This is Chapter 28 of my advice to a hypothetical baby. I’m using this website to act out my time-travel fantasy of going back give myself pointers on how to avoid some of Life’s potholes. If I only knew what I now know . . . All of these chapters (soon to be 100) can be found here.

Why do people do the things they do? How can we make sense of all of this talk about what is “moral,” and what is “right” and “wrong.” These are an extremely difficult topics. As we already discussed, however, we need to beware systematizers who scold you to based on their mono-rules of morality. That was the main take-away from the previous chapter.

In this chapter, I’ll briefly discuss three approaches to morality that don’t rely on such simplistic rules. The first of these thinkers is Aristotle, who still has so very much to offer to us almost 2,500 years after he lived. His view of what it means to be virtuous is a holistic set of skills that requires lifelong practice. What a change of pace from the mono-rules of other philosophers. I’ll quote from Nancy Sherman’s book, Fabric of Character pp. 2 – 6:

As a whole, the Aristotelian virtues comprise just and decent ways of living as a social being. Included will be the generosity of benefactor, the bravery of citizen, the goodwill and attentiveness of friends, the temperance of a non-lascivious life. But human perfection, on this view, ranges further, to excellences whose objects are less clearly the weal and woe of others, such as a healthy sense of humor and a wit that bites without malice or anger. In the common vernacular nowadays, the excellences of character cover a gamut that is more than merely moral. Good character–literally, what pertains to ethics—is thus more robust than a notion of goodwill or benevolence, common to many moral theories. The full constellation will also include the excellence of a divine-like contemplative activity, and the best sort of happiness will find a place for the pursuit of pure leisure, whose aim and purpose has little to do with social improvement or welfare. Human perfection thus pushes outwards at both limits to include both the more earthly and the more divine.

But even when we restrict ourselves to the so-called ‘moral’ virtues (e.g. temperance, generosity, and courage), their ultimate basis is considerably broader than that of many alternative conceptions of moral virtue. Emotions as well as reason ground the moral response, and these emotions include the wide sentiments of altruism as much as particular attachments to specific others. . . Pursuing the ends of virtue does not begin with making choices, but with recognizing the circumstances relevant to specific ends. In this sense, character is expressed in what one sees as much as what one does. Knowing how to discern the particulars, Aristotle stresses, is a mark of virtue.

It is not possible to be fully good without having practical wisdom , nor practically wise without having excellence of character . . . Virtuous agents conceive of their well-being as including the well-being of others. It is not simply that they benefit each other, though to do so is both morally appropriate and especially fine. It is that, in addition, they design together a common good. This expands outwards to the polis and to its civic friendships and contracts inwards to the more intimate friendships of one or two. In both cases, the ends of the life become shared, and similarly the resources for promoting it. Horizons are expanded by the point of view of others, arid in the case of intimate relationships, motives are probed, assessed, and redefined.

Aristotle is talking to those of us who live in the real world, recognizing the complexity of the real world and helping us to navigate as best we can. Again, what a change from the mono-rules! This real-world applicability and appreciation of nuance is something Aristotle has in common with the Stoics, which we discussed in Chapter 21.

Here’s another approach, this one from modern times. For a long time, I’ve been almost obsessed that what we think of as moral is, in a real sense, beautiful and what we think of as immoral is ugly. Based on our reactions to situations that are “moral” and “immoral,” there is no possible way that these things are not connected. Such an approach also recognizes that morality is not dictated by any static set of commandments or imperatives. Rather, both morality and art are, at least to some extent, in the eye of the beholder.

Philosopher Mark Johnson has developed an approach to morality based on aesthetics that resonates strongly with me. Here is an excerpt from Johnson’s talk, “Aesthetics of Meaning and Thought.”

I was impressed with Dewey’s account of art as the enactment of the possibilities of meaning in a situation. Art is not a certain narrow area of making. ALL of our experience has aesthetic dimensions. Works of art attract us and we imaginatively engage with them. Works of art opens up possibilities for how to be in the world and how the world can be. It takes a certain sensitivity to what’s being afforded by a situation. It takes a certain kind of cultivated taste, so there’s an educated part of this. It’s a better richer model. Some people would say (1:00:00) that the aesthetic is subjective. I would say “no.” There are subjective dimensions, but aesthetics is about the human capacity to experience and to make meaning. And that’s what we’re about in morality. I was influenced by my dissertation director here. There’s a certain “rightness” in art that is not explicable by rules for the creation of beauty. Morality is like that too. You don’t have definitive rules. You have rules as tools, and you are trying to compose a situation that enriches, liberates meaning, opens up new possibilities and reduces tension. It’s a pretty romantic notion about art, and that’s another debate.

