There is much talk of “sustainability” these days, but I don’t think very many people have considered what that truly means. “Sustainable” has become synonymous with “green”, which in our hyper-consumerist American society has transformed into “buy something“. Understandable, perhaps, but it’s deadly wrong. The World English dictionary defines “sustainable” as “2. (of economic development, energy sources, etc) capable of being maintained at a steady level without exhausting natural resources or causing severe ecological damage”, which seems to me to be a pretty good definition of what the word really means, as opposed to what people think it means.

Environmentalist and author Derrick Jensen explains the problem of sustainability in his book Endgame Vol. I: The problem of civilization.

“Any social system based on the use of nonrenewable resources is by definition unsustainable…The hope of those who wish to perpetuate this culture is something called “resource substitution,” whereby as one resource is depleted another is substituted for it… Of course, on a finite planet this merely puts off the inevitable, ignores the damage caused in the meantime, and begs the question of what will be left of life when the last substitution has been made. Question: When oil runs out, what resource will be substituted in order to keep the industrial economy running? Unstated premises: a) equally effective substitutes exist; b) we want to keep the industrial economy running; and c) keeping it running is worth more to us (or rather to those who make the decisions) than the human and nonhuman lives destroyed by the extraction, processing, and utilization of this resource.

…

“Another way to put all of this is that any group of beings… who take more from their surroundings than they give back will, obviously, deplete their surroundings, after which they will either have to move, or the population will crash… This culture — Western Civilization– has been depleting its surroundings for six thousand years, beginning in the Middle East and expanding now to the entire planet. Why else do you think this culture has to continually expand? And why else, coincident with this, do you think it has developed a rhetoric– a series of stories that teach us how to live– making plain not only the necessity but desirability and even morality of continued expansion– causing us to boldly go where no man has gone before– as a premise so fundamental as to become invisible? Cities, the defining feature of civilization, have always relied on taking resources from the surrounding countryside, meaning, first, that no city has ever been or ever will be sustainable on its own, and second, that in order to continue their ceaseless expansion, cities must ceaselessly expand the areas they must ceaselessly hyperexploit. I’m sure you can see the problems this presents and the endpoint it must reach on a finite planet. If you cannot or will not see these problems, then I wish you the best of luck in your career in politics or business.” (p. 36-37)

Jensen argues that we are now in the endgame of human civilization, and that human survival is literally at stake. But right now you’re probably saying to yourself, “I’ve heard all of this before, and nothing bad has happened.” We could accuse Jensen of being another Malthusian nutcase, but more and more scientists and experts are warning of similar danger. Malthus warned that human population was expanding faster than it could increase production of food, but he failed to anticipate the advances that came as a part of the Industrial Revolution. Malthusian warnings now commonly mocked as wrong, but what if he were simply early? Andrew Leonard at Salon.com writes:

“And yet his dystopian vision that humanity’s lot, our inescapable fate, will be grinding, desperate poverty, lives on. Down for more than 200 years, but not yet out, because there’s always a get-out-of-jail-free card for Malthus: Just wait.

Just wait until the technological wellsprings of innovation run dry, when even the most advanced genetic modification technologies can no longer boost food yields. Just wait until peak oil puts an end to the age of cheap energy, until the oceans are overfished and the atmosphere is choked with carbon dioxide. Just wait until Chinese and Indians and Brazilians consume with the same unsustainable abandon as Americans. Malthus isn’t wrong — he just isn’t right … yet.”

Similarly infamous was the wager between economist Julian Simon and ecologist Paul Ehrlich. The wager was that the price of a basket of metals would be higher in ten years time than when they made the bet in 1980. Ehrlich lost that bet, and it entered into our cultural memory as proof that the free markets solve all of our problems and that environmentalists are the modern Chicken Little. Energy blogger Gregor MacDonald explains why that understanding is mistaken:

“…once you start moving the 10 year bracket forward from 1980 then Ehrlich, who bet on scarcity and lost, starts to win. Indeed, the winner of the wager was the beneficiary of timing, not insight. But leave it to economists to convert ephemeral conditions into permanent ones. While it’s true that both the price signal and technology can bring forth more supply of resources, often at lower costs, this is only true up to a limit. Once those limits are reached, as we have seen in global Copper and also Oil for example, then better technology might be able to create more supply on a nominal basis, but not at a lower price, and not in real terms.”

