Intrigued by my review of numerous articles on neural plasticity, I concocted a simple experiment that had dramatic results. I set out to see whether I could cause people to have the illusion that a cheap rubber hand could “become” their own hand. Over the past few years, I’ve run this experiment on about a half-dozen people, just out of curiosity. Most of my “subjects” found that the experience was “creepy,” in that it appeared that the rubber hand “became” their own hand. It’s an do-it-yourself artificially-induced out-of-body experience.

Here’s how I ran my experiment. Step one is to buy a rubber hand, the creepy kind often used in gags.

Here’s one place where you can buy a fake hand. Alternatively, here’s a site that teaches you how to make your own rubber hand. You’ll also need to bend a coat hanger into a “Y” shape.

Finally, you’ll need a simple barrier, such as a large book. That’s all the equipment you’ll need. Here’s how you run the experiment.

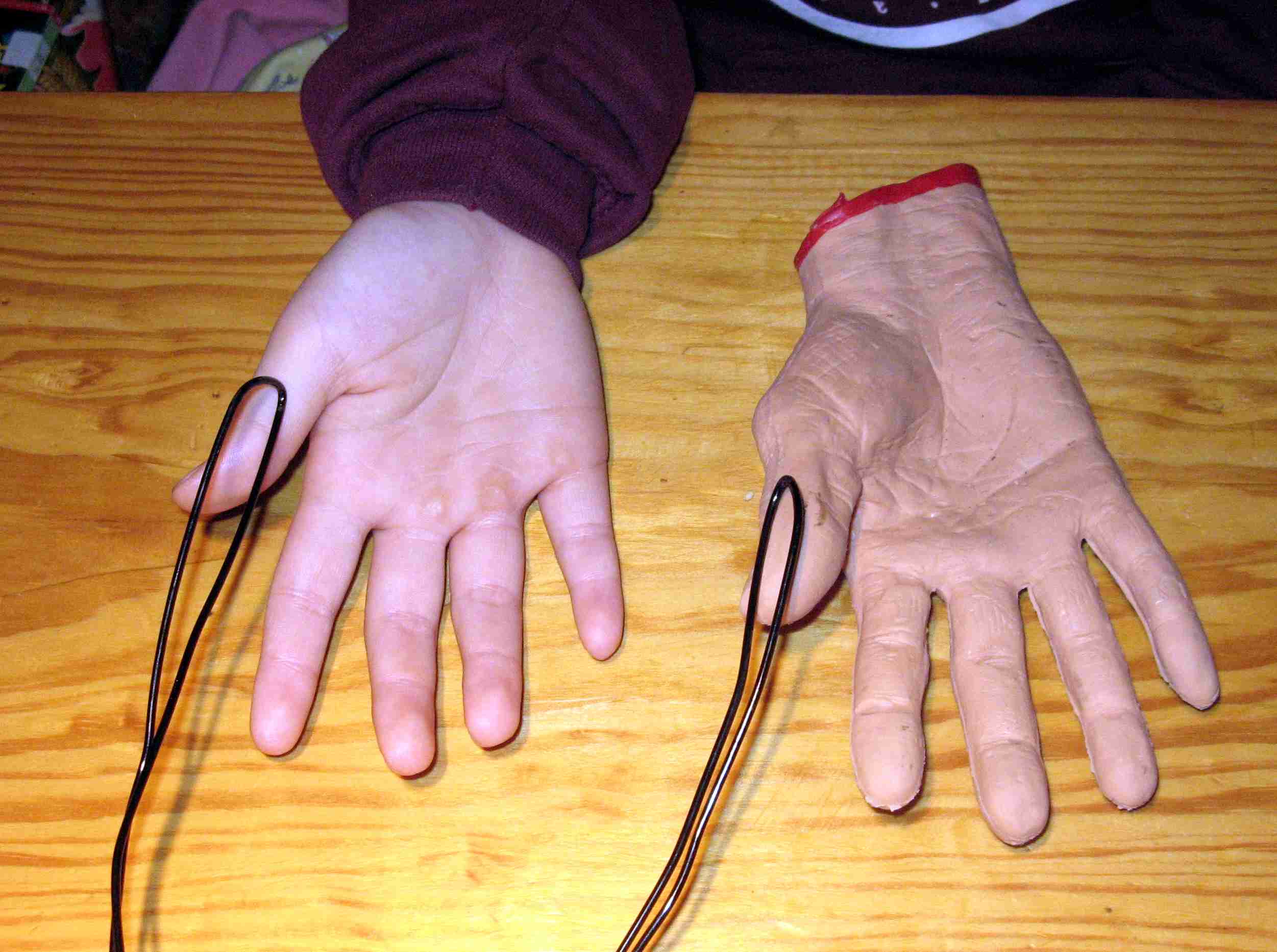

Put the rubber hand side-by-side with the person’s same-side real hand.

You’ll be using the “Y” shaped coat hanger to touch precisely the same part of the rubber hand and the subject’s hand simultaneously. Move the hanger around and tap on or stroke a wide variety of corresponding parts of the two hands.

