Let’s see. It’s the weekend. If I want to spend time with others tonight, what should I do? Where should I go? Who would like to spend time with me?

Here’s a seemingly unrelated question: Who is more popular in most parts of American society?

a) An animated people who engages in banter about pop culture, sports, TV and movies with their like-minded friends, where loud partying and drinking alcohol are significant parts of the gathering?

b) A person who enjoys intense discussions about science and other intellectual pursuits with like-minded people in quiet places, where partying and small talk are not significant aspects of the gathering?

Today, I stumbled upon an article in Forbes that raises concerns about how those who love to study science are sometimes ostracized by others. This article by Ethan Siegel is titled, “Your Glorified Ignorance Wasn’t Cool Then, And Your Scientific Illiteracy Isn’t Cool Now.” Here is an excerpt:

All across the country, you can see how the seeds of it develop from a very young age. When children raise their hands in class because they know the answer, their classmates hurl the familiar insults of “nerd,” “geek,” “dork,” or “know-it-all” at them. The highest-achieving students — the gifted kids, the ones who get straight As, or the ones placed into advanced classes — are often ostracized, bullied, beat up, or worse.

The social lessons we learn early on are very simple: if you want to be part of the cool crowd, you can’t appear too exceptional. You can’t be too knowledgeable, too academically successful, or too smart. Someone who knows more, is more successful, or smarter than you is often seen as a threat, and so we glorify ignorance as the de facto normal position.

In my experience, it’s not usually such a clear distinction as in A or B above, and there are many styles of socializing. I’m focusing on these because am a “B” type person who found myself trapped in a few too many “A” environments over the past year. I should also make clear that I have no problem with drinking, only drunkenness, and a lot of nerdy people admittedly do enjoy alcoholic drinks. Further, many people, nerdy or not, like to discuss the science stories they find in news sources that don’t specialize in science. These things are often interesting, even when not explored in depth.

The real division lies here: Some of us take science and other intellectual pursuits much more seriously than others. Some of us read challenging and detailed science publications, and we contemplate science spontaneously, when waiting in line or walking down the street; we cannot turn it off. Digging to deeper levels inspires us to learn even more, and this hard-earned knowledge often bears fruit in the form of connections to many other aspects of our lives. Digging deeply often enables us to challenge the way we conceive of ourselves and others. Most people who socialize, however, get exhausted, bored, tired of discussing these topics and would rather have “fun.”

Having an enthusiastic love of intellectual pursuits can be a social problem. Exploring science issues in depth requires a different type of conversation than the conversation one typical finds in most social gatherings. In most social gatherings, the participants want to have “fun” in a way that is inconsistent a sustained focus on higher level intellectual topics. Geeky types tend to be introverts like me; Susan Cain points to research showing that introverts are notorious for avoiding chit chat. In “fun” gatherings, people like me are lucky to get in more than a sentence or two, even on a challenging topic, at which time the conversation tends to move on to other topics that are more “fun.” Over many decades, I’ve heard this sort of comment over and over: “Gee . . . are you always this serious?” This is despite the fact that for many of us, discussing these challenging topics is fun, anywhere and everywhere.

Merely discussing science isn’t automatically a good thing, of course. It is irritating to be in the presence of a science know-it-all or in the presence of anyone who tends to hog the conversation, no matter how smart they are. Science discussions only work best where there is a deep commitment to learning from each other, accompanied by a sense of humility and a willingness to be self-critical. Ethan Siegel comments:

All of the solutions that require learning, incorporating new information, changing our minds, or re-evaluating our prior positions in the face of new evidence have something in common: they take effort. They require us to admit our own limitations; they require humility. And they require a willingness to abandon our preconceptions when the evidence demands that we do.

In my experience, mixing those wanting to have good ole’ fun with those who long for invigorating intellectual conversation is a train wreck. Such a mismatches are frustrating things for all participants Those who want to have “fun” don’t want to feel like they are at a college seminar. Those who are excited by intellectual ideas feel rejected, ignored and isolated by those who are less committed to learning at gatherings that are supposed to be fun. The nerdy sorts of people seek social connection, but the ideas that they are most excited about make them unwelcome (except in tiny doses) in many social situations. It’s as if they come to “fun” gatherings smelling like skunks.

What is the solution for the nerds and geeks who feel rejected? There don’t appear to be many ready-made gatherings for designed for these people on weekend evenings, which is when many people socialize. Nor are Sunday mornings a popular time for intellectual group discussion, because Sunday is mostly the time for religion, not science. There might be other opportunities, for instance through some Meetups. Another way to connect with like-minded others is to attend seminars and conferences on your favorite subject, whether locally or far away. I do this often and often enjoy the socializing as much as the learning.

One of my new interests is rock hounding. I recently discovered that there is a monthly Saturday evening meeting of rock hounds at a nearby university. I’m looking forward to this sort of fun in a few weeks.

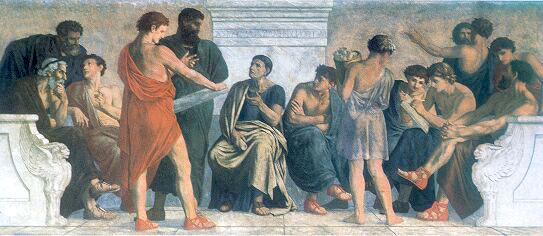

I’m also in the process of assembling a gathering of my own, which I call a symposium tongue in cheek. It will be a monthly gathering of hand-selected people who are excited to have an invigorating exchange of the sorts of ideas we all find interesting. There will be drinks and snacks, but there won’t be any party games and there won’t be much discussion about the latest new TV show on Netflix. We’ll see how it goes. It is my hope that this “symposium” will serve as a monthly refuge for people who think intense learning in a social setting is one of the best ways to have fun.

I am definitely a B) person. I love hanging with smart, informed people.

Erich, stop hounding rocks! What did they ever do to you anyway???

Those rocks like living in my house rather than being stuck underground in the dark. I tell them that they are pretty every day and they giggle.