In other words, although technology and the free market can allow us to find oil in places we couldn’t before (like say, under a mile of water in the Gulf of Mexico), or even to exploit a greater percentage of the oil that we find, they cannot make up for the fact that oil is ultimately a finite resource. The time-frame to generate new supplies is millions of years. Global oil discoveries peaked in the 1960’s and we have used more oil than we’ve discovered since the 1980’s, so our situation becomes more precarious by the day.

It would be a mistake to focus simply on oil, though. The truth is, we face an enormous and interconnected set of problems without any easy solutions. Rather than simply Peak Oil, we are really dealing with what Richard Heinberg calls “Peak Everything“. We are living beyond our means, ecologically speaking, and one day that bill will come due. Unfortunately, we keep racking up the bills, faster than ever:

Think tank the New Economics Foundation (NEF) look at how much food, fuel and other resources are consumed by humans every year. They then compare it to how much the world can provide without threatening the ability of important ecosystems like oceans and rainforests to recover.

This year the moment we start eating into nature’s capital or ‘Earth Overshoot Day’ will fall on 21st August, a full month earlier than last year, when resources were used up by 23rd September.

Climate change is affecting both humans and other species, threatening all of our collective survival. The U.N. is among the most strident in sounding the warning. Ahmed Djoghlaf, the secretary-general of the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity, argues “What we are seeing today is a total disaster… if current levels [of destruction] go on, we will reach a tipping point very soon. The future of the planet now depends on governments taking action in the next few years.” The Guardian continues:

According to the UN Environment Programme, the Earth is in the midst of a mass extinction of life. Scientists estimate that 150-200 species of plant, insect, bird and mammal become extinct every 24 hours. This is nearly 1,000 times the “natural” or “background” rate and, say many biologists, is greater than anything the world has experienced since the vanishing of the dinosaurs nearly 65m years ago. Around 15% of mammal species and 11% of bird species are classified as threatened with extinction.

Almost 1,000 times the background rate of extinction, and accelerating. Far worse,these extinctions and declines are starting to affect species that form the foundation of the food chain. If these species go, there will be no turning back. The Independent reports:

The microscopic plants that support all life in the oceans are dying off at a dramatic rate, according to a study that has documented for the first time a disturbing and unprecedented change at the base of the marine food web.

Scientists have discovered that the phytoplankton of the oceans has declined by about 40 per cent over the past century, with much of the loss occurring since the 1950s. They believe the change is linked with rising sea temperatures and global warming.

…

“Phytoplankton is the fuel on which marine ecosystems run. A decline of phytoplankton affects everything up the food chain, including humans,” Dr Boyce said.

A meta-analysis of the existing data on the health of the world’s oceans came to a very similar conclusion last year.

Comparing the oceans to human lungs, [study lead-author Ove] Hoegh-Guldberg said

“… the findings have enormous implications for mankind, particularly if the trend continues … Quite plainly, the Earth cannot do without its ocean. This study, however, shows worrying signs of ill health. It’s as if the Earth has been smoking two packs of cigarettes a day!”

…Hoegh-Guldberg does not keep anyone in suspense over the consequences of unchecked climate change.

“This is further evidence that we are well on the way to the next great extinction event.”

Not merely on the way, the extinction event has been happening for some time. 21% of all mammals are at risk for extinction, as are 30% of amphibians. Some scientists have called the modern age the “anthropocene“, and are warning that the scale of extinctions could be similar to the five other acknowledged epochs in Earth’s history. Species are now vanishing faster than they have at any other time in the past 65 million years:

Researchers now recognise five earlier cataclysmic events in the earth’s prehistory when most species on the planet died out, the last being the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event of 65 million years ago, which may have been caused by a giant meteorite striking the earth, and which saw the disappearance of the dinosaurs.

But the rate at which species are now disappearing makes many biologists consider we are living in a sixth major extinction comparable in scale to the others – except that this one has been caused by humans. In essence, we are driving plants and animals over the abyss faster than new species can evolve.

