What are people (I'm included) concerned about when we talk about "critical race theory" being taught in the classroom, especially K-12? What should we be teaching instead of "CRT"? Greg Lukianoff of FIRE nails it:

What these bills are trying to address doesn’t map directly to the academic definition of critical race theory, which is, in short, an academic school of thought pioneered by Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Mari Matsuda, and Richard Delgado (among others) that holds that social problems, structures, and art should be examined for their racial elements and impact on race, even when they are race-neutral on their face.

As a result, a lot of arguments dismiss the bills by claiming “they don’t teach critical race theory in K-12!”, pointing to the fact that Bell’s work is on few, if any, K-12 syllabi. But that is a refutation of a point no one is actually making.

Like it or not, the acronym “CRT” as commonly used in 2021 doesn’t refer to the foundational texts and authors in the academic movement. It’s a shorthand for certain ideas that have filtered (in reductive forms or not) from CRT thinkers into the mainstream, including in bestselling books like “White Fragility” and “How to Be an Antiracist” — ideas like how relationships between individual white and nonwhite people are those of the oppressor and oppressed, that all white people are consciously or unconsciously racist, that ostensibly raceblind concepts like “meritocracy” are the result of white supremacy, among others.

. . .

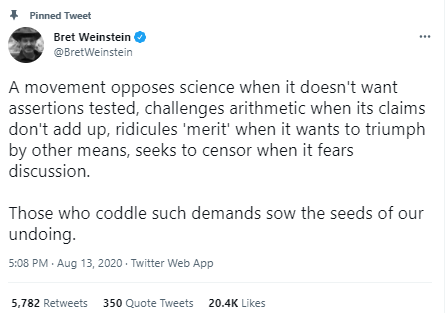

What opponents of “CRT” are getting at is a philosophy that comes directly in conflict with small-L liberalism — and I am among the many Americans who believe the ideals of small-L liberalism are worth defending. What critics of CRT fear is the rise and widespread adoption of a philosophy that relies on genetic essentialism, overgeneralization, guilt by association, what we call in Coddling “The Great Untruth of Us versus Them,” shame and guilt tactics, and deindividuation. This is a formula for reinforcing group difference, undermining the hope of future social cohesion, and returning to the kind of tribal politics of the country in which my father grew up: Yugoslavia.

What should we be doing instead of preaching K-12? Lukianoff has some ideas on that topic too. His article is titled: "The Empowering of the American Mind: We need to fix K-12 education. These 10 principles are a path for reform.". Here are some excerpts from Lukianoff's article:

Principle 1: No compelled speech, thought, or belief.

Principle 2: Respect for individuality, dissent, and the sanctity of conscience.

Principle 3: Foster the broadest possible curiosity, critical thinking skills, and discomfort with certainty.

Principle 4: Demonstrate epistemic humility at all levels of teaching and policymaking.

Principle 5: Foster independence, not moral dependency.

Principle 6: Do not teach children to think in cognitive distortions, e.g.:

Emotional reasoning

Catastrophizing

Overgeneralizing

Dichotomous thinking

Mind-reading

Labeling

Negative filtering

Discounting positives

Blaming

Principle 7: Do not teach the “Three Great Untruths.”

As a society, we are teaching a generation three manifestly bad overarching “untruths”—ideas that contradict both ancient wisdom and modern psychology:

The Untruth of Fragility: What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.

The Untruth of Emotional Reasoning: Always trust your feelings.

The Untruth of Us Versus Them: Life is a battle between good and evil people.

Principle 8: Take student mental health more seriously.

This brings me to the most frustrating thing I’ve seen since publishing the original “Coddling” article. We know anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide are up among young people, and up dramatically. In light of this fact, it is cruel to nevertheless advocate political philosophies that assume:

The majority of students are both oppressors and oppressed due to the color of their skin, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, and/or national origin, and that therefore not only is life rigged against such students, they are also active participants in harming other students;

Words, arguments, and images can be so harmful that students must be shielded from many of them in order to prevent serious psychological harm;

Some students are in a war against oppression, where they don’t have friends but rather “allies”—which implies a conditional, utilitarian arrangement, not a deep and personal bond;

Students must always be on the lookout for slights, as these always mean something much more pernicious than a simple faux pas; and

A single bad joke, dumb comment, or unwise tweet at any moment could, and even should, derail future academic or professional careers.

Principle 9: Don’t reduce complex students to limiting labels.

Sorting students into politically useful categories that involve assigning them character attributes or destinies based on immutable traits circumscribes their potential and hampers their growth. Self-determination is foundational to the American promise and central to our unique national identity. Students must be permitted to decide for themselves how much, or how little, emphasis they wish to place on their race, ethnicity, religion, gender, social class, or economic background.

Principle 10: If it’s broke, fix it.

Be willing to form new institutions that empower students and educate them with the principles of a free, diverse, and pluralistic society. Is this a formula for peace and quiet? No. But free societies aren’t supposed to be particularly quiet. As Justice Robert Jackson gravely warned in 1943, attempts to coerce unanimity of opinion have only resulted in “the unanimity of the graveyard.”