All my life I’ve been suspicious of the alleged power of syllogisms. Here is an often-cited syllogism:

• All men are mortal

• Socrates is a man

• Therefore Socrates is mortal

Syllogisms can be expressed in this logical form:

• All B’s are C

• A is a B

• Therefore, A is C

The above example is a perfect syllogism: the conclusion naturally follows from the premises. Syllogisms constitute deductive reasoning (from a given set of premises the conclusion must follow).

Many excellent thinkers and writers have stressed the need to present one’s arguments in terms of syllogisms. For example, in his excellent book on legal writing, The Winning Brief, Bryan Garner advises lawyers to frame every legal issue as a syllogism (see p. 88).

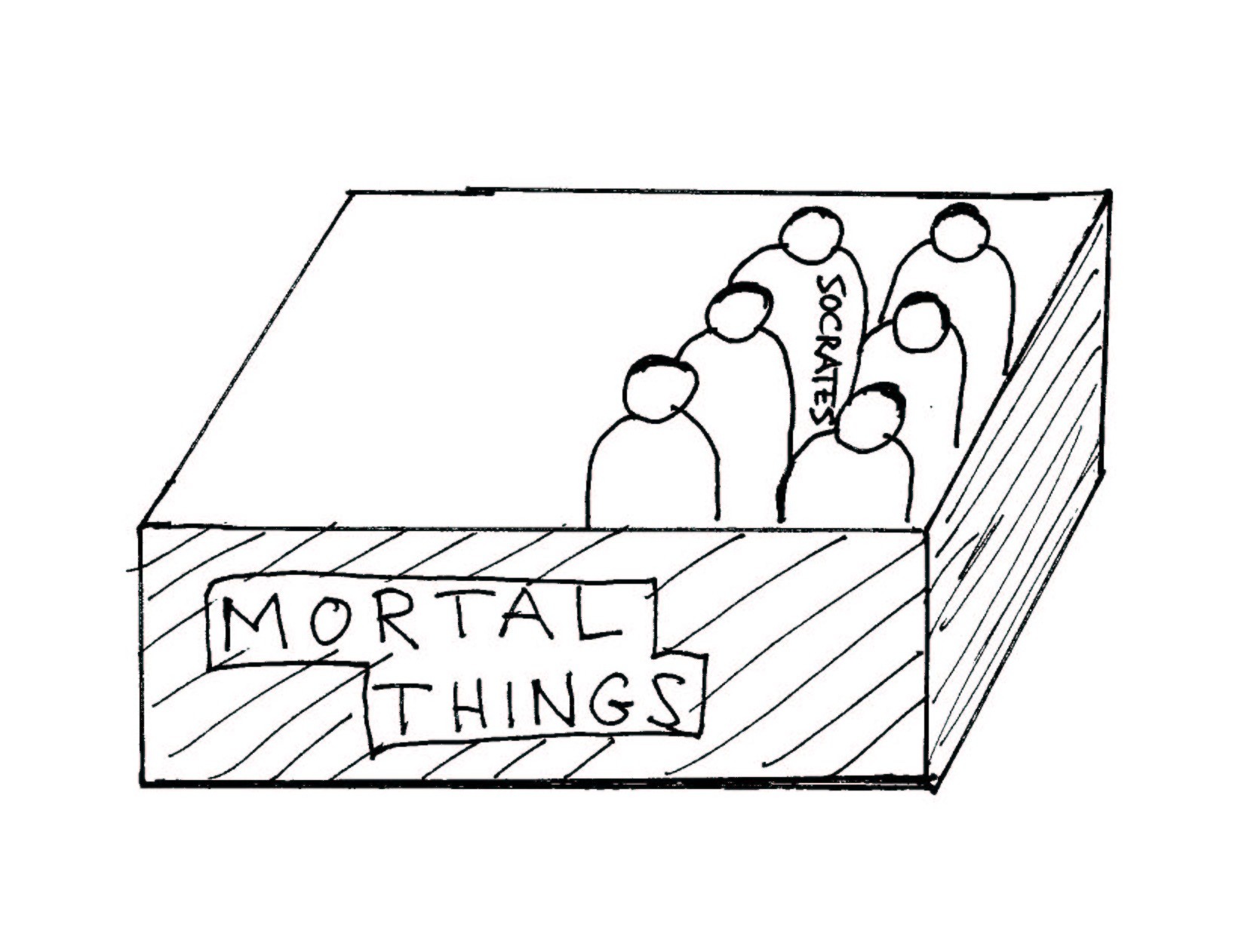

But what is really behind the power of syllogisms? It turns out that they are actually based on a metaphor—the metaphor of objects in a box. Consider this diagram in tandem with the classic syllogism (“All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal”)

As Judge Posner points out (in “The Jurisprudence of Skepticism,” 86 Mich L. Rev 827, 830 (1988)), the first premise presents a box labeled “all men,” in which each of the contents are each labeled “mortal” and one of those objects is labeled “Socrates.” Posner notes,

“The second premise tells us that everything in the box is tagged with a name and that one of the tags says “Socrates.” When we pluck Socrates out of the

…