Consider some other recent headlines:

- One-fifth of the world’s vertebrate species at risk of extinction

- Tigers could be extinct in 12 years

- One in five plant species faces extinction

- Census of marine life: large animals in danger of dying out

- And if you like oysters, better eat them while you still can: Oysters disappearing worldwide, now “functionally extinct”

Culturing oysters- one attempt to mitigate failing natural harvests. Image via Wikipedia (commons)

This is coming at a time when it’s already increasingly difficult to feed the people that we already have, not to mention the billions on the way. The impacts of climate change, global price speculation, increasing population, the shift to a Western diet, limited water supplies, etc… are already causing prices to spike and people to go hungry. From 2005-2008 world food prices were up 217%. The challenge is ongoing, in another 20 years we will need to increase our food production by 50% just to keep up. The diversion of cropland from agriculture to the production of biofuels as a result of the arrival of peak oil means that we are already deciding that it’s more important to power our extravagant lifestyles than it is to make sure that people are fed. Not only that, but the demand for biofuels is so strong, it’s accelerating deforestation and a host of other environmental problems. Even wealthy and fully-developed countries like Britain and Australia are starting to ask how they are going to feed themselves. Corporations and governments around the world are grappling with the same question, and buying up key commodities like potash. The Telegraph explains:

However, this month has also seen news reports on escalating wheat and coffee prices due to bad weather and poor harvests. Then on August 19 came the headline “Australian mining giant launches hostile $40 billion takeover bid for world’s largest potash supplier”. It is not immediately apparent what we’re talking about here, but this is City champagne bar speak for “world runs out of food”. This really is news about food that consumers should be fearful of.

There is a finite quantity of naturally occurring potash, or potassium carbonate, in the Earth’s crust. You can manufacture it by burning down forests of broad leaf trees – let’s not go there. Digging it out of the ground is the agri-business-preferred option. Meanwhile, to produce the nitrogen for fertiliser you need to burn an awful lot of – er – crude oil. Yep, the world is going to look like a perforated airflow golf ball by the time we’ve finished with it.

Every government needs to pay attention to what is happening. It is the opportunity for a debate about what is the right way forward and it may well be that if, at this juncture, we choose the wrong food policy, there will be no going back.

See what I mean about peak-everything? But hey, who cares, right? That new I-pad sure looks spiffy.

Others are also warning of the interconnected and synergistic nature of the threats facing humanity:

But in his chilling book The Coming Famine, journalist and science writer Julian Cribb warns we are headed towards global food shortages in the next 40 years because of scarcities of water, good land, energy, nutrients, technology, fish and, significantly, stable climates. You can add to that population growth, consumer demand and protectionist trade policies.

“The coming famine is also complex, because it is driven not by one or two, or even half a dozen factors but rather by the confluence of many large and profoundly intractable causes that tend to amplify one another,” Cribb writes. “This means that it cannot be easily remedied by ‘silver bullets’ in the form of technology, subsidies, or single-country policy changes, because of the synergetic character of the things that power it.”

The world is running out of farmland. Advanced farming depends entirely on fossil fuels likely to become scarce, supplies of nutrients for farming have peaked and fresh water resources are finite. With global warming, up to half the planet faces regular drought by the end of the century. Storms and the kinds of floods that have devastated Pakistan are tipped to become more frequent and intense.

The same basic factors are at play in each of these cases: the relentlessly increasing population, and the profligate use of resources. We assume that because technology has always saved us in the past, that it will inevitably do so in the future. Unfortunately, we’re starting to see the contours of some very unyielding limits. Not to mention that our so-called solutions have in some cases created other, unforeseen problems. Like the fertilizers that powered the Green Revolution which are now causing dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico the size of Massachusetts, compounding the problem of feeding ourselves.

Erich here at Dangerous Intersection has called for a more open debate on the population problem, and he’s hardly alone. The Independent wrote earlier this year:

Misery, what misery? You can of course imagine the political class arguing that scientists have consistently got it wrong about overpopulation. But the next 40 years are going to be very different to the previous 40 years, and many scientists fear that there will indeed be extreme misery to come if the world does not take population more seriously.

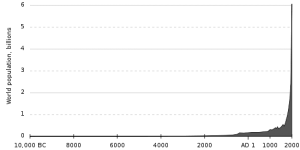

The facts speak for themselves. The UN estimates that the global population will rise from 6.8 billion in 2009 to 8.3 billion by 2030, with much of the increase in the poorest countries, notably sub-Saharan Africa, which is set for a 51 per cent increase in the same period – four times that of the UK.

