I'm reading a 900-page compendium of George Carlin's written works: 3 x Carlin. It includes a full copy of Napalm and Silly Putty, a book Carlin published in April, 2001. Take a look at this excerpt from the chapter Carlin titled "Airport Security" (p. 325):

I'm getting tired of all the security at the airport. There's too much of it. I'm tired of some fat chick with a double digit IQ and a triple digit income rootin' around inside my bag for no reason and never finding anything. Haven't found anything yet. Haven't found one bomb in one bag. And don't tell me, "Well the terrorists know their bags are going to be searched, so now they're leaving their bombs at home." There are no bombs! The whole thing is fuckin' pointless.

And it's completely without logic. There's no logic at all. They'll take away a gun, but let you keep a knife! Well, what the fuck is that? In fact, there's a whole list of lethal objects they will allow you to take on board. Theoretically, you could take a knife, an ice pick, a hatchet, a straight razor, a pair of scissors, a chainsaw, six knitting needles, and a broken whiskey bottle, and the only thing they say to you is, "That bag has to fit all the way under the seat in front of you."

And if you didn't take a weapon on board, relax. After you've been flying for about an hour, they're gonna bring you a knife and fork! They actually give you a fucking knife! It's only a table knife--but you could kill a pilot with a table knife. It might take you a couple of minutes. Especially if he's hefty. But you could get the job done. If you really wanted to kill the prick . . .Or suppose you just had really big hands, couldn't you strangle a flight attendant? . . .

. . .

Airport security is a stupid idea, it's a waste of money, and it's there for only one reason: to make white people feel safe!. That's all it's for. To provide a feeling, an illusion of safety in order to placate the middle class. Because the authorities know they can't make airplanes safe; too many people have access.

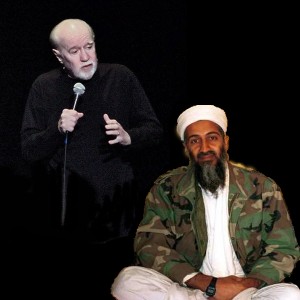

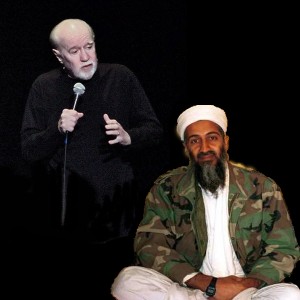

Indeed, George Carlin pretty much summed up American airline security back in April 2001. Consider what happened only five months after he wrote these words, a dramatic series of attacks that depended on the lax American security described by Carlin, as well as

the less-than-brilliantly-conceived strategy of allowing flimsy doors to the cockpit.

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, American political and military leaders elevated Osama Bin Laden to the status of alleged evil genius, essentially to give themselves cover for the pathetic

American security protocol described by Carlin. The American establishment embraced bin Laden as an evil genius because it served

two purposes. A) It was an attempt to deflect criticism from the abject stupidity of the American approach to airline security; recognizing the "genius" of bin Laden allowed hawks to continue with their mantra that Americans can do no wrong, and it was an exceptional and evil man that spilled American blood; B) Calling bin Laden a genius and broadcasting his brown-skinned non-English speaking image all over Televisiondom justified pouring

trillions of dollars into America's warmongering-torturing-spying machine; it "justified" an immense job-security program for those who wanted to use those many of those exciting Yankee weapons of war to pretend to solve complex international social and economic problems. And lots of bombs have been dropped ever since.

Here we are, a decade later, with our economy and our infrastructure on the verge of a second collapse, with almost nothing good to show for all of that money we've poured into our wars of discretion. We Americans continue to demonstrate that we are absolutely incapable of self-critical self-examination, in that we

continue to pour

two billion dollars per week into our Afghanistan adventure despite the lack of any meaningful military objective. It's merely

an adventure in sunk costs (and

see here). And the American corporate media cozily continues to

conspire with the American military to pretend that we've been making great strides in Afghanistan, the longest war in American history. Americans are currently mesmerized by their "Peace President" to continue supporting, if not escalating, the most expensive self-deceptive con-job in history. But at least we killed an evil man whose genius was that he was about as observant as an American funny man.

To summarize by paraphrasing George Carlin, the American military involvement in Afghanistan

is a stupid idea, it’s a waste of money, and it’s there for only one reason: to make white people feel safe!. That’s all it’s for. To provide a feeling, an illusion of safety in order to placate the middle class. Because the authorities know they can't make America completely safe from terrorism; too many people have access.

[Photoshop image by Erich Vieth. Image of

George Carlin by Creative Commons; Image of Osama bin Laden, public domain]