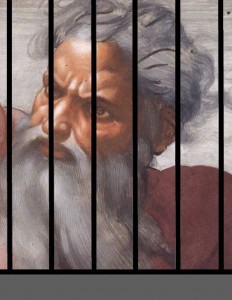

God is good

Prologue: This post does not apply to Christians who conclude that "God" was evil to the extent that "He" killed babies. Nor does it apply to Christians who don't believe that the Old Testament is literally true, and further conclude that "God" never actually killed babies as described in the Old Testament. In short, this post applies only to those who believe that A) God really killed numerous little babies, and B) that God is nonetheless "good." Whenever I hear believers proclaim that “God” is “good” I am puzzled. How could it possibly be that an all-knowing and omnipotent being could engage in the many atrocities attributed to “God” in the bible? For example, how can killing little babies ever be considered to be good? Here are 1,199 more examples of cruelty from the Bible. Anyone but “God” who engaged in such behavior would be universally proclaimed to be evil, not good. There’s no way to avoid this conundrum for believers, especially for Bible literalists. The God they repeatedly praise purportedly killed many thousands of innocent people, including countless numbers of babies. Consider also, that other Bible passages show little regard for the lives of infants and fetuses. The above passages cause me to consider this question: Do believers sincerely believe their claims that “God” is “good,” or are they merely being practical in the face of the threat of hell? To what extent is it that it is the perceived threat of hell causes it to seem “true” that a baby-killing God is “good”? Sam Harris raises a similar issue at page 33 of his new book, The Moral Landscape (2010):

What if a more powerful God would punish us for eternity for following Yahweh’s law? Would it then make sense to follow Yahweh’s law “for its  own sake”? The inescapable fact is that religious people are as eager to find happiness and to avoid misery as anyone else: many of them just happen to believe that the most important changes in conscious experience occur after death (i.e., in heaven or in hell).

own sake”? The inescapable fact is that religious people are as eager to find happiness and to avoid misery as anyone else: many of them just happen to believe that the most important changes in conscious experience occur after death (i.e., in heaven or in hell).