World food production will have to increase by 50 per cent to meet rising demand; water availability will have to increase by 30 per cent; and global energy demands by 50 per cent. Politicians may think that science and technology will provide what is needed, as it has done in the past at a cost to the environment, but many scientists are not so sure.

But, somehow, everything seems to be relatively normal as we look around. Ecosystems are collapsing around us, but by most objective measures, more people are doing well than at any time in the past. This is known as the “environmental paradox”, and researchers are struggling to understand why. In discussing a new study, Scientific American lays out the case:

For decades, apocalyptic environmentalists (and others) have warned of humanity’s imminent doom, largely as a result of our unsustainable use of and impact upon the natural systems of the planet. After all, the most recent comprehensive assessment of so-called ecosystem services—benefits provided for free by the natural world, such as clean water and air—found that 60 percent of them are declining.

Yet, at the exact same time, humanity has never been better. Our numbers continue to swell, life expectancy is on the rise, child mortality is declining, and the rising tide of economic growth is lifting most boats.

The study that Scientific American is talking about is available for a limited time here, after which it will be behind a paywall. The authors of the study examine 4 hypotheses to explain the divergence between the health of the planet and the health of it’s global population.

The four hypotheses are:

1. Critical dimensions of human well-being have not been captured adequately, and human well-being is actually declining. Measures of well-being that suggest it has increased are wrong or incomplete.2. Provisioning ecosystem services, such as food production, are most significant for human well-being; therefore, if food production per capita increases, human well-being will also increase, regardless of declines in other services.

3. Technology and social innovation have decoupled human well-being from the state of ecosystems to the extent that human well-being is now less dependent on ecosystem services.

4. There is a time lag after ecosystem service degradation before human well-being is negatively affected. Loss of human well-being caused by current declines in services has therefore not yet occurred to a measurable extent.

The authors dismiss the first hypothesis, as the data in this area is fairly clear and convincing. Society as a whole seems to have adopted the third hypothesis as unalloyed truth. One could make a pretty good case for the second hypothesis, but personally I think that the fourth is the most likely. None of these are mutually exclusive, so it would be more accurate to say that it’s probably some combination of the second and fourth hypotheses. In other words, because we’ve been able to generate an increasing amount of food per-capita, we’ve been blind to damage in other areas. That damage will catch up with us at some point in the future, but has not yet. For reasons explained in this post, sometimes “tipping points” are reached which we are unable to see coming, after which we are unable to regain equilibrium until we reach a new, stable state of ecology, usually at a much-impoverished level from the previous steady state. A similar dynamic can be observed in the economic arena, as experts are telling us that the millions of newly unemployed persons since the crisis began in late 2008 are symptomatic of structural changes to the economy, meaning that the high levels of unemployment are the “new normal” for the forseeable future. (Note also that under the “new normal” link, the authors at the Brookings Institute attribute a major part of the economic crisis to excessive levels of consumption, which “depended increasingly on unsustainable increases in household debt and declines in personal savings”– a clear parallel to our ecological situation.)

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, some very credible and brilliant scientists are sounding the alarm, some in surprising ways. Stephen Hawking is warning that we must find a way to abandon this planet if humanity is to survive:

The man who helped eradicate smallpox, Professor-emeritus Frank Fenner, has a similar warning:

We humans are about to be wiped out in a few decades. The grandchildren of many of us will not live to old age.

Hear it from Frank Fenner, emeritus professor of microbiology at the Australian National University and the man who helped eradicate smallpox.“Homo sapiens will become extinct, perhaps within 100 years,” he told The Australian this week.

“It’s an irreversible situation.” Blame global warming.

So, to round it back up to where we started, “sustainable” has become the latest buzzword, but stop and think about what it really means. Sustainability is like pregnancy– there is no partway. Either we have a sustainable civilization, or we don’t. It’s clear that we don’t, so what are the implications of that? Either we get sustainable, or we risk collapse and extinction. The only debate left is over the time-frame.

