For many years, I thought of “ADHD” and “ADD” as dysfunctional conditions with which other people struggled, not me. Discussion of these conditions brought back vivid grade school memories of several bright and energetic boys struggling to sit still in their desks for seven hours, while nuns scolded and belittled them. I was fully aware of the social stigma that came with a diagnosis of ADHD. At the same time, I have long been aware that many successful people have been diagnosed with ADHD. I’ve long been convinced that, to some degree, their ADHD traits fueled their success.

Before my divorce in 2014, my wife Anne (in our 18th year of marriage) accused me needing treatment “because of ADHD,” explaining that I was “ruining the marriage.” She had been reading a website called ADHD and Marriage. She insisted that I should see a doctor to get medication for my “problem.” She told me that I was a bad listener. She told me these things repeatedly. It didn’t help that these concerns were hurled at me, not gently broached, but I now understand her frustration better.

An ADHD diagnosis also seemed ridiculous because I had never before been told I exhibited ADHD symptoms. No other human being ever raised a concern about ADHD until Anne proclaimed her diagnosis in black and white. Nor did any instances of ADHD seem apparent in any of my close relatives.

I resented these sole-cause accusations because I saw our marriage to be much more complex than that and far more nuanced. Also, I liked who I was and saw myself as high functioning. I have always been upbeat. I enjoy many activities and I’m fairly good at various things, including my legal career, writing and composing music. Also (as I reminded my wife), I was capable of sitting in front of a computer screen for twelve hours per day writing complex appellate briefs. I have received awards for my brief writing. Fellow lawyers (and opposing lawyers) have often expressed that they like working with me. On a regular basis, more than a few of my friends tell me that I am an extremely attentive listener.

After the divorce in 2014, I became increasingly intrigued about ADHD. I started reading various articles and books about ADHD. From this informal research, I became convinced that many of the qualities associated with the ADHD mind are things that describe me well. In December, 2020, Anne died suddenly causing me to do a lot of thinking about a lot of things, including our marriage, including the role ADHD might have played in our struggles over the last few years of our marriage.

More icing on the cake: a counselor has gotten to know me well over the past few months. He recently blurted out: “You are ADHD from top to bottom.” Hmmm. That I am indisputably high-functioning (unlike many people who receive the diagnosis) doesn’t rule out ADHD, but it explains why I pushed back when a diagnosis was hurled at me. I’ve thought further about my ability to writing for many hours at a stretch? After the divorce learned that hyper-focusing is something that some people with ADHD diagnoses do well.

The above paragraphs are a bit awkward for me to re-read because my purpose is here is not to tout my accomplishments. It is not my purpose to drag my marital struggles into the public, post-mortem. My purpose is to show the reasons for my initial confusion and to set the stage to explain something fascinating I’ve recently learned about my way of processing the world. Perhaps my journey might help others.

Recently I asked the following question to my previous wife of 11 years (I’ve been married twice): Did you ever think of me as having ADHD traits? I received this response:

Hi, ADHD candidate. “No” to thinking you had ADHD. You did have a pattern of embracing different interests: music, photography, cartooning, philosophy, writing, bicycling. So I guess you were shifting focus, not weekly but maybe sometimes monthly? I always attributed it to your existential ticking clock . . .

This confirmed my suspicion. I don’t know anyone who thought of the younger version of me as having any ADHD tendencies. That’s where a new book became extremely interesting to me. The book, titled ADHD 2.0: New Science and Essential Strategies for Thriving with Distraction–from Childhood through Adulthood, was written by Edward Hallowell, M.D. and John Ratey, M.D., two men who had introduced the general public to attention deficit disorder back in 1994 with an earlier book titled Driven to Distraction. They note at the outset that they are both diagnosed with ADHD. Spoiler alert for the remainder of this article: The fact that one doesn’t have a diagnosis of ADHD isn’t the end of the story.

In first few pages of their new book, Hallowell and Ratey note that

Most people, even now, don’t understand the power, magnitude, and complexity of this condition. Nor do they know the tremendous advances in understanding and treatment that have been made in recent years. They know only caricatures and sound bites of incorrect or incomplete information.