Johnson also wrote a book on this topic, The Aesthetics of Meaning and Thought (2018). Here are a few excerpts:

As a result of our embodied nature, meaning comes to us via patterns, images, concepts, qualities, emotions, and feelings that constitute the basis of our experience, thought, and language. This visceral engagement with meaning, I will argue, is the proper purview of aesthetics. Consequently, aesthetic dimensions shape the very core of our human being.

In this book, I therefore construct an argument for expanding the scope of aesthetics to recognize the central role of body-based meaning in how we understand, reason, and communicate. The arts are thus regarded as instances of particularly deep and rich enactments of meaning, and so they give us profound insight into our general processes of meaning-making that underlie our conceptual systems and our cultural institutions and practices. Humans are homo aestheticus—creatures of the flesh, who live, think, and act by virtue of the aesthetic dimensions of experience and understanding.

It would be nice if we had absolute, certain, eternal knowledge of our world. We do not, because our world is forever changing and our perspective is limited and partial. It would be nice if we had absolute, certain, eternal knowledge of how we should live as moral creatures. We do not, because the very nature of our situated, embodied engagement with our world and other people gives rise to a plurality of values and ways of ordering our lives. We are not, to quote Dewey, “little gods” possessed of pure reason.

. . .

Our involvement with morally significant narratives can change the way we understand situations, feel toward others, and see them as vulnerable creatures worthy of our care and respect. Taking moral imagination seriously therefore often requires us to abandon certain assumptions about morality that are deeply rooted in our moral traditions. We have to give up the idea that our moral categories and values are given to us from a completed and fixed moral universe. We therefore have to give up the idea that the right moral decision is given in advance, just waiting for us to discover it and apply it correctly to our present situation. We have to move beyond the view that morality is a system of rationally derived principles that conjointly define our moral responsibilities. We have to recognize that moral deliberation is a trying out, via imaginative projection, of ways our world might be. Moral imagination is our chief resource for enhancing the quality of life for ourselves, others, and our world in general.

. . .

Moral imagination is thus not merely a single faculty for applying ethical principles to concrete situations. It is, rather, a person’s way of being in and transforming his or her world by means of the ability to imagine how situations might develop toward greater harmony, cooperation, freedom, growth of meaning, and envisioning of moral ideals. As such, it is not a deductive process of bringing cases under rules or principles, but more like an artistic process for creatively remaking our world in search of enriched meaning and fulfillment for all concerned. It should be judged by a person’s sensitivity, care, and wisdom in envisioning new ways of being in the world that harmonize competing values and open up new relations and possibilities for enhanced meaning and well-being.

. . . .

What we are is embodied creatures whose understanding and values emerge from our ongoing transactions with our physical, interpersonal, and cultural environments. That makes our morality perspectival, fallible, and subject to change over time. An appreciation of our nature as embodied finite creatures is the premise on which this claim about the limitations of our moral understanding is based.

Aristotle has convinced me that it is based upon experience and practice and Mark Johnson has convinced me that the way we determine what is moral is based upon an aesthetic sense.

Each of us is a consortium of trillions of cells that somehow—seemingly miraculously—act in coordinated fashion as an individual organism. At this organism-level, we are attracted to some things (e.g., sugar) and repulsed from others (e.g., snakes). A big part of who we are is determined by the stuff out of which we are made, our biology. Evolutionary psychologists have made a strong case that natural selection not only formed our natural features, such as arms and livers, but also shaped many of our behavioral routines, such as urge to flee dangers and our intense compulsions to eat and have sex. How do we know what to do next? Antonio Damasio posits that through our biology and life experience, we assemble a emotion-weighted map of attractions and repulsion that guides us. See Chapter 11. In his book, Moral Animal, Robert Wright eloquently wrote that emotions are “evolutions executioners.”

But back to that question that simply won’t go away: What should we do next? Yes, we are “moved” through our emotions. We might move toward some of those things that attract us, but we certainly move away from those things that our map forbids. Can we get any more specific about what we are moved to move toward and what to avoid? I’m going to set aside physical survival skills and I’m going to focus on the things we think of as being in the realm of the “moral” (though these two things overlap extensively). We act in order to survive, and this plays out in some predictable and understandable ways, according to Jonathan Haidt, who has written extensively about this topic in his book, The Righteous Mind. We previously discussed Haidt’s theory of social intuitionism, the idea that the huge intuitive Elephant mostly runs the show and that our little Rider makes shit up (doing things like barking out simplistic “moral rules”) to justify whatever the elephant wants. Haidt carefully points out that the elephant is filled with intuitions, not emotions (emotions interweave inextricably with cognition). See Chapter 11.