If one thing is clear, it’s that we cannot depend on government action to take the necessary steps. Politicians are generally incapable of seeing beyond the next election cycle, and sometimes not even that far. The U.S. National Intelligence Council (which, according to its website, seeks “to provide policymakers with the best, unvarnished, and unbiased information—regardless of whether analytic judgments conform to US policy”) released a report in late 2008 which makes this crystal clear in its analysis of the converging threats facing us (emphasis mine):

A switch from use of arable land for food to fuel crops provides a limited solution and could exacerbate both the energy and food situations. Climatically, rainfall anomalies and constricted seasonal flows of snow and glacial melts are aggravating water scarcities, harming agriculture in many parts of the globe. Energy and climate dynamics also combine to amplify a number of other ills such as health problems, agricultural losses to pests, and storm damage. The greatest danger may arise from the convergence and interaction of many stresses simultaneously. Such a complex and unprecedented syndrome of problems could overload decisionmakers, making it difficult for them to take actions in time to enhance good outcomes or avoid bad ones. (p.41)

But don’t worry. Robert Laughlin, the co-recipient of the 1997 Nobel prize for Physics, explains that the earth will be just fine, even if we will not:

Humans can unquestionably do damage persisting for geologic time if you count their contribution to biodiversity loss. A considerable amount of evidence shows that humans are causing what biologists call the “sixth mass extinction,” an allusion to the five previous cases in the fossil record where huge numbers of species died out mysteriously in a flash of geologic time. A popular, and plausible, explanation for the last of these events, the one when the dinosaurs disappeared, is that an asteroid 10 kilometers in diameter, traveling 15 kilometers per second, struck the earth and exploded with the power of a million 100-megaton hydrogen warheads. The damage that human activity presently inflicts, many say, is comparable to this. Extinctions, unlike carbon dioxide excesses, are permanent. The earth didn’t replace the dinosaurs after they died, notwithstanding the improved weather conditions and 20,000 ages of Moses to make repairs. It just moved on and became something different than it had been before.

A very balanced and thoughtful piece, Brynn. Suggest you cut the slaving and boost the philosophizing!

While I would not go as far as Frank Fenner, it is quite likely there will be some sort of global population collapse in the mid-century, especially if people start fighting over food and scarce resources and if climate change kicks in as predicted. While excellent in other respects, democratic governments are by definition unable to make the necessary change to cope witht the confluence of issues that is coming down, because they rely on popular support which, broadly, does not comprehend these issues. It would be a great shame were democracy to fail its greatest test, but it is probable in view of the large number of noodles who are now trying to do their best to ensure it does.

More at issue, even, is whether we deserve our arrogantly self-chosen 18th century title Homo sapiens sapiens. My own suggestion is that we reclassify the species (Homo sapiens stultus) until such time as it actually proves it can survive the conditions it has created. That includes adopting "sustainable" systems in all walks of life and cutting the current $1.5 trillion global arms budget to a level consistent with other terrestrial species that have survived a lot longer than ourselves.

Julian-

Thanks for coming by and honoring my post with a comment. I haven't read your book yet, though I intend to do so soon.

I think "extinction" may indeed be too strong of a term, but the value lies in attempting to prod a slumbering citizenry into some kind of awareness of the crises we are facing.

I also respect and concur with your calls to decrease global arms spending, starting with the USA, the undisputed champion of "defense" spending. There are so many other areas calling out for investment to mitigate the problems facing us. Thanks for all you do!

What makes you think the citizenry is "slumbering"? Because they don't display your level of zeal or intellectual prowess on this matter? That may be a big assumption…

I would think that the 'citizenry' is very concerned about all these issues, but people put things into priority: feed the kids first, don't lose the job, replace the wiper blades on the Chevy… If environmentalism or 'green' influences those choices somewhere along the way, then people think they've done what they can.

I postulate that:

1. People are more aware than you think

2. People don't have viable reasonable choices in front of them (i.e. how many people should walk to work, but realistically cannot afford the extra 30 minutes it would take each way)

3. Like skin cells that get replaced every 2-3 weeks, people's consumption patterns are the most realistic way to a sustainable culture. No one will throw out their washer/dryer for a more green version just to get on Al Gore's good side, but the next time it comes to buy a replacement, they'll go with the sustainable one (as long as the price is within spitting distance). Sustainability is a journey, not cold-turkey.

4. If #3 is true (seems to be true), then the economic substitution model actually holds water: keep pushing on solar technology, and eventually those roof-top panels _will_ be cheaper than the coal-fired utility. Voila! Solar will explode (substitution). Electric cars may (may!) soon be cheaper than gas. If/when that happens (only a matter of time now), then watch substitution happen very very quickly.

