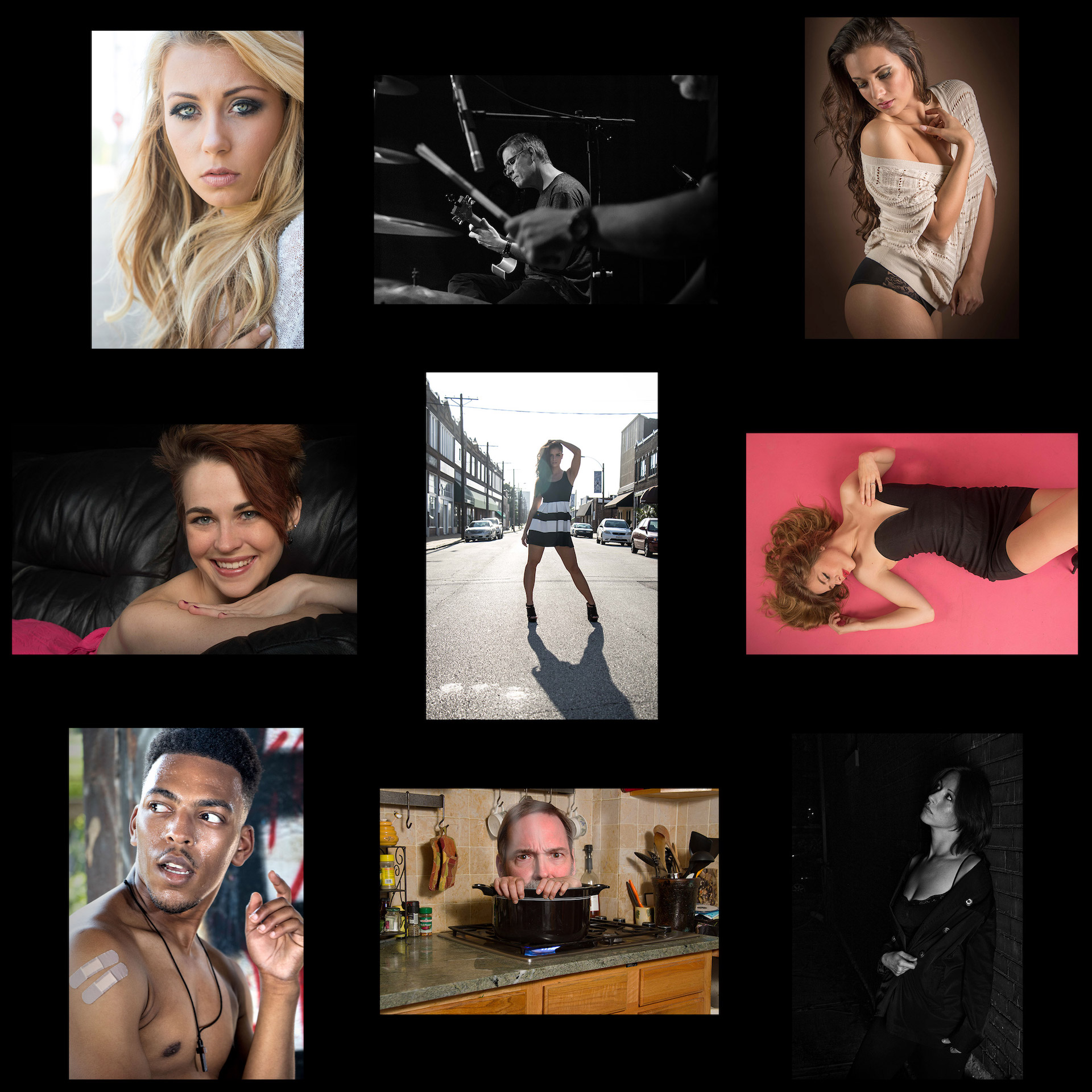

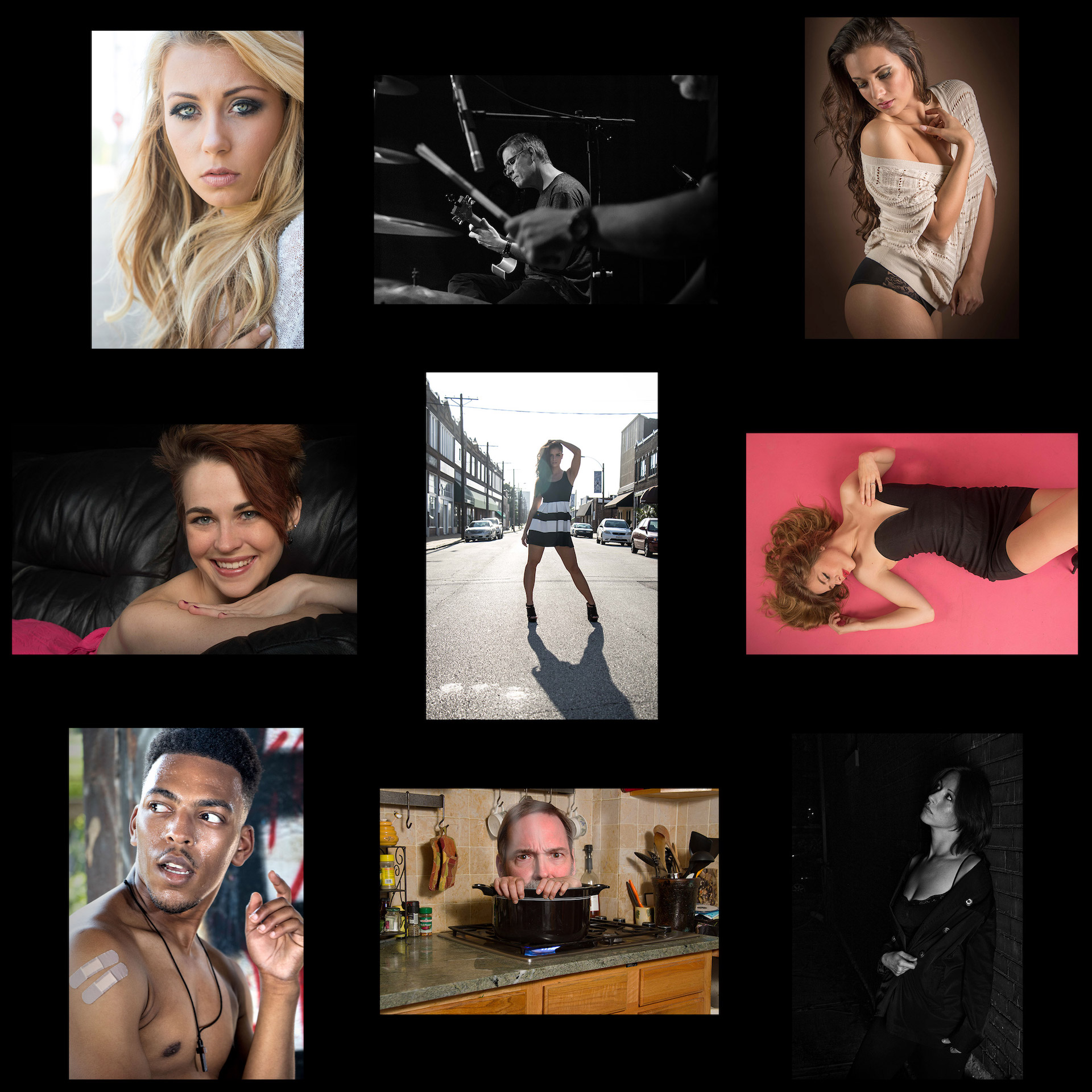

I am guilty of taking more than my fair share of photos. I am guilty of training hard and working hard to try to achieve maximum impact with the photos I take, whether they be portraits or landscapes. Here are some examples of my portraits (you might notice my self-portrait among them):

Here are two of my landscapes from recent years (Rocky Mountain National Park and the Blue Mosque (taken from Hagia Sofia, in Istanbul, Turkey):

As I already mentioned, I'm driven to create photos that have maximum impact, whether it be portraits, landscapes or (beginning this year) my abstract digitized acrylic paintings that I about to begin marketing under the name of Digicrylics. I have been working hard to become the photographer I am, until I was stopped in my tracks--for a few minutes--by Maria Popova's article, "Aesthetic Consumerism and the Violence of Photography: What Susan Sontag Teaches Us about Visual Culture and the Social Web." Here is an excerpt from Popova's article, which comments extensively on Susan Sontag's 1977 book, On Photography:

The aggression Sontag sees in this purposeful manipulation of reality through the idealized photographic image applies even more poignantly to the aggressive self-framing we practice as we portray ourselves pictorially on Facebook, Instagram, and the like:

Images which idealize (like most fashion and animal photography) are no less aggressive than work which makes a virtue of plainness (like class pictures, still lifes of the bleaker sort, and mug shots). There is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera.

Online, thirty-some years after Sontag’s observation, this aggression precipitates a kind of social media violence of self-assertion — a forcible framing of our identity for presentation, for idealization, for currency in an economy of envy.

Even in the 1970s, Sontag was able to see where visual culture was headed, noting that photography had already become “almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing” and had taken on the qualities of a mass art form, meaning most who practice it don’t practice it as an art. Rather, Sontag presages, the photograph became a utility in our cultural power-dynamics:

It is mainly a social rite, a defense against anxiety, and a tool of power.

She goes even further in asserting photography’s inherent violence:

Like a car, a camera is sold as a predatory weapon — one that’s as automated as possible, ready to spring. Popular taste expects an easy, an invisible technology. Manufacturers reassure their customers that taking pictures demands no skill or expert knowledge, that the machine is all-knowing, and responds to the slightest pressure of the will. It’s as simple as turning the ignition key or pulling the trigger. Like guns and cars, cameras are fantasy-machines whose use is addictive.

Popova's article challenges me. What is my purpose when work hard to take high impact photos? I'd like to think that I am merely creating works of art, but is it that simple? I know deep down that I'm doing some expensive signaling, working for a "wow" out of people who view my photos. Can I any longer claim that my obsession with photography is innocent?