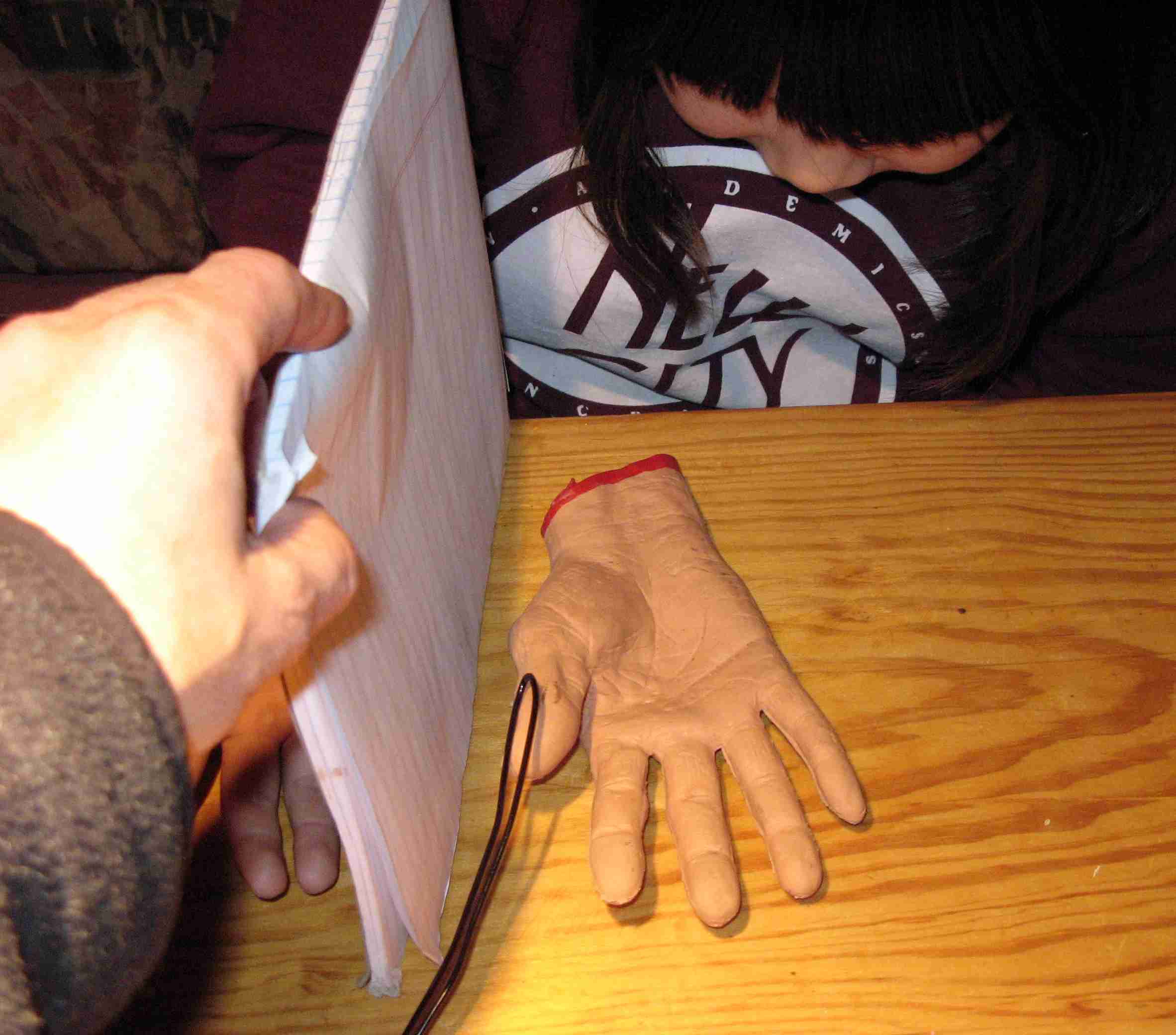

While you tap on the same portions of each hand, the subject should only be looking at the rubber hand–that’s why you’ll need some sort of barrier. As you can see below, even a pad of paper will do the trick.

You’ll need to do this tapping and stroking of the two hands for a minute or two before the subject experiences the illusion. You’ll want to exercise great care that the ends of the hanger always touch or stroke the corresponding parts of the real hand the the rubber hand simultaneously so that the illusion is repeatedly enhanced.

Most subjects will be laughing as you start. After a minute or two, they will start commenting that “something” is happening. You’ll hear comments like “that’s weird.” After the effect is well established, you can have a bit of fun. I end the experiment by smashing the rubber hand with my fist, which causes the subject to react with panic. Just be patient enough so that the subject reports that the rubber hand has eerily “become” his or her own hand. The illusion is so strong that it occurs even when you tell the subject what you are doing and why.

[I see now that my crude experiment has actually been done more rigorously here and here (“When a person is watching a fake, rubber hand being stroked and tapped in precise synchrony with his or her own unseen hand, the person will, within a few minutes of stimulation, start experiencing the rubber hand as an actual part of his or her own body. In

part, this illusion illustrates the importance of visual information in specifying limb location and constructing the body image”). Now that I see this experiment in detail, I might want to change the way I do it–in particular, I might want to use two small paint brushes instead of the coat hanger.]

Recent sophisticated studies reported by Discover Magazine demonstrated the same phenomenon on a larger scale: in these experiments, the subjects’ minds appeared to move into a mannequin. These studies, “The Experimental Induction of Out-of-Body Experiences” by H. Henrik Ehrsson and “Video Ergo Sum: Manipulating Bodily Self-Consciousness” by Bigna Lenggenhager et al., were both published in the August 24, 2007, issue of Science.

