“Racist” Princeton’s Serious Legal Dilemma

[Princeton] President Christopher Eisgruber published an open letter earlier this month claiming that "racism and the damage it does to people of color persist at Princeton" and that "racist assumptions" are "embedded in structures of the University itself."

According to a letter the Department of Education sent to Princeton that was obtained by the Washington Examiner, such an admission from Eisgruber raises concerns that Princeton has been receiving tens of millions of dollars of federal funds in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which declares that "no person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

Fascinating. Princeton has made a unambiguous statement that it has been thoroughly "racist" and that it continues to be "racist." The Department of Education responded by opening an investigation because this statement conflicts with many other claims Princeton made, in order to qualify for federal funding, that it was not racist. Now we'll see whether Princeton really meant what it said. The Department of Education will demand evidence from Princeton in support of Princeton's admission. The National Examiner explains:

What the department seeks to obtain from its investigation is what evidence Princeton used in its determination that the university is racist, including all records regarding Eisgruber's letter and a "spreadsheet identifying each person who has, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, been excluded from participation in, been denied the benefits of, or been subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance as a result of the Princeton racism or 'damage' referenced in the President’s Letter." Eisgruber and a "designated corporate representative" must sit for interviews under oath, and Princeton must also respond to written questions regarding the matter.

What did Princeton mean when it admitted that the University was permeated with "racism." For reference, Merriam-Webster’s current entry on “racism” (as of August 7, 2020) gives three, related definitions:

D1. a belief that race is the primary determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences produce an inherent superiority of a particular race

D2. (a) a doctrine or political program based on the assumption of racism and designed to execute its principles, (b) a political or social system founded on racism

D3. racial prejudice or discrimination

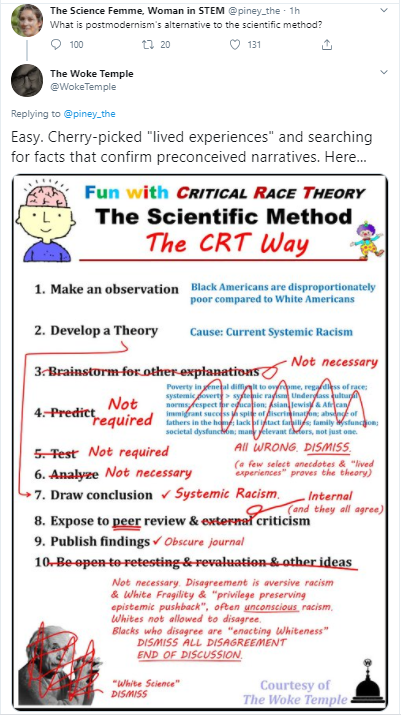

Perhaps Princeton was using the new Woke definition of "racism," but it might have put itself at serious financial and legal risk to use "racism" in this new highly-disputed sense. Perhaps this is a good time to come to a careful consensus about what the vast majority of people mean when they use the term "racist." It's time to stop being 1) sloppy or 2) engaging in blithe virtue signalling when using such an important word. New Discourses discusses a controversy regarding the definition of "racism." Here is an excerpt from that article at New Discourses:

When critical social justice theorists talk about “racism,” they describe it as a matter of a social system’s being organized in such a way that it creates and perpetuates racial inequalities regardless of the conscious beliefs, attitudes, or intentions of those who inhabit the system. Although they also make much of purported unconscious biases in the propagation of racism, even in systems, their criterion for diagnosing systemic racism is entirely consequentialist: “disparate impact” along racial lines is its sole necessary and sufficient condition. For example, in White Fragility, Robin DiAngelo asserts that “[b]y definition, racism is a deeply embedded historical system of institutional power (24), “a system of unequal institutional power,” (125) “a network of norms and actions that consistently create advantage for whites and disadvantage for people of color,” (27–28), “a far-reaching system that no longer depends [as per D2] on the good [or bad] intentions of individual actors; it becomes the default of the society and is reproduced automatically,” (21) i.e., without conscious intent. Journalist Radley Balko’s gloss on “systemic racism” captures the idea perfectly:To be continued . . .Of particular concern to some on the right is the term “systemic racism,” often wrongly interpreted as an accusation that everyone in the system is racist. In fact, systemic racism means almost the opposite. It means that we have systems and institutions that produce racially disparate outcomes, regardless of the intentions of the people who work within them.

In light of such statements, D2 would seem to fall short by failing to make a clean separation between human psychology (beliefs, intentions, etc.) and the quasi-mechanistic, or “automatic,” operations of social systems.