Haidt makes a strong case based upon his real-world research that which most of us think of as the realm of “moral” is severely impoverished. Yes, we all are concerned about being kind to each other (care/harm). Yes, we are concerned about equality (fairness). These two things are critically important for all humans, at least within that group of people with whom each of us identifies–our in-group. Inversely (and this is something that Martian anthropologists find absolutely stunningly insane), we treat people outside of our in-group miserably, despicably.

Early in Haidt’s career, he asked whether other things besides care/harm and fairness belonged in the realm of “the moral.” Based on his research, he concluded that morality is like the sense of taste. We have several types of receptors on the tongue and he identified a set of five taste receptors in “the righteous mind”: care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and sanctity. Based on further research, he eventually added a sixth foundation, liberty/oppression. At p. 368, Haidt writes:

If you take home one souvenir from this part of the tour, may I suggest that it be a suspicion of moral monists. Beware of anyone who insists that there is one true morality for all people, times, and places-particularly if that morality is founded upon a single moral foundation. Human societies are complex; their needs and challenges are variable. Our minds contain a toolbox of psychological systems, including the six moral foundations, which can be used to meet those challenges and construct effective moral communities. You don’t need to use all six, and there may be certain organizations or subcultures that can thrive with just one. But anyone who tells you that all societies, in all eras, should be using one particular moral matrix, resting on one particular configuration of moral foundations, is a fundamentalist of one sort or another.

Haidt traces each of his foundations to survival. He didn’t figure these out with armchair psychology. He spent years comparing cultures to see what moral foundations they had in common.

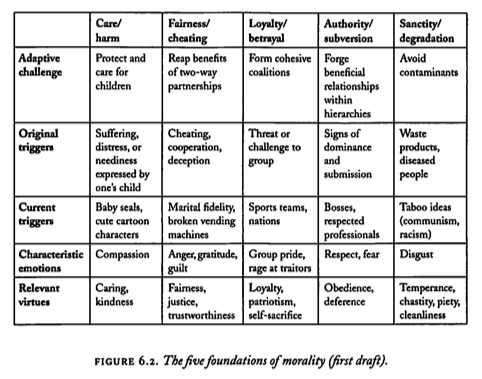

We created it by identifying the adaptive challenges of social life that evolutionary psychologists frequently wrote about and then connecting those challenges to virtues that are found in some form in many cultures. Five adaptive challenges stood out most clearly: caring for vulnerable children, forming partnerships with non-kin to reap the benefits of reciprocity, forming coalitions to compete with other coalitions, negotiating status hierarchies, and keeping oneself and one’s kin free from parasites and pathogens, which spread quickly when people live in close proximity to each other.

See the following chart:

As noted above, Haidt added a sixth moral foundation:

The Liberty/oppression foundation, I propose, evolved in response to the adaptive challenge of living in small groups with individuals who would, if given the chance, dominate, bully, and constrain others. The original triggers therefore include signs of attempted domination. Anything that suggests the aggressive, controlling behavior of an alpha male (or female) can trigger this form of righteous anger, which is sometimes called reactance. . . .Liberty/oppression foundation, which makes people notice and resent any sign of attempted domination. It triggers an urge to band together to resist or overthrow bullies and tyrants. This foundation supports the egalitarianism and antiauthoritarianism of the left, as well as the don’t tread-on-me and give-me-liberty antigovernment anger of libertarians and some conservatives. We modified the Fairness foundation to make it focus more strongly on proportionality. The Fairness foundation begins with the psychology of reciprocal altruism, but its duties expanded once humans created gossiping and punitive moral communities. Most people have a deep intuitive concern for the law of karma-they want to see cheaters punished and good citizens rewarded in proportion to their deeds.

Haidt’s research is compelling evidence that mono-theories of morality do not explain what it means to be “moral.” His Moral Foundations Theory explains

one of the great puzzles that has preoccupied Democrats in recent years: Why do rural and working-class Americans generally vote Republican when it is the Democratic Party that wants to redistribute money more evenly? Democrats often say that Republicans have duped these people into voting against their economic self-interest. (That was the thesis of the popular 2004 book What’s the Matter with Kansas?). But from the perspective of Moral Foundations Theory, rural and working-class voters were in fact voting for their moral interests. They don’t want to eat at The True Taste restaurant, and they don’t want their nation to devote itself primarily to the care of victims and the pursuit of social justice. Until Democrats understand the Durkheimian vision of society and the difference between a six-foundation morality and a three-foundation morality, they will not understand what makes people vote Republican.

For more on Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory, see here, here, here and here.