own for about 3 years now, the first couple times were pretty choppy but perseverance and practice!

I have a question about this:

"Miller argues that this resistance exacerbates conspicuous consumption. When we deny that sexual selection drives conspicuous consumption, this leaves us no systematic understanding of our own behavior. Without any comprehensive understanding of our wasteful impulses, we helplessly play right into the hands of advertisers."

…How? How would you play into the hands of advertisers by turning your back on needless consumerism? Wouldn't the purchase decision be one based on utility and personal satisfaction, rather than an advertised 'suggested' value of enhanced sexual fitness?

To David Koerner: I think that Miller is suggestion that in this realm of runaway consumer spending (and in most other fields of human behavior), the first best step for making changes is to understand why we behave in this way in the first place.

Knowing that we are prone to displaying for reasons rooted in ancient desires related to access to partners for procreation just might make us think twice about whether we really "need" that expensive new sports car. That same underlying explanation might also suggest to us alternative ways of displaying that serve that same deep need (e.g., volunteering for a worthy cause can also a powerful display of fitness).

I look forward to reading Miller's new book on consumerism. He is a terrific writer and thinker.

Erich,

I've attempted laying out the foundations for why we consume in this piece:

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/3386

I will attempt to turn it into an academic paper, which is how I found your interesting post – by googling.. Nice work

Nate: Thanks for checking in with us. I read your Oil Drum post. Lots of good information there. I'm especially intrigued by this:

I do like your coupling with the limitless need to seek status through squandoring resources with the fact that information is limitless. That would seem to be a much safer battleground (at least for those who are proficient absorbers and processors of information!). Good luck with your project. When you are finished, let us know the link.

Thank you.

The problem with competing for information, as I mentioned, is what do we DO with the information once it's acquired. To date, information leads to power leads to money leads to resource consumption, etc. To compete just for the information we would all have to take a step towards zen-buddhist land, which wouldn't be a bad thing – just seemingly implausible as I look out my window….;-)

Interesting Article – keep up the good work 🙂

Also, what is the theme have you installed at the moment? I want to know if it's a free one.

Eve: The theme I'm switching to is Solostream's WP-Vybe, an outrageously reasonably priced WordPress template ($99). I am compelled to add (because it is utterly true–I'm saying this merely as a satisfied customer), the WP-Vybe support is extraordinary. I'll post more on this theme in a separate post, once I finish installing all the bells and whistles (i.e., plugins). http://www.solostream.com/2008/08/01/wordpress-th…

Appreciate your quality work.. thanks for sharing…

This a great great piece. Well done really enjoyed it.

It's also very long and very clever – I hope your peers and your wife read it – otherwise your flower has wasted it' sweetness on the desert air …

I personally found myself overwhelmed by your physical attractiveness (courtesy of flowbee), your fine fettled mental health, intelligence and personality (high conscientousness) – a fine display indeed and no doubt costly.

Keep it up 🙂

The common man: I really do use the Flowbie. It is a wonderful way to protest. I have no connection to the company, but I tout it. After I use it, I walk up to an unsuspecting victim, usually a prim and proper woman at work. I say, "I just went to a new hair stylist today. How did she do on my haircut?"

The response is invariably, "Oh, don't worry. It looks great. Really well done."

Me: "Are you sure? Because I'm really particular about my hair."

[Victim]: "No, really. It looks great. No problem at all."

Me: "Now the truth. I really cut my own hair with a device called the Flowbee. I is a clipper gadget that I attach to a vacuum cleaner."

Then I look at the horrified look. I usually need to explain several times that I REALLY use Flowbee, and that I was setting them up with the initial story about the new salon stylist.

For me, this is a powerful illustration that it's mostly not about the haircut. It's about the fact that you are displaying by telling people that you pay $35 for a haircut. Otherwise, why wouldn't people say (when the ruse is revealed): "Gad, that must really be one amazing gadget. I'm impressed." No on has ever followed up like that. It's always a horrified look.

Erich: This is a highly thought-provoking piece. But I see some major flaws with a few of Miller's theses based on my own experience.

Recently my wife and I bought a 2011 mini-van, the first new car we've bought in 16 years. It's very hi-tech, shiny and beautiful. And expensive (at least as measured my meager bank account). But, according to Miller, the real reason I decided to spend so much money on such a piece of conspicuous consumption is as a way to flaunt my sexual attractiveness and fitness, and to seduce females who will bear my offspring. Trust me, those were not the reasons.

I can state unambiguously that the only reason we bought this expensive van is because our 12-year-old minivan had just died. I spent weeks looking for a used minivan so I could save a few bucks. If I was looking for sex, I would have poured that money into a new sports car according to Miller's theory.

Indeed, using my new, shiny minivan as a way to find new sexual partners, or even obtaining more sex from my wife —- sorry, folks, it's just not going to happen. Not after nearly 20 years of marriage and three sons. Buying that van was for purely pragmatic reasons, i.e., the need for safe and reliable family transportation for the next decade or so.

Same goes for the used Specialized mountain bike I bought from Recycled Cycles in University City, Mo. nearly 10 years ago. It's a great bike, but it's banged up with a nicked paint job (kind of like its owner). I spent extra bucks on the bike not because it will draw hot babes my way (as if!), but because it won't crap out on a steep mountain trail and spill my sorry ass. Once again, pure pragmatism trumped any other factor.

I do agree that consumerism in America is rampant and that it does comprise a secular religion for many Americans. I also agree that sex and the marketplace walk hand-in-hand, a fact codified by the Madison Avenue mantra of "Sex sells."

But many other factors, I submit, guide our purchasing decisions. And for me it's more often than not the desire save a few bucks. But, hey, maybe I'm just weird that way.