Henrik Ehrsson of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, actually ran two experiments in which he successfully altered the subjects’ perception of their location in space.

He seated 18 healthy individuals and filmed their backs with a pair of video cameras. While filming, he gave the subjects a stereoscopic view of their backs, using goggles that captured the video from both cameras. Ehrsson then repeatedly touched each person’s actual chest with one rod while, with another rod, he jabbed toward a point below and in front of the two cameras that corresponded to the “virtual chest” of the image projected into the goggles. With the shift in perspective through the goggles, subjects reported that they felt as though they were physically embodying a space six and a half feet behind where they actually were.

Ehrsson ran a second experiment, in which he tested to see if the subjects would respond as if they were located in that “false” position.

He outfitted subjects with sensors that monitor electrical conductance, then arranged the same setup and repeated the rod movements he had conducted in the first experiment. When he swung a hammer toward the two cameras at a point corresponding to the center of the face of the camera-generated illusory body, the subjects’ skin showed a spike in electrical conductance—a sign of increased sweating and emotional arousal—and they reported immediate anxiety. In a separate experiment, Bigna Lenggenhager placed a camera six and a half feet behind the back of each of 14 participants wearing 3-D video goggles.

Here’s a diagram illustrating Ehrsson’s experiment:

An experimenter then stroked their backs with a large pen so they could simultaneously see and feel their backs being caressed. Blanke guided the subjects backward and then asked them to return to their previous position. Participants overshot the distance by an average of 10 inches, moving closer to the position of their “virtual” bodies. He also filmed the back of a mannequin and projected the image into the subjects’ goggles. “They felt that the mannequin’s body was their body,” Blanke says.