I am equally skeptical of some of the assumptions in your well-written post:

– innovation only accelerates, it doesn't "run dry" (your quote from Salon)

– food security in developing countries is a concern, but there are enormous efficiencies to be gained by ending subsidies in the developed world first. In short, let Africa get the investment (not hand outs) it needs, and watch food production grow considerably.

Dave-

Thanks for your comments, and I appreciate the kind words.

I make a number of assumptions about what's on America's mind these days, mostly based on news coverage or "buzz". Since it's obviously impractical to survey each American, I mostly rely on proxies, like the news feed, what is big on sites like Reddit, or what gets discussed around the water cooler. I'll grant you that most American's do seem to want to be "green", but again, I don't think most people have an understand about what that really means. Recycling will not save us. Buying a new washing machine (whether immediately or as an eventual replacement) will not save us.

And that's the real problem: the scale of our proposed solutions are completely inadequate to deal with the array of devastating problems facing us. Looking at my Google News feed, the top story is about Lindsey Lohan arriving for a court date, followed by some news about the Green Bay Packers, and then the fact that Gabrielle Giffords spoke today. All are of supreme importance, I'm sure, but what's not atop the news? The potential extinction of the human race, or the major extinction event we are currently living in, or the fact that today we have to feed 219,000 more people that we had to feed yesterday. Tomorrow, we'll have to do it again. And the day after that. Or that the major banks are profiting by speculating on food, and that people are dying as a result. Or the fact that there's a major pharmaceutical shortage, here and now, and people are dying as a result. Or that one-in-three families is Hackney, UK is too poor to heat their homes. Many of these issues are impacting those of us in the developed world, it's not solely a problem facing the developing nations.

It has nothing to do with zeal or intellectual prowess, all I'm asking for is a sense of urgency in proportion to the scale of the problems. Again, buying something will not solve the problem. In fact, our cultural default of buying something might <span style="font-style: italic; font-weight: bold;">BE</span> the problem.

You say that "People don’t have viable reasonable choices in front of them." But what are viable, reasonable choices? Presumably you mean choices that don't cause too much individual discomfort. Yet in the meantime, the world is burning. If we take the accumulated knowledge from the scientists and others studying these issues that I have presented, then what could possibly be more important than immediately beginning to figure out solutions? I'll grant you the top priority facing the "citizenry": make sure the kids get fed. I say we do it. But the catch is, we have to keep on doing it, and I think we should do it for everyone, not just the people that can afford it.

Your reliance on substitution assumes that the existing infrastructure will last until the substitution is viable, but what if you're wrong? What if an economic collapse rocks the first world (again), combined with an inability to increase oil production? Where does the infrastructure or financing or energy come from in the meantime to roll out the panacea of solar panels and electric cars? And the power grid is strained to capacity in many places already, where is the additional electricity to come from? Electricity is not a source of energy, it's a storage and transmission mechanism. How do we manufacture these solar panels and electric cars in a resource and finance-constrained world?

You say that "innovation only accelerates", but I don't believe that to be true. It may be true in high-tech fields where computing power doubles on a decreasing timeframe, but I'm not sure that concept is transferable to things like food production, or water, or arable land. The Green Revolution was our last major breakthrough in food production, and that was the 70's. What's next? GM crops are already proving to be a disappointment. The World Bank reports:

You'll get no argument from me that ending subsidies should happen immediately. But you're wrong to limit questions of food security to developing countries only, as you'll note from my post even wealthy and fully-developed countries like the U.K. and Australia are starting to wonder how to feed their citizens. And Africa's getting plenty of investment, but sadly, it's the exploitative kind (again). Countries (and agri-business giants) around the world are snapping up farmland in Africa and other less-developed countries as a hedge against the day when their own water or land base is exhausted.

Brynn,

Wow– what a well thought-out response, thanks for that. And when I said 'intellectual prowess', I meant it as a sincere compliment– not many people will go to the length you do in their posts (I know I don't).

If I may, I think we have a difference of opinion not on goals but on methodologies. You seem to be advocating a sustainable planet by wanting to raise awareness among the masses, focusing on the news stories coming out, and disseminating information. Great. I would take a different tack: people have enough information (or think they do), and really won't do anything until it's economically sensible for them to do so. The dishwasher replacement is just my example of that: people may or may not know about being more sustainable, but until it comes time to replace the dishwasher, they'll really not _act_ in one way or the other.

