Hello again, Hypothetical Baby! I’m back to offer you yet another chapter with a simple lesson. As you grow up, people will question you about some of the decisions you make on “moral.” Issues. By the way, “Moral” is an ambiguous word. We tend to pull it out most often when we are talking about sex, death and distribution of food and the other things you need to stay alive. That reminds me. Someday we will have some good discussions about sex that will consist mostly of letting you watch selected David Attenborough Nature Videos featuring animal sex. You’ll find that most human talk about sex is confusing and unhelpful except to let you know that most other people are as awkward discussing it as you will be. I’ll give you a one sentence preview. Bank on this: human animal sex is a lot like the sex of other mammals, even though it does not much resemble the exotic sex of snails.

Before we go further on moral decision making, here’s a short reminder that I’m trying to teach you things that I did not know while I was growing up. I learned these lessons the hard way. You can find links to all of these (soon to be 100) lessons here.

Now, back to your moral decision-making. After people challenge why you made a particular “moral” decision, you will try to give reasons and words will actually come out of your mouth, but much of the time (to quote “My Cousin Vinny,” it will be a bunch of bullshit.

Jonathan Haidt has shown that, for the most part, we don’t make moral decisions using our ability to reason methodically. Moral decision-making is not like math; there is no metric for making moral decisions. Nor does our ability to decide moral issues make use of emotions (which are intricately tied up with our sense of reason, as we discussed in Chapter 11). Most of our moral decision-making is intuitive. Based on sophisticated and entertaining experiments, Haidt has shown that our moral judgements are instantaneous and based on intuitions (akin to what Daniel Kahneman describes as thinking fast). After you’ve made your quick and dirty moral decision, you will employ your slow difficult thinking to concoct excuses that you will publicly present as “reasons” for your decisions.

You are probably surprised. You are probably thinking that important decisions should be made with the best equipment human animals have, their ability to calculate and weigh factors and churn the issue in the “highest centers” of the brain, the parts of your brain that you will use to write philosophy papers. Sorry, but it doesn’t happen that way, even though most people in most situations will claim that they are deliberate and methodical whenever they make moral decisions. Moral intuitions are similar to our intuitions regarding optical illusions. We are often helpless to have intuitions other than the one’s we are having. Intuitions can be strong, indeed!

Here are a few long excerpts from Haidt’s excellent book, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. In a nutshell, this is Haidt’s “Social Intuitionist Model”:

The mind is divided, like a rider on an elephant, and the rider’s job is to serve the elephant.

In The Happiness Hypothesis, I called [reason and intuition] the rider (controlled processes, including “reasoning-why”) and the elephant (automatic processes, including emotion, intuition, and all forms of “seeing-that”). I chose an elephant rather than a horse because elephants are so much bigger–and smarter-than horses. Automatic processes run the human mind, just as they have been running animal minds for 500 million years, so they’re very good at what they do, like software that has been improved through thousands of product cycles. When human beings evolved the capacity for language and reasoning at some point in the last million years, the brain did not rewire itself to hand over the reins to a new and inexperienced charioteer. Rather, the rider (language-based reasoning) evolved because it did something useful for the elephant.

The rider can do several useful things. It can see further into the future (because we can examine alternative scenarios in our heads) and therefore it can help the elephant make better decisions in the present. It can learn new skills and master new technologies, which can be deployed to help the elephant reach its goals and sidestep disasters. And, most important, the rider acts as the spokesman for the elephant, even though it doesn’t necessarily know what the elephant is really thinking. The rider is skilled at fabricating post hoc explanations for whatever the elephant has just done, and it is good at finding reasons to justify whatever the elephant wants to do next. Once human beings developed language and began to use it to gossip about each other, it became extremely valuable for elephants to carry around on their backs a full-time public relations firm.

At another point in this same book, Haidt adds,

The rider is our conscious reasoningthe stream of words and images of which we are fully aware. The elephant is the other 99 percent of mental processes-the ones that occur outside of awareness but that actually govern most of our behavior.

Alternatively, you can think about the tiny Rider as an attorney, who drums up excuses for doing whatever the elephant craves. According to Haidt, “Reason is the servant of the intuitions. The rider was put there in the first place to serve the elephant.”