They indicate that people don’t grow out of ADHD, even though they seem to. Instead, they learn to compensate. ADHD “can crop up for the first time in adulthood. This often happens when the demands of life exceed the person’s ability to deal with them.” (p. xiv). They give an example of such adult-onset ADHD: someone starting medical school. They mention that ADHD occurs in at least 5-10% of the population. It is often passed from parent to child: “It is actually recognized as one of the most heritable conditions in the behavioral sciences.”

Hallowell and Ratey mention that ADHD can be “a scourge, an unremitting, lifelong ordeal” that can lead to suicide and addictions and that “having ADHD costs a person nearly thirteen years of life, on average.” Those with ADHD have “the power of a Ferrari engine but with bicycle-strength brakes. It’s the mismatch of engine power to braking capability that causes the problems. Strengthening one’s brakes is the name of the game.”

The authors note the central challenge for one struggling with ADHD: boredom.

Boredom is our kryptonite. The second that we experience boredom— which you might think of as a lack of stimulation— we reflexively, instantaneously, automatically and without conscious thought seek stimulation. We don’t care what it is, we just have to address the mental emergency–the brain pain—that boredom sets off.

ADHD can destroy promising careers. It can also be “a powerful asset, a gift.”

It is also highly treatable with medications, the “calming and focusing power of exercise” and “finding the right kind of difficult,” the work or activity that is best suited to a mind that needs to be active. It can cause pain and suffering in many. . . . If mastered, it brings out talents you can neither teach nor buy. It is often the lifeblood of creativity and artistic talents. It is a driver of ingenuity and iterative thinking. It can be your special strength or your child’s, even a bona fide superpower.

(p. xvii).

This “superpower” of seemingly boundless energy, creativity and optimism, comes to life in disordered environments, situations that make many neurotypical people anxious:

[R]isk taking and irrational thinking go hand in hand with ADHD behavior. We like irrational. We’re at home in uncertainty. We’re at ease where others are anxious. We’re relaxed not knowing where we are or what direction we’re headed in.

Those who know me personally will nod as they read these words. Yes, this very much describes me. For many years, I’ve tried to express to others that being me is not easy. It is often like pushing on the gas and brakes at the same time. I constantly struggle to listen well, in that my mind goes dashing off to separately consider the first few sentences spoken by others, missing the next 30 seconds – thank goodness for my mental buffer, which often allows me to stitch conversations back together on the fly. Hence, I am an excellent listener, except when I take extended high-energy excursions into my own head. This is a double-edged sword, allowing me to bring new non-obvious observations to the conversation, but only if my excursion is quick. If I dally in my excursions, though, this can cause me to miss things that naturally attentive listeners methodically hear in real time.

All of the above presents a situation Churchill might term “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” The problem is that I did not exhibit indication of ADHD until well into adulthood. There was no trace of it even when I was under the considerable stress of attending law school or in the early stages of my legal career. No one suggested that I look into “ADHD” back then. Nor (as I sit back and reminisce) did have such a monkey mind or drive forward with new projects like I do now. Those “ADHD” aspects of me weren’t apparent until within the past two decades. It intrigues me that these qualities seemed to emerge more and more as I took on high-stakes complex litigation over the past two decades. I often worked 50-60 hours per week to handle these complex high profile cases. Trying lawsuits is one of the more stressful things that humans do. Did that stressful work over such a long period somehow rewire my brain?

I now have a potential explanation, and it is a vast topic. “VAST” as in “variable attention stimulus trait.” Hallowell and Ratey explain that there is a functional (environmentally induced) equivalent of ADHD they call “VAST”:

Modern life compels these changes by forcing our brains to process exponentially more data points than ever before in human history, dramatically more than we did prior to the era of the Internet, smartphones, and social media. The hardwiring of our brains has not changed— as far as we know, although some experts do suspect that our hardwiring is changing— but in our efforts to adapt to the speeding up of life and the projectile spewing of data splattering onto our brains all the time, we’ve had to develop new, often rather antisocial habits in order to cope. These habits have come together to create something we now call VAST: the variable attention stimulus trait.