To learn more about the Lenggenhager experiment, check out the full text of the article at Science.

To manipulate attribution and localization of the entire body and to study selfhood, we designed an experiment based on clinical data in neurological patients with out-of-body experiences. These data suggest that the spatial unity between self and body may be disrupted, leading in some cases to the striking experience that the global self is localized at an extracorporeal position. The aim of the present experiments was to induce out-of-body experiences in healthy participants to investigate selfhood. We hypothesized that, under adequate experimental conditions, participants would experience a visually presented body as if it were their own, inducing a drift of the subjectively experienced bodily self to a position outside one’s bodily borders. . . . Our results show that humans systematically experience a virtual body as if it were their own when visually presented in their anterior extra-personal space and stroked synchronously.

Here is Ehrsson’s explanation of what happened in his experiments:

“We now understand how the brain combines information from the eyes and from the skin to compute or determine where the self is located in space,” Ehrsson says. Both experiments show how easily the brain can be tricked or how it “cheats,” he says, using memory and prior experiences to fill in data gaps. Beyond helping us understand some fundamental elements of the out-of-body experience, this research could make for better game play. “We think this will enhance virtual reality applications in education, games, and therapy,” Ehrsson says. “People will feel that they are genuinely there in a virtual world.”

The experience of “self” actually occurs on at least two levels. The most forceful experience of “self” is at a purely physical level, a “self” that is anchored by a constant stream of neural stimulation experienced by one’s own body. Under normal conditions, these neural sensations anchor each “self” to a specific body. Each of us normally “inhabits” his or her own body. The above experiments (and my simple version of the hand experiment that you can try at your own home) show that even this basic physiological version of self can be dramatically shifted away from your own body.

There is another level of self that normally extends out beyond one’s own body. This “extended self” is anchored by intellectual and social connections. This “extended self,” on which Andy Clark has eloquently written, extends well beyond skin and skull.

Our extended selves are located relative to our belongings, the information upon which we rely (our favorite websites, books, songs) and the people with whom we react. Extended selves are already portable virtual selves (much more portable than our physical selves). People who are more highly educated and better-traveled tend to feel more connected to people other than themselves and their own families. It seems, then, that the scope of our extended self defines our moral realm of concern. It seems to me that my realm of moral concern is actually another way of describing the extent to which “I” am invested in the world beyond my own physical self.

I am tempted to extrapolate here—what follows is highly speculative. If something so basic as a physiologically-experienced version of “self” can be shifted by simple trickery, can’t the extended self, which already “resides” well beyond the physical body, also be relocated?

Perhaps this portability (of our body-based selves) reminds us that we can train ourselves to “relocate” our extended selves too, in order to encompass people and issues far beyond our own immediate personal interests. Moral realms of concern are certainly highly variable among people. Some people are concerned only about their immediate physical wants and needs, whereas others try mightily to consider the needs of everyone else on the planet when they make decisions.

This great variability suggests that each person’s realm of concern can shifted in such a way that each person can choose to allocate attention well beyond his or her bodily self (or not). Perhaps future studies can explore the triggers that broaden (or narrow) the scope (the “location”) of a person’s extended self—the scope of his or her realm of moral concern.

is it possible you can send me a picture of the back of it and is that the same one as the one that is for sale

Sorry – I don’t have any more information on the rubber hand I used. Any life-sized rubber hand will do.

Here’s more on the rubber hand, as well has how to shrink your body or turn your arm into cement.

“No matter how much of a critical thinker you consider yourself, your brain is pretty gullible. With a few minutes and a couple of props, your brain can be convinced that one of your limbs is made of rubber or invisible, or that your whole body is the size of a Barbie doll’s. All these illusions depend on your senses of vision and touch interacting. But a new illusion trades sight for sound. By hearing the sound of a hammer striking marble each time it tapped their hands, subjects came to feel that their limbs were made of stone.”

http://theweek.com/article/index/258896/how-to-flirt-according-to-science