Dr. Peter Hotez, Vaccination Expert – Featured by Matt Orfalea

Dr. Peter Hotez guides us through the pandemic, this way and then that way. But he is an Expert all the way, as Matt Orfalea shows us:

FIRE’s Model Legislation Prohibiting Universities from Requiring Faculty Member to Make Loyalty Pledges or Ideological Commitments

In February, FIRE announced its model legislation that would prohibit all political litmus tests by universities, including DEI statements. I am fully in support. Here is a link to the Model Legislation. What follows is an excerpt from FIRE's announcement:

FIRE warned in a statement last year that the First Amendment “prohibits public universities from compelling faculty to assent to specific ideological views or to embed those views in academic activities.” But colleges have not stopped imposing political litmus tests on students and faculty in the guise of furthering DEI efforts.

Vague or ideologically motivated DEI statement policies can too easily function as litmus tests for adherence to prevailing ideological views on DEI.

[In February, 2023 FIRE introduced model legislation that] prohibits the use of political litmus tests in college admissions, hiring, and promotion decisions. Legislation is strong medicine, but our work demonstrates the seriousness of the threat. While the current threat involves coercion to support DEI ideology, efforts to coerce opposition to DEI ideology would be just as objectionable. Attempts to require fealty to any given ideology or political commitment — whether “patriotism” or “social justice” — must be likewise rejected.

To that end, because we are cognizant of the endless swing of the partisan pendulum, FIRE’s legislative approach bans all loyalty oaths and litmus tests, without regard to viewpoint or ideology. In an effort to avoid exchanging one set of constitutional problems for another, our model legislation prohibits demanding support for or opposition to a particular political or ideological view. We believe this approach is constitutionally sound and most broadly protective of student and faculty rights, both now and in the future.

FIRE strongly believes that loyalty oaths and political litmus tests have no place in our nation’s public universities. Given the pernicious threat to freedom of conscience and academic freedom we have seen on campus after campus over the past several years, legislative remedies are worthy of thoughtful consideration. We look forward to further discussion with both supporters and critics about how best to ensure that our nation’s public colleges and universities remain the havens for intellectual freedom they must be.

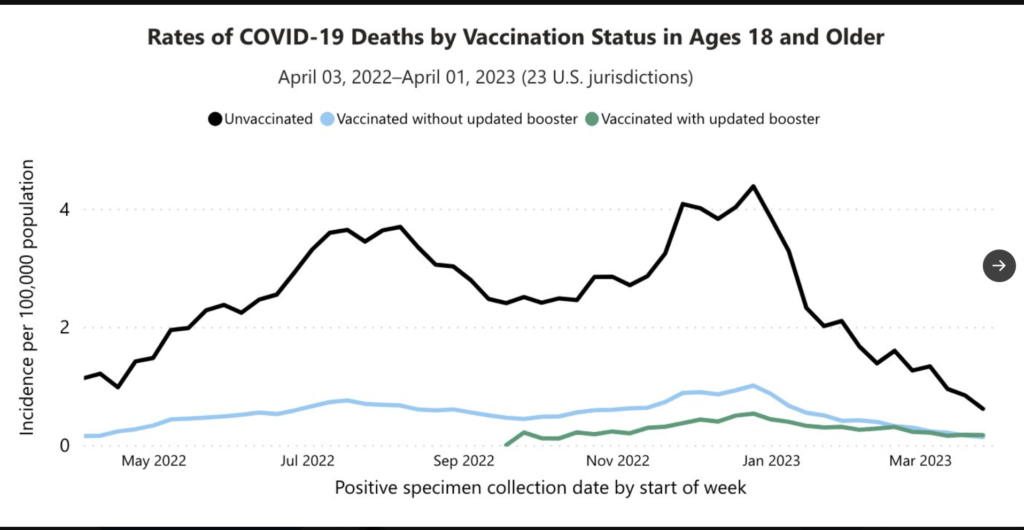

CDC’s Easy Solution to Inconvenient COVID Data

Matt Orfalea points out the problem and the CDC "solution."

---

I will now summarize the CDC position: We are so absolutely certain that unvaccinated deaths will ALWAYS be higher than unvaccinated deaths, that we are going to stop collecting this data.

San Francisco Crumbles

You can probably find a cheap hotel room in downtown San Francisco now. Social Justice ideology is destroying the city. Shellenberger has written an entire book on this decay. Read his Tweet thread and weep for a once great city.

- Go to the previous page

- 1

- …

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- …

- 452

- Go to the next page