Today on FB, I displayed this photo of Joe Biden and made this comment:

I'm all for wearing a mask when you need to be near other people, but really? A Twitter comment (see the comments here): "Virtue Signalling knows no distance."

The post drew considerable criticism that caused me to better explain my concern. I did that as an addendum to the original post, as follows:

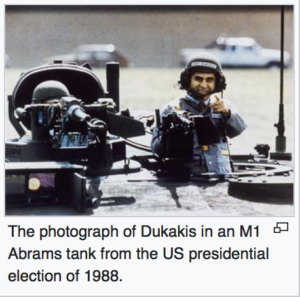

Biden's job is to either have Trump voters switch over to him or to convince them that they don't care enough that they simply won't vote for Trump (I know  several Republicans of this latter type). I don't want this election to be a repeat of Michael Dukakis riding in the tank. I fear that this type of image is going to be repeatedly and effectively exploited by Republicans to make the argument that Biden is not a strong and courageous leader.

several Republicans of this latter type). I don't want this election to be a repeat of Michael Dukakis riding in the tank. I fear that this type of image is going to be repeatedly and effectively exploited by Republicans to make the argument that Biden is not a strong and courageous leader.

The CDC has repeated and strongly warned that we maintain a distance of six feet from other people. CDC further "advises" that people wear homemade masks. I fear that this type of image of Biden sitting 15 feet apart AND wearing a mask is going to be repeatedly and effectively exploited by Republicans to make the argument that Biden is not a strong and courageous leader. There are many other images that will be used by Trump, including images where Biden and his wife are wearing masks where no other people are nearby.

Those of us who have the strength and courage to unplug from the political matrix instantly realize that this exploit that will certainly be used by Trump will be effective when compared to "fearless" images of Trump NOT wearing a mask. Who do you want as the leader of the United States? The man who worries about invisible germs that kill only 1% of people? Or a courageous man like Trump? That will be the argument and (based on the rhetoric of the clamor-to-reopen-crowd) this argument will siphon votes away from Biden.

Biden will get the votes from his base, more or less, no matter what he does between now and November, despite his many flaws. Further, his base will forgive him the "sin" of not wearing a mask while sitting 15 feet from one other person outdoors. And, as one of the commenters on my FB page indicated, Biden took off his mask for the actual interview. Good. But this image will live on in isolation from the fact that he took off the mask to conduct the interview, as will thousands of similar images of Biden.

Unfortunately, there are real consequences in the balance. Should Biden be 99% safe or 99.99999% safe? It's not a decision for me to make, but while prudent mask-wearing is absolutely a good thing, mask-wearing that looks weak and paranoid will hurt Biden's chances in November. It is my concern that the cheap version of virtue signaling suggested by this image will be quickly sniffed and identified as such by all voters who aren't already for Biden. Many of the people who are already strongly for Biden might will be oblivious to this serious problem.

I'll add one more thing. We need to be sensitive to the difference between cheap virtue signaling and expensive virtue signaling. What looks impressive when done by people we believe to be on our team can look terrible when done by members of the other team. There a lot going on under the hood and it includes confirmation bias and displaying of "badges" of in-group membership. This difference is explained by Geoffrey Miller in this definitional section from his new book, Virtue Signaling: Essays on Darwinian Politics and Free Speech (2020):

We all virtue signal. I virtue signal; you virtue signal; we virtue signal. And those guys over there, in that political tribe we don’t like – they especially virtue signal. (Just as they believe that we do.) Let’s not pretend otherwise. We are humans, and humans love to show off our moral virtues, ethical principles, religious convictions, political attitudes, and lifestyle choices to other humans. We have virtue signaled ever since prehistoric big-game hunters shared meat with the hungry folks in their clan, or cared for kids who weren’t their own.

There’s virtue signaling, and then there’s virtue signaling. This book is about both kinds. On the one hand, there’s what economists call ‘cheap talk:’ signals that are cheap, quick, and easy to fake, and that aren’t accurate cues of underlying traits or values. When partisans on social media talk about political virtue signaling by the other side, they’re usually referring to this sort of cheap talk. Virtue signaling as cheap talk includes bumper stickers, yard signs, social media posts, and dating app profiles. The main pressure that keeps cheap talk honest is social: the costs of stigma and ostracism by people who don’t agree with your signal. Wearing a ‘Make America Great Again’ hat doesn’t cost much money, but it can cost you friendships. On the other hand, there’s virtue signaling that’s costly, long-term, and hard to fake, and that can serve as a very reliable indicator of underlying traits and values. This can include volunteering for months on political campaigns, making large, verifiable donations to causes, or giving up a lucrative medical practice to work for Doctors Without Borders in Haiti or New Guinea. The key to reliable virtue signals is that you simply couldn’t stand to produce them, over the long term, if you didn’t genuinely care about the cause.

[V]irtue signaling can … be the worst of human instincts. It drives most of partisan politics, especially on social media. It drives the demands to censor, fire, cancel, and ostracize people who express the wrong opinions. It drives moral panics about satanic ritual abuse, ‘rape culture,’ and ‘porn addiction.’ It drives white nationalists to run over protesters. It drives antifa to beat up journalists. … Some of this is cheap talk, but some of it is reliable signaling. What distinguishes good virtue signaling from bad virtue signaling isn’t just the reliability of the signal. It’s the actual real-world effects on sentient beings, societies, and civilizations.

[I attempted to find the source of the photo, which I spotted on Twitter, but was unsuccessful]