Where would you expect to find sex based differences in career choice most diminished? If you guessed in countries with more wealth and egalitarian culture, you would be wrong. David Geary discusses and interprets the data in his article, “The Nurture of Evolved Sex Differences: Why favorable conditions produce larger sex differences.” In wealthy countries like Norway, increased numbers of women pour into fields that are “people oriented” rather than “thing oriented.” Consider, first, this data:

As reviewed by Schmitt and colleagues [33], sex differences in many aspects of personality, self-esteem, and cognitive and psychological functioning are larger in WEIRD, gender equal countries. For instance, women are generally more cooperative and agreeable than men and men are more Machiavellian than women, on average. These differences are larger in more egalitarian countries. One potential reason is that religious prohibitions and proscriptions increase social cooperation and decrease self-serving behaviors in men and this in turn reduces the sex differences in these areas. The release of these prohibitions enables fuller expression of underlying differences; in this case, a decrease in men’s agreeableness and an increase in their use of Machiavellian social strategies [34].

Occupational segregation also increases in WEIRD, gender equal countries, presumably due to underlying differences in preferences for working with and helping people as contrasted with working with things [35]. Girls’ and women’s greater interest in other people and relationships follows from their greater investment in children and their need to develop BFF (best friends forever) relationships that serve as a source of social and emotional support. Boys’ and men’s greater interest in things likely follows from an evolutionary history of tool making, most of which is done by men.

Stoet and I found there were proportionally (relative to the number of women and men in college) fewer women than men studying and working in non-organic science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, such as computer science, in gender-equal Norway and Finland than in Algeria [36]. In fact, the pattern was found throughout the world, whereby wealth and gender equality were associated with proportionally fewer women entering these fields. Women in less wealthy and less gender equal countries appear to pursue these types of degrees for economic reasons. As economic niches widen and countries become wealthier and more liberal, women (and men) pursue careers that are better aligned with their interests.

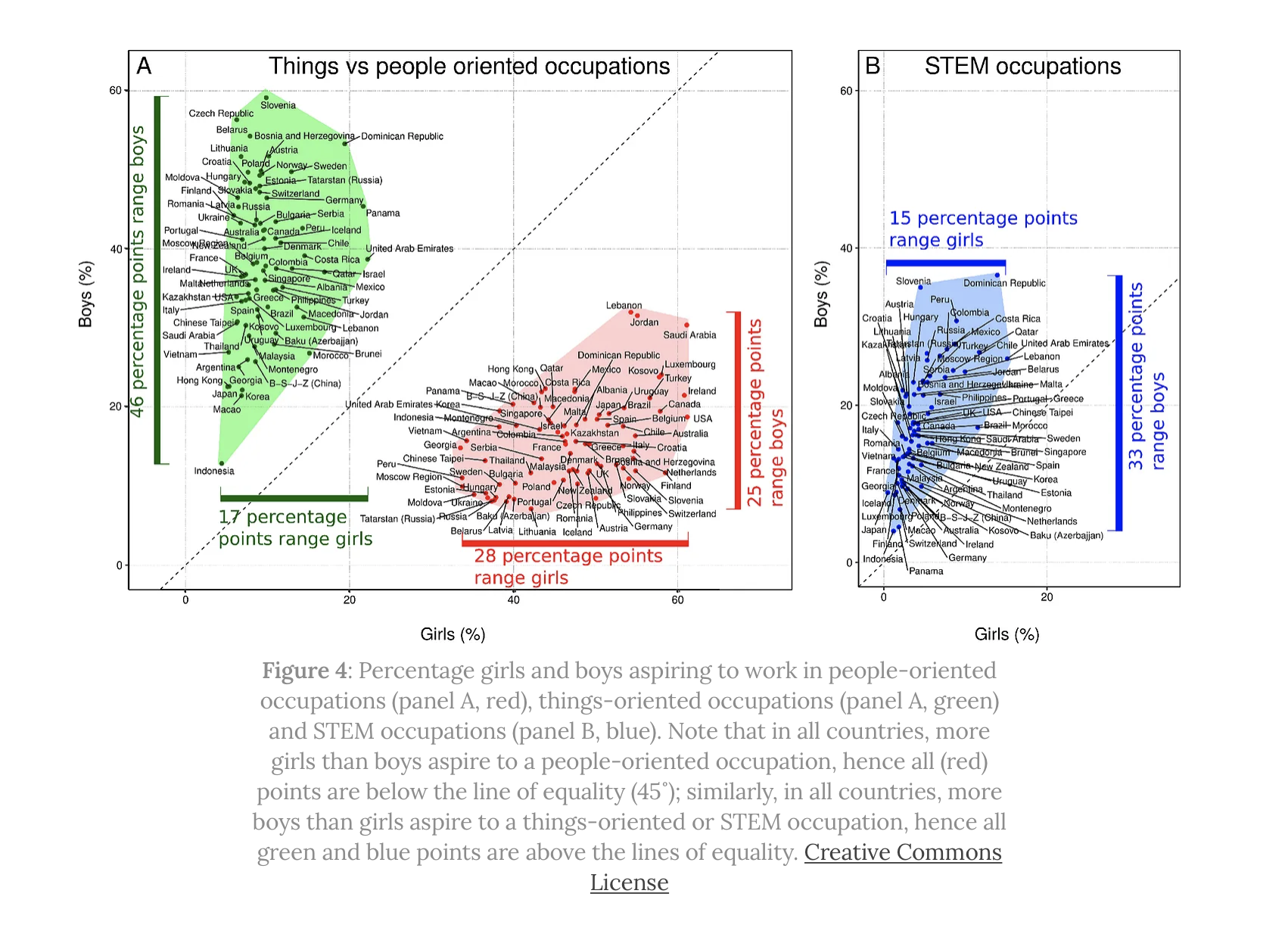

In a follow-up study, we examined the occupational aspirations of nearly half a million adolescents across the 80 developing and developed nations that participated in the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of academic competencies [37]. In this assessment, students were asked, “What kind of job do you expect to have when you are about 30 years old?”, which we termed occupational aspirations. As shown in Figure 4, there was not a single country in which girls were as interested in non-organic STEM fields (e.g., engineering) or blue-collar things-oriented occupations (e.g., carpenter) as were boys, and not a single country in which boys were as interested in people-oriented occupations (e.g., teacher) as were girls. There was nonetheless considerable cross-national variation in the magnitude of these differences.

Across countries (median), there were about 4 boys for every girl aspiring to a things-oriented occupation, and about 3 girls for every boy aspiring to a people-oriented occupation. In keeping with our earlier finding for STEM degrees, for every girl who aspired to enter a things-oriented STEM occupation, there were 5 boys. Again, the ratio was larger in gender-equal countries. In Morocco and the United Arabic Emirates, respectively, there were 1.5 and 1.7 boys for every girl aspiring to a things-oriented STEM occupation, as compared to 4.5 and 4.8 boys to every girl in gender-equal Sweden and Norway.

Geary concludes:

To be sure, social (e.g., prohibition of polygynous marriages) and cultural (e.g., overall wealth, personal liberties) factors can and do have substantive influences on human behavior and well-being. These social and cultural factors can modify the expression of sex differences, but they do not create them de novo.