Whether you have true ADHD or its environmentally induced cousin, VAST, it’s important to detoxify the label and focus on the inherent positives. To be clear, we don’t want you to deny there is a downside to what you are going through, but we want you also to identify the upside.

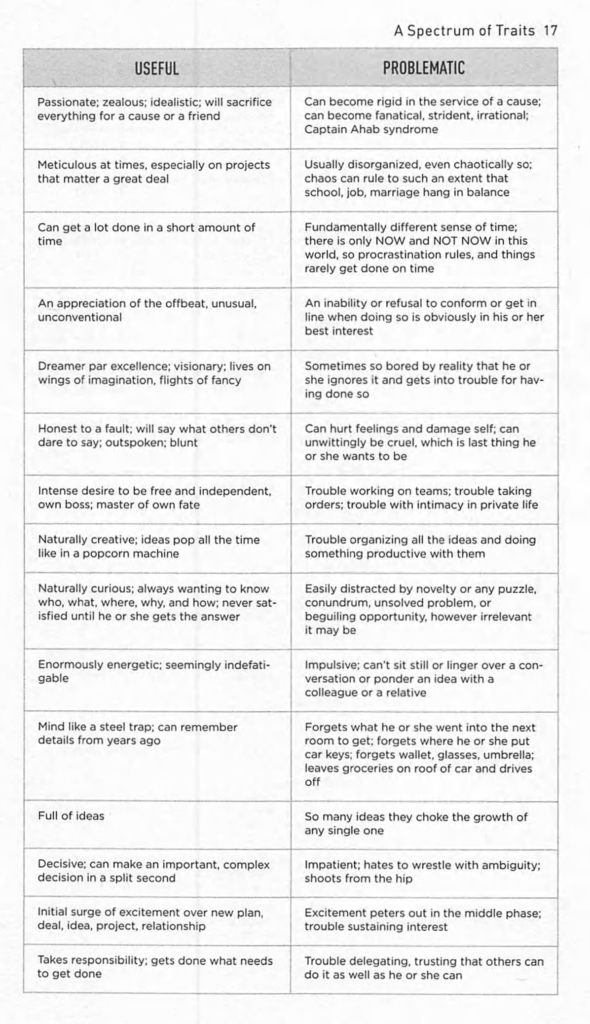

The authors summarize many of those characteristics of VAST in a two page chart—I’m reproducing one page of those characteristics in order to substantiate many of the points I’ve been making in this article. And as you can see, each of these traits can be employed as either a useful ability, but also a detriment.

Thanks to books like ADHD 2.0, I don’t see my condition (whether it be ADHD or VAST) as a dysfunction, but as a different way of processing the world, with lots of pluses and some minuses. I see it as a bucket of perceptual and engagement strategies I employ in my journey through life. I’m glad that these strategies are becoming more conscious. Being mindful allows me to use these strategies where appropriate and try to tamp them down when they aren’t furthering my goals.

These strategies can sometimes supercharge me, but these “powers” must be used carefully. I now realize that keeping up with me when I’m in overdrive can be difficult and annoying for many people, but, notably, not for people with ADHD—we joyously toss gasoline on each others’ fires. However one might label it, I embrace the positives of my way of thinking and it has served me well for decades. I don’t want to tamp down my fire. But neither do I want to be the bull in the social china shop. I need to monitor my listening skills. I need to repeatedly ask myself about whether that latest new bright shiny thing should really the top priority this hour. I am more mindful about pausing when I suddenly change gears, asking myself whether this is something I should be doing in the context of all of my various stated goals. On the other hand, I increasingly have fun watching myself get excited when I have the opportunity to make sense of new disorienting situations that makes others anxious—there is no better cure to my Achilles Heel of boredom.

Keeping a functional balance is now a prime concern, day in and day out. I often remind myself of the benefits of bleeding off the excess energy with exercise. Doing this makes me a better post-exercise listener and reader. When a project is due, I can now plainly see that I am most effective when I protect myself with turned-off phone and closed doors, armed with task lists and promises (to myself) that I will allow myself to play in bigger spaces once the necessary work is done. And the way I “play” is often through art, whether that be writing, photography or composing music. I’ve learned that it is important that I schedule both my work time and play time as an incentive to completing tasks that I have declared to be my priorities (helpful suggestions here, courtesy of Laura Vanderkam).

