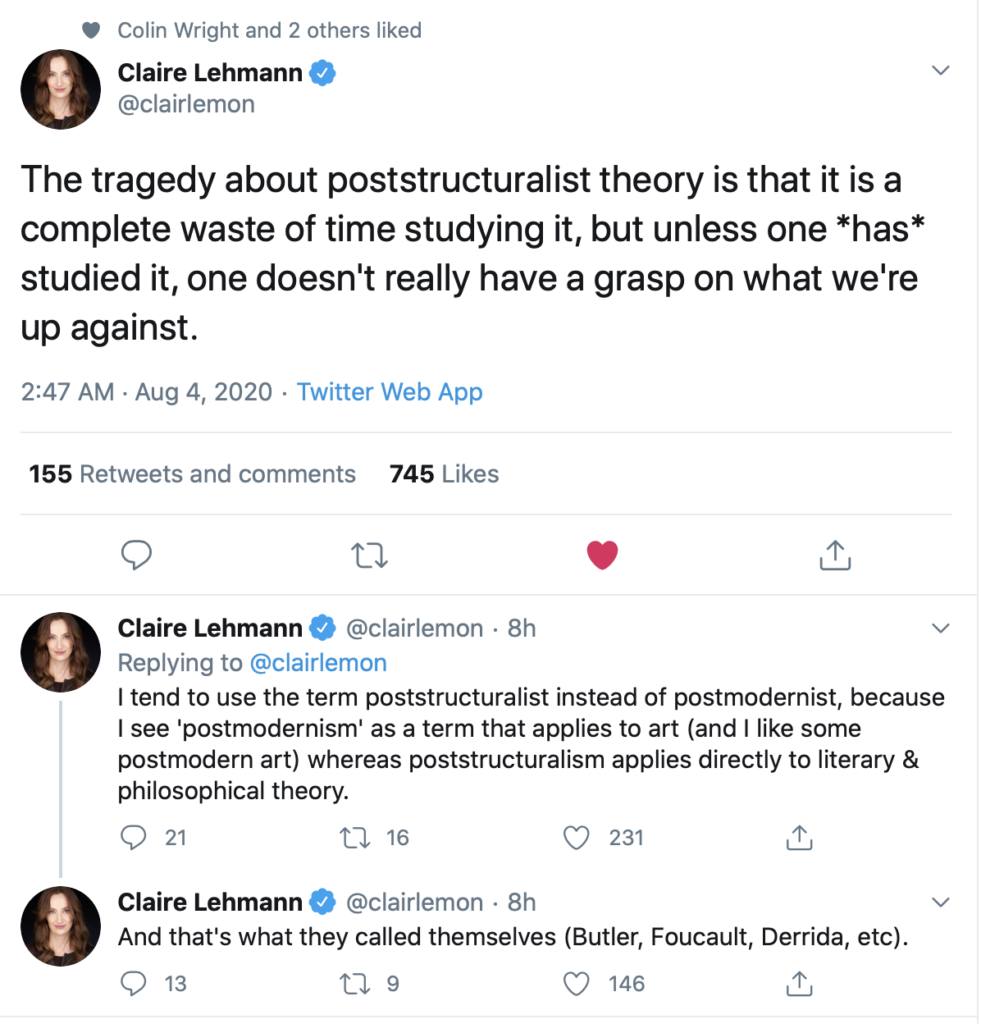

Claire Lehmann is Editor of Quillette. She nailed it in the Tweet below.

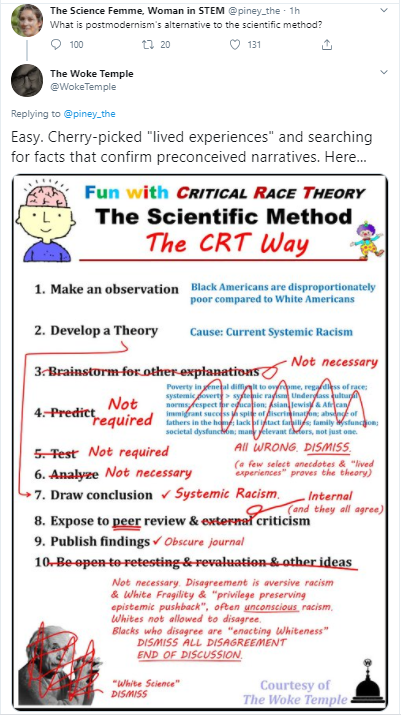

The Woke movement (she terms it "post-structuralist" thought) is a fermenting vat of vague, self-contradictory claims, much of them unhinged from the analytical evidence-based Enlightenment tradition that has proven itself by sending people to the moon. Wokeness functions as a Trojan horse; it looks like something good, but functions to disarm skeptical analytical thought. It functions much like fundamentalist religion, elevating raw feeling above analytical thought.

We need to meet Wokeness on its own terms if we are to show where it has gone astray. The challenge is that it requires a substantial investment to become fluent in Woke. Further, fully engaging seems like a non-ending exercise, given the continuous propagation of new ad hoc Woke concepts. Is it even possible to have a conversation where one side disparages analytical thinking, self-critical thought and even mathematics? It's the equivalent of sending a time-traveling Enlightenment thinker back to the Dark Ages to discuss the scientific method with Middle Age Church leaders.

I'm looking for the sweet spot--enough familiarity that I can demonstrate to timid outsiders that the Wokeness is drenched in destructive anti-intellectualism. Woke thought is also sprinkled with some salient legitimate concerns and emotionally-charged factual accuracies, however, so one needs to read and listen carefully.

Much of the danger can be nullified by putting the definitions of key Woke terms under the spotlight, terms such as "anti-racism, "critical," "systemic racism" and "gender." Modern Discourses has compiled an excellent encyclopedia for understanding the origin and meaning of these terms by the Woke, as well as additional commentary.

In the meantime, how does one most efficiently convey this danger of Woke thought to the great majority of Americans, who are quietly hunkering down, waiting for this wave of socially-reverse-engineered thought to pass over? How does one best warn that this wave of anti-intellectualism and stifled inquiry will be around for a long time, given that a loud (but relatively small) mob of Woke activists has cowed the two key institutions that should be fighting the hardest against it (media and universities)?

That is our plight.