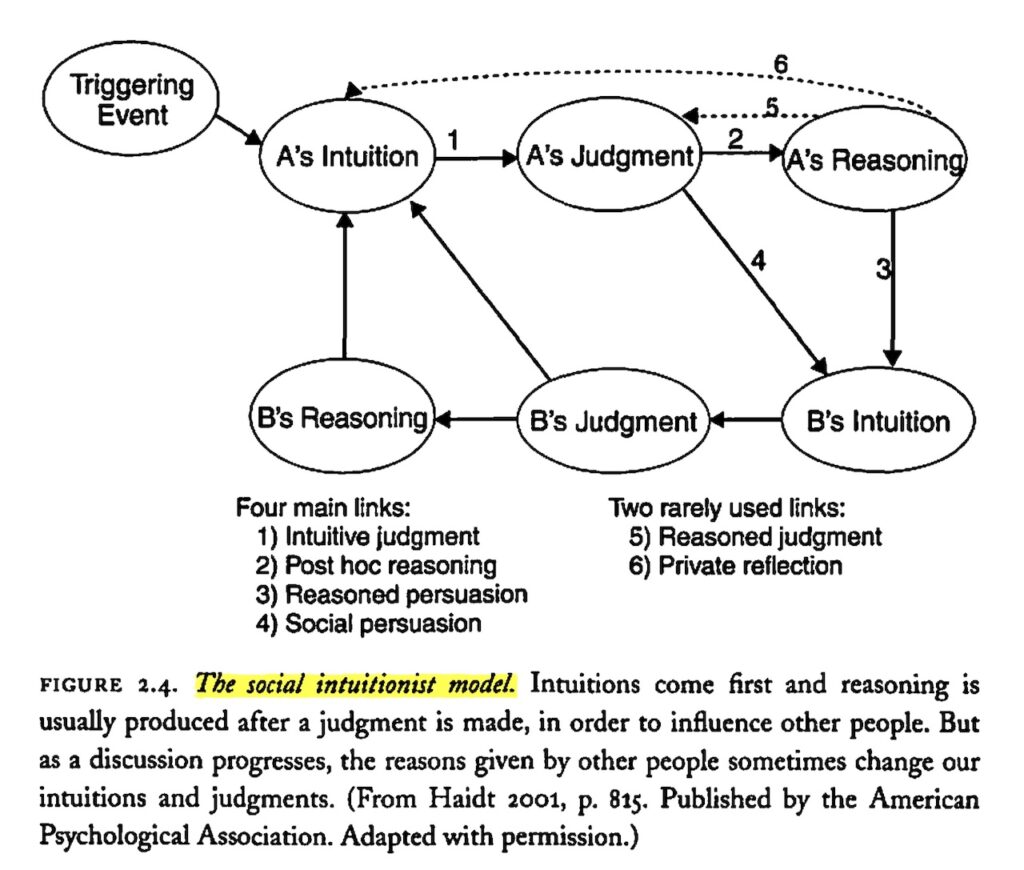

Note this diagram of Haidt’s Social Intuitionist Model:

Haidt’s model emphasizes

the social nature of moral judgment. Moral talk serves a variety of strategic purposes such as managing your reputation, building alliances, and recruiting bystanders to support your side in the disputes that are so common in daily life. . . . We make our first judgments rapidly, and we are dreadful at seeking out evidence that might disconfirm those initial judgments. Yet friends can do for us what we cannot do for ourselves: they can challenge us, giving us reasons and arguments (link 3) that sometimes trigger new intuitions, thereby making it possible for us to change our minds. We occasionally do this when mulling a problem by ourselves, suddenly seeing things in a new light or from a new perspective (to use two visual metaphors). Link 6 in the model represents this process of private reflection. The line is dotted because this process doesn’t seem to happen very often. For most of us, it’s not every day or even every month that we change our mind about a moral issue without any prompting from anyone else.

Haidt does not completely reject our ability to reason through moral dilemmas. He is rejecting the “worship of reasoning. ” His conclusion is heavily based on the research pertaining to motivated reasoning and the confirmation bias, which show (as David Hume argued) “reasoning is extremely effective as a servant, but rather ineffective as a tool for discovering the truth, at least when carried out by individuals.” Intuitions, which are much more common and flexible than emotions, are not the whole story for Haidt in his theory, which he call “The Social Intuitionist Model,” but they’re are most of the story. Haidt say, “They’re where the action is.” Accordingly, if one seeks social change, you’ve got to get to work on the intuitions.

As you’ll grow up this will be obvious to you. You will not change anyone’s mind on politics and religion (at least not on the spot) by arguing and logic. You will need to first cultivate a relationship and develop an environment of trust before you will make any headway.

I’m going to have a lot more to say about the Elephant, the Rider and the loud squawky public relations firm that we carry around all day. That that is it for now!