All of this is making more sense to me these days, even though I still have no formal diagnosis. So in the absence of that formal diagnosis, I’m putting my chips on VAST, and I’ll proceed accordingly.

If you’ve followed this article all the way here, to the bottom, I’m assuming that you might be one of these 5-10% or perhaps you intimately know such a person. hope that these ideas have given you some useful insight.

Erich, compelling insight here. I am just learning of VAST via a podcast that I happened onto earlier this week. I was particularly interested in Dr. Hallowell’s differentiation between ADHD and VAST, insomuch as they are, in fact, the same set of conditions but he has a new way of naming and addressing in a person-first way.

I read your article as if to possibly suggest that VAST – (Variable Attention Stimulus) Trait may be a high-functioning variant of ADHD. I think I would be careful to not identify them differently from one another but rather to help re-educate the general public and help reduce stigma that is often a direct residual effect of misunderstanding. Dr. Hallowell suggests that the name Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is simply wrong on its face. It is certainly not a deficit situation, quite the opposite really. And we are hoping to move away completely from words like disorder for further obvious reasons. Especially since there is more anecdotal evidence over time suggesting that this is most often a hereditary trait that can be tied to previous family diagnosis very frequently.

I have signed up for your blog in hopes of reading your reply to this. All the best.

Thanks, John. I had no intention of casting either of these (VAST and ADHD) as derogatory. In my mind, they are simply different styles of cognition. Employed knowledgeably and with care, both of these are “super powers.” I mentioned that society at large (and my ex-wife in particular) have used the term ADHD as an insult, as a personal defect, an ailment. Nothing in my article indicates that I share that view.

Hi Erich from Loutraki, Greece,

I am now writing a 220+ thousand words novel over an artist with V.A.S.T. whose existence I am proud to claim.

I appreciated your article here, Erich. I practiced law as both a trial and appellate attorney in the Colorado public defender and conflict counsel system for 11 years, finally closing up shop two years ago. I knew as far back as sophomore year of high school (1996) that I had some learning differences and a strong tendency to procrastinate, but I was smart enough that I could always pull off As on school papers and tests in spite of these, though by the end of high school and beginning of college I was struggling mightily with alcoholism and severe depression. I never received a formal ADHD diagnosis, but suspected it off and on over the last 25 years. My legal career was tortured, I now see largely as the result of my ADHD symptoms (distractibility, impulsivity) and because the work often involved disturbing and violent fact patterns I rarely could enter that hyper-focused state you describe as aiding your complex brief-writing, and so I perennially found myself completing briefs the day or night before they were due, often filing requests for more time, sometimes filing a brief electronically at 11:59 pm on the due date. I was also divorced from a wife of 9 years and am now in the midst of the end of my subsequent 8-year relationship, the latter very clearly linked and the former almost certainly linked to my ADHD, the financial instability resulting from my struggles in “professional” jobs, and the brooding, ruminating DMN trap that Drs. Hallowell and Ratey describe in ADHD 2.0. I wish a lot of things had been different, but I also share your sentiment that I like who I am, and I have many strengths, intellectual curiosity, the capacity to forge close and invigorating connections with like-minded people, an interest in creative work, creative writing in particular, also cooking, drawing, and music, and I take very good care of my body, exercise daily, and I’m quite fit and healthy. So on balance, I wouldn’t change who I am if I could, and I can’t anyway, however I hope with some of the insights I’m gathering from books like ADHD 2.0 that in time I will learn to harness the power and mitigate the drawbacks of my ADHD more effectively. Long story short, thank you for your words.

Alex: Thank you so very much for sharing your reactions to my article and connecting those thought to your personal challenges. I know that there are a lot of us out there. Like you, I’m still learning how to make use of my skillsets and to tamp down my distractibility. There are many moments where I notice the problem and I stop, breathe, and laugh at myself. But there are also many days when I impulsively get in over my head. I really appreciate your insights. I wish you the best in your journey forward! Erich