Perhaps both methods are needed: raise awareness so people know their options out there and are more aware of the consequences of certain actions (don't eat certain fish); simultaneously, continue to pursue technological improvements that bring better energy and food options online.

Finally– to your last point on technology advances in grain production: I would grant you that GM may not be all it was promised, and that grain yields may taper off– I would equally submit that there is still plenty of inefficiencies in the distribution chain to still boost yields (to the table) overall.

All right, folks. Let's refill our coffee mugs and meet in the break room in five.

We need to break this one down, figure out what we're talking about here, really focus.

No doubt about it, we are living in an age of extreme cognitive dissonance.

On one hand, there are large numbers of eminent scientists and thinkers who believe, as environmentalist Derrick Jensen argues, "that we are now in the endgame of human civilization, and that human survival is literally at stake."(to quote the above article).

Yikes.

And microbiologist Frank Fenner, also quoted above, is even more pessimistic: “Homo sapiens will become extinct, perhaps within 100 years,” he said. “It’s an irreversible situation.”

Yikes. And yikes again.

On the other hand, you have the entire leadership of the Republican Party, as well as a large swath of the American public, who believe there is no problem at all, in fact, that everything is fine. President Obama pandered to this idea by neglecting to mention global warming in his recent State of the Union address.

If anything, these folks believe, we need way fewer environmental regulations and that Americans should be encouraged to pump *more* carbon-dioxide into the atmosphere, as U.S. Rep. John Shimkus, R-Illinois, has testified memorably on a number of occasions.

Consequently, we get to see the absurd spectacle of U.S. Rep. Fred Upton, R-Mich., the chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, declaring war on the EPA and saying it has no business regulating greenhouse gases. You have many of the top leaders in Congress and the business community overtly hostile to any mention of the idea that global warming/climate change presents any sort of major problem at all.

It's become obvious to me that the United States government will do nothing meaningful to combat climate change for many years to come, if ever. And if the U.S. refuses to budge, then it's unlikely the rest of the world will do so, either. And since we're talking about a series of vicious feedback loops here (as more arctic ice melts, the ocean heats up further, which melts more ice, etc.,) the price for continued inaction grows scarier and scarier.

So we're all screwed, right?

Let's sip on our coffee a few moments while we ponder this possibility.

Maybe we are screwed. We need to wrap our brains around that distinct possibility.

Just like we, as adults, have accepted the idea that we and the ones we love will one day die, so, too, we must accept the possibility that our race, because of the greed and arrogance of our most powerful members, have set the stage for our extinction and the extinction of many other species.

OK, now let's step back and consider another possibility: things are not *quite* that dire and that there is still time to make a difference. In which case, it would seem incumbent on those of us who do believe we are in deep trouble to try to change the minds of those who do not.

How to do this?

For starters, we need a new public relations campaign. We need to put a face on global warming and the price of inaction. The attempts to do this so far have failed miserably.

Which is why I am proposing that we try a new tack. I am suggesting that the poster boy for the dangers of global warming should be Hollywood bad boy Charlie Sheen.

Why Charlie Sheen? Not because he is an especially egregious environmental criminal, certainly not on the order of BP or the notorious Koch brothers.

No, it's because Charlie Sheen personifies a certain attitude, call it an aggressive obliviousness to the harm caused to others, that is symbolized by his trademark facial expression: His smirk. You all know what I am talking about. It's been captured in countless ways by countless tabloid photographers on his way into and out of various courtrooms and rehab centers over the years.

It's a smirk that broadcasts boundless levels of arrogance, irresponsibility and self-centeredness, as well as a stubborn refusal to learn from his own mistakes or the experience of others. A smirk that trumpets, "F**k you, because I am a celebrity, you are a nobody, and I am very, very rich. And therefore the rules don't apply to me. Which means I can live like a total prick."

Charlie Sheen had the great misfortune to become the star of a hit sitcom and become the highest paid actor on television. Consequently, he commands enormous influence and can surround himself with a dedicated phalanx of enablers willing to indulge his every whim and fantasy, no matter how self-destructive.

That smirk, and the attitude it represents, sum up what we're really dealing with here. That's why I am nominating Charlie Sheen as the new face of environmentalism, the face I'd like to see on Sierra Club fund raising letters and Earth Justice e-mails.

