Ubiquitous conspicuousity

At a park to weeks ago, a musician started singing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” I was talking with an acquaintance, who immediately pulled out his smart phone, clicked on a few buttons and brought up the movie “The Wizard of Oz” to play on his 1 ½” screen. He explained that he loved the movie and that he could watch it wherever he wanted. Impressive technology? Of course, but watching “The Wizard of Oz” (or any movie) is never such an important thing that I'd need to carry it in my pocket. Was my acquaintance really trying to tell me about his love of "The Wizard of Oz," or was he subconsciously trying to communicate something else to me? For many years we’ve been trying to convince ourselves that electronics manufacturers were right that we HAD to have their gadgets, including 50" screen HD TVs. For decades, we’ve been convincing ourselves that electronic audio manufacturers were correct that we “needed” to plunk down $2,000 for high-end audio components with thick copper cables lest the sound degradation would piss us off too much to enjoy our music.

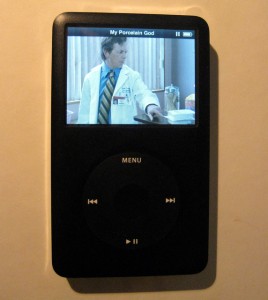

But here we are in an age where small is cool, and we’re somehow able to enjoy full length movies on tiny lo-res phone and iPod screens. And people are somehow surviving with small low-res youtube videos. And consider that the music almost everyone is enjoying on their mp3 players is sampled at a noticeably lower rate than CD-quality. And consider that CD quality sample rates are severely degraded compared to live music. But somehow we’re now OK with far less than perfect because small and convenient and high tech are cool.

I’m in the process of reading Geoffrey Miller’s riveting new book, Spent: Sex, Evolution and Consumer Behavior. We’ve all heard of conspicuous consumption (originally coined by Veblen). Miller refines and extends Veblen's concept, setting out the differences between conspicuous waste, conspicuous precision and conspicuous reputation as signaling principles. Cars exemplifying these three principles would be the Hummer (waste), Lexus (precision) and BMW (reputation). Conspicuous precision “can be achieved only through time, attention, and diligence, while conspicuous reputation (brand names) reflects a “vulnerability to social sanctions.” Most products exhibit each of these three forms of “signal reliability.” Other signaling principles including conspicuous rarity (exotic pets or pink diamonds) and conspicuous antiquity (ancient coins).

I find it interesting how much we fool ourselves about how much we “need” products based on these qualities. We “needed” large high-quality electronic audio and visual players until it became a much more impressive display to have extremely small portable electronics. It turns out that our “need” for things isn’t ultimately about need for the product’s qualities. It’s about trying to impress others with our ability to differentiate and afford various types of products.

A few years ago, I was looking at stunning images of a coral reef on the big new HD TV sets at Costco. I asked my wife whether we should think about “moving up” to a HD TV set. She asked me: “How often have you been watching a movie on our 25-year old TV set when it occurred to you that you weren’t enjoying the show because the screen was not huge or high definition? I answered truthfully: never. We still have our quarter-century old TV set and I’ve never again been tempted to “move up.” But I also admit that if I were trying to impress people today, I wouldn't be able to do it by showing off my TV. I wouldn’t be signaling that I can notice and afford fine engineering tolerances. I might show off my TV nonetheless, to signal my frugality, but my old TV wouldn’t be impressive to modern-day Americans, given that it is not (today) an expensive signal in any sense—I could buy a TV like mine very cheaply indeed at a garage sale.

Miller's book is a powerful reminder that our "need" to buy SO many things is often not about the things themselves, but about the need to tell the world something about ourselves in order to increase our social status or to attract mates.

Miller has a lot to say about the differences among the types of conspicuosity. For instance, Aristocrats eschew conspicuous waste. They tend to hone in on conspicuous precision and reputation.

For more on Miller’s theory, see this book review at the NYT.

For many years we’ve been trying to convince ourselves that electronics manufacturers were right that we HAD to have their gadgets, including 50" screen HD TVs. For decades, we’ve been convincing ourselves that electronic audio manufacturers were correct that we “needed” to plunk down $2,000 for high-end audio components with thick copper cables lest the sound degradation would piss us off too much to enjoy our music.

But here we are in an age where small is cool, and we’re somehow able to enjoy full length movies on tiny lo-res phone and iPod screens. And people are somehow surviving with small low-res youtube videos. And consider that the music almost everyone is enjoying on their mp3 players is sampled at a noticeably lower rate than CD-quality. And consider that CD quality sample rates are severely degraded compared to live music. But somehow we’re now OK with far less than perfect because small and convenient and high tech are cool.

I’m in the process of reading Geoffrey Miller’s riveting new book, Spent: Sex, Evolution and Consumer Behavior. We’ve all heard of conspicuous consumption (originally coined by Veblen). Miller refines and extends Veblen's concept, setting out the differences between conspicuous waste, conspicuous precision and conspicuous reputation as signaling principles. Cars exemplifying these three principles would be the Hummer (waste), Lexus (precision) and BMW (reputation). Conspicuous precision “can be achieved only through time, attention, and diligence, while conspicuous reputation (brand names) reflects a “vulnerability to social sanctions.” Most products exhibit each of these three forms of “signal reliability.” Other signaling principles including conspicuous rarity (exotic pets or pink diamonds) and conspicuous antiquity (ancient coins).

I find it interesting how much we fool ourselves about how much we “need” products based on these qualities. We “needed” large high-quality electronic audio and visual players until it became a much more impressive display to have extremely small portable electronics. It turns out that our “need” for things isn’t ultimately about need for the product’s qualities. It’s about trying to impress others with our ability to differentiate and afford various types of products.

A few years ago, I was looking at stunning images of a coral reef on the big new HD TV sets at Costco. I asked my wife whether we should think about “moving up” to a HD TV set. She asked me: “How often have you been watching a movie on our 25-year old TV set when it occurred to you that you weren’t enjoying the show because the screen was not huge or high definition? I answered truthfully: never. We still have our quarter-century old TV set and I’ve never again been tempted to “move up.” But I also admit that if I were trying to impress people today, I wouldn't be able to do it by showing off my TV. I wouldn’t be signaling that I can notice and afford fine engineering tolerances. I might show off my TV nonetheless, to signal my frugality, but my old TV wouldn’t be impressive to modern-day Americans, given that it is not (today) an expensive signal in any sense—I could buy a TV like mine very cheaply indeed at a garage sale.

Miller's book is a powerful reminder that our "need" to buy SO many things is often not about the things themselves, but about the need to tell the world something about ourselves in order to increase our social status or to attract mates.

Miller has a lot to say about the differences among the types of conspicuosity. For instance, Aristocrats eschew conspicuous waste. They tend to hone in on conspicuous precision and reputation.

For more on Miller’s theory, see this book review at the NYT.