Just to be clear, I have nothing against Sheen personally. In fact, I feel sorry for the guy. It feels odd writing such words about a man who earns more in an hour from his lame TV show than I earn in a year, who has had sex with an army of beautiful women, and who apparently thinks nothing about dropping $100,000 for a weekend's worth of cocaine and porn stars.

But Sheen's compulsive behavior, and the violence he has committed against women, clearly indicates that something is very broken about this man. Over the years, because of his extreme wealth and recklessness, he has probably ingested literally millions of dollars worth of high-quality cocaine, in addition to other stimulants.

As addiction experts will tell you, the consumption of so many powerful stimulates causes depression and and the disruption of the brain's reward system. Dopamine and other important neurotransmitters are badly depleted, resulting in an often incurable condition called anhedonia, or the inability to experience pleasure from such normally pleasurable activities as food, social interaction and sex. People who suffer from this problem often lose their will to live. Judging from Sheen's erratic behavior, that could be his current fate. In other words, he's made his life a perpetual hell.

Which is another reason Sheen should be environmentalism's new poster boy. He is a human train wreck, a burnt-out case, and an apt metaphor for how we are treating this planet. If we want to avert his fate, then we all need to act fast.

Dave-

Thanks again, and I'm not sure the flattery is entirely warranted, but thank you.

You're right, both methods are needed. The thing is, I agree with you that most people think they have enough information, and will not do something until it's economically sensible to do so. But that's the problem, from my perspective: if we wait until it's economically sensible to make drastic changes, it may very well be too late. From a capitalist perspective, scarcity = value/profit, so there is a large incentive to keep on producing dwindling resources, even where a clear substitution does not (yet?) exist.

I guess for me, it comes down to the inescapable fact that what is unsustainable, by definition, will not be sustained. I just want people to think about what would happen if they were forced to do without water and power, as the residents of El Paso recently had to do as a result of cascading failures. Or if food inflation hits in the first world, as my local news began warning of today, as well as the Christian Science Monitor, saying that

Food does not always come from the grocery store at prices that are affordable, and water does not always come from the tap. What's the backup plan?

I'm all for pursing technological advancements to ease the burden, but we need a credible plan in the meantime. And I think individuals should be pursuing their own food/water security, if nothing else just for the sake of redundancy.

Thanks for you thoughtful comments!

Mike:

Bravo!

Whether we are screwed or not, the only conclusion that I can come to is that we have to act as though we are not completely screwed if we have any chance of saving us from ourselves. But I think it will require more than a P.R. campaign, we need a full-court-press, the asteroid is headed towards us, hail-mary pass kind of effort.

I like your Charlie Sheen idea in a twisted kind of way. BTW- even Charlie Sheen thinks there are more important things going on in the world than his carryings-on:

Big picture time: We are living in a golden age, prosperous in our profligate consumption of irreplaceable resources. We can choose to use what is left of these resources to keep comfortable, or to use them to find more.

It will take an enormous investment to mine planetary space (asteroids, etc) and set up power stations that efficiently use the sun (outside of the atmosphere). But if we don't do it now, we won't have the wherewithal to do it later.

If we really want to sustain our species and our high level of civilization beyond this century, then we must get off this rock and look around. Cutting back just delays running out.

Malthus was not far off on how many people can survive, once fossil fuels, fissionables, and other rare metals run out. And mere survival is a step below living.

Consider what legacy we plan to leave.

Check out this version of elegant sustainability. http://www.yankodesign.com/2011/02/04/one-liter-l… Very clever. Maybe we need to build a world of machines like this around us to keep us aware of the need to live sustainably.

Dan: If we lived and procreated responsibly, we could maintain huge numbers of humans on this planet for thousands of years. I have yet to see any feasible plan for having humans live for any significant amount of time other than on earth. It sounds like you've given up on the idea that humans can educate themselves and live responsibly. It sounds like you are resigned. Some days, I am too.

Add Biology Nobelist Christian De Duve to the list of eminent scientists warning of our extinction. He says it's not our fault though, it's in our genes at this point:

He also speaks of birth control as an imperative, which is relevant to another post here at DI garnering a lot of comments.

A new paper in Nature asks "Has the Earth's sixth mass extinction already arrived?" (subscription required)

While leaving some room for optimism, the authors <a href="http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/2011-03-02-next-mass-extinction_N.htm?csp=34news&utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+usatoday-NewsTopStories+%28News+-+Top+Stories%29" rel="nofollow">also sound a very cautionary note: