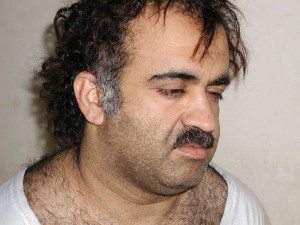

A debate is raging over the wisdom of the administration’s decision to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) in a civilian court in New York City. Those opposed to the decision assert that it’s simply too dangerous, that a military tribunal in Guantanamo would be better, and that it’s foolish to afford any constitutional protections to terrorists. They argue that KSM and other terrorists should be held under the law of war– that their actions were not crimes, but rather acts of war and are therefore undeserving of access to our normal criminal justice system. There is so much wrong with this way of thinking, it’s difficult to know where to begin to refute them. I think I’ll go on a point-by-point basis.

Those opposed to civilian trials initially cite security concerns. For example, see this bipartisan letter from six senators to Attorney General Eric Holder. The typical argument goes like this:

The security and other risks inherent in holding the trial in New York City are reflected in Mayor Bloomberg’s recent letter to the administration advising that New York City will be required to spend more than $200 million per year in security measures for the trial. As Mayor Bloomberg and Police Commissioner Kelly know too well, the threat of terrorist acts in New York City is a daily challenge. Holding Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s trial in that city, and trying other enemy combatants in venues such as Washington, DC and northern Virginia, would unnecessarily increase the burden of facing those challenges, including the increased risk of terrorist attacks.

They assert that there would be an increased risk of terrorist attacks based on holding trials. Why? What’s the justification for this assertion? Terrorists will be so outraged at our decision to abide by our laws that they will strike out? They prefer the current system of indefinite detention without charges? They don’t already consider New York City a terrorist target? If anything, this assertion is contradicted by another claim– that terrorists cannot wait for a trial, because they will use it as a pulpit to expound on the wrongs of the USA. From the same letter, one paragraph above the previous citation:

We are also very concerned that, by bringing Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and other terrorists responsible for 9/11 to the federal courthouse in lower Manhattan, only blocks away from where the Twin Towers once stood, you will be providing them one of the most visible platforms in the world to exalt their past acts and to rally others in support of further terrorism. Such a trial would almost certainly become a recruitment and radicalization tool for those who wish us harm.

So, they are going to use the trial as a recruitment and radicalization tool by exalting their past acts, but they might just decide to blow up New York instead? Which is it? I suppose they could do both, perhaps those wily terrorists will wait until the very last day of the trial when we find them guilty, and then they will strike? Oh, but those opposed to civilian trials also point out that we might not get a conviction. They argue that once we allow constitutional and legal protections for terrorists, they will use those against us and they might be found not-guilty. See, for example, this exchange from MSNBC:

Savannah Guthrie: Let’s move on to terror politics. This has very much been in the news. Assuming the administration believes it’s right on the policy, for example, that KSM should be tried in civilian court as opposed to military commissions, are they getting the politics wrong here? It doesn’t seem like anyone is coming out on their side and forcefully defending these decisions.

Mike Whitaker: Well, first of all, just on the legal issue, frankly, I think they’re a little bit confused because on the one hand they’re saying that the argument for trying Khalid Shiekh Mohammad in a civilian court is that it gives it more legitimacy. Well, what’s the legitimacy come from? It basically comes from the presumption of innocence. Meanwhile, you have Gibbs and Holder, and so forth, guaranteeing a conviction. I’ve been told-

Chuck Todd: Guaranteeing the death penalty!

Whitaker: Right, and I’ve been talking to prosecutors in New York, who have tried a lot of these cases, and say you never — in a civilian court with a jury — you can never guarantee anything. I think on the politics, frankly, I think this is a pure, self-inflicted wound.

Oh no, there’s a chance they might not be convicted! Not to worry though, the guilty verdict is a foregone conclusion:

Mr. Obama himself responded to criticism by suggesting that what he had in mind was a series of show trials, in which the verdict and punishment were foreordained.

When NBC’s Chuck Todd asked him in November to respond to those who took offense at granting KSM the full constitutional protections due a civilian defendant, the President replied: “I don’t think it will be offensive at all when he’s convicted and when the death penalty is applied to him.” Mr. Obama later claimed he meant “if,” not “when,” but he undercut his own pretense of showcasing the fairness of American justice.

Although not discussed in detail, you will occasionally find someone who is willing to mention the elephant in the room. That is, given that we’ve tortured many of these suspects, how much of our intelligence is admissable in court?

There is a real possibility, too, that convictions would be overturned on technicalities. KSM and other prospective defendants were subjected to interrogation techniques that, while justifiable in irregular war, would be forbidden in an ordinary criminal investigation. When Senator Herb Kohl, a Wisconsin Democrat, asked Attorney General Eric Holder what the Administration would do if a conviction were thrown out, Mr. Holder said: “Failure is not an option.” A judge may not feel the same way, and the Administration is derelict if it is as unprepared for the contingency as Mr. Holder indicated.

Torturing someone is now a “technicality.” The “War on Terror” is apparently an “irregular war”, where torture is “justifiable”, although it would be forbidden in an “ordinary criminal investigation.” But why should that be the case? If we accept that torture works, then why shouldn’t we allow it in ordinary criminal investigations? If we don’t see anything wrong with torture per se, why not expand its use? Perhaps because the results show that it doesn’t “work”, at least if the goal is to get the truth from a suspect:

Self-proclaimed Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed told U.S. military officials that he had lied to the CIA after being abused, according to documents made public Monday. The claim is likely to intensify the debate over whether harsh interrogation techniques generated accurate information.

Mohammed made the assertion during hearings at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where he was transferred in 2006 after being held at secret CIA sites since his capture in 2003.

“I make up stories,” Mohammed said, describing in broken English an interrogation probably administered by the CIA concerning the whereabouts of Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. “Where is he? I don’t know. Then, he torture me,” Mohammed said of his interrogator. “Then I said, ‘Yes, he is in this area.’ “

Mohammed also appeared to say that he had fingered people he did not know as being Al Qaeda members in order to avoid abusive treatment. Although there is no way to corroborate his statements, Mohammed is one of the militants whom the CIA repeatedly subjected to the simulated-drowning technique known as waterboarding.

Don’t forget the recent admission from a CIA agent that he lied when he spoke about how effective waterboarding was.

Further, consider the multi-tiered system of justice that opponents of civilian trials seem to be in favor of adopting. That is, we will use civilian courts only when we can guarantee a guilty verdict. If we cannot guarantee a guilty verdict, we will simply continue to hold those accused indefinitely without any charges whatsoever (see here, here, and here for Glenn Greenwald’s devastating commentary on this point).

Similarly, there has been a great deal of criticism of the administration’s decision to take the Christmas day Underwear-bomber, Umar Abdulmutallab, into the normal criminal justice system. For example, see Time‘s Joe Klein’s recent commentary:

In the Washington Post today, former CIA director Mike Hayden has a column lamenting the fact that the Undiebomber was read his Miranda rights after only 50 minutes of negotiation. He is absolutely right: the bomber is an enemy combatant. He doesn’t have Miranda rights. It is entirely possible that we lost valuable intelligence as a result of this stupidity. We don’t torture anymore and that is good. The notion that we don’t even properly interrogate those who attack us seems unbelievable.

However, this decision has not impacted our intelligence collecting capabilities. Authorities indicate that Abdulmutallab has been providing a great deal of valuable and actionable intelligence, despite being Mirandized. Attorney General Eric Holder has also defended the decision to put Abdumutallab into the criminal justice system in a five-page letter to some senators who expressed opposition to the decision. Some relevant excerpts:

Since the September 11,2001 attacks, the practice of the U.S. government, followed by prior and current Administrations without a single exception, has been to arrest and detain under federal criminal law all terrorist suspects who are apprehended inside the United States.

…

In keeping with this policy, the Bush Administration used the criminal justice system to convict more than 300 individuals on terrorism-related charges.

…

The initial questioning of Abdulmutallab was conducted without Miranda warnings under a public safety exception that has been recognized by the courts. Subsequent questioning was conducted with Miranda warnings, as required by FBI policy, after consultation between FBI agents in the field and at FBI Headquarters, and career prosecutors in the U.S. Attorney’s Office and at the Department of Justice. Neither advising Abdulmutallab of his Miranda rights nor granting him access to counsel prevents us from obtaining intelligence from him, however. On the contrary, history shows that the federal justice system is an extremely effective tool for gathering intelligence. The Department of Justice has a long track record of using the prosecution and sentencing process as a lever to obtain valuable intelligence, and we are actively deploying those tools in this case as well.

Opponents of civil trials go on to assert that military tribunals are a more appropriate or safer venue for trials. But if history is any guide, civilian trials provide better outcomes:

But administration officials note that 348 international and domestic terrorists are being held in federal prisons after they were convicted in civilian criminal trials. By contrast, in the eight years since the Bush administration first set up military commissions, only three Guantánamo detainees have been convicted, in part because of legal challenges to the tribunals. Two of the three received modest sentences and are now free.

Eric Holder’s letter provides a similar analysis in respect to holding the accused under the law of war:

In fact, two (and only two) persons apprehended in this country in recent times have been held under the law of war. Jose Padilla was arrested on a federal material witness warrant in 2002, and was transferred to law of war custody approximately one month later, after his court-appointed counsel moved to vacate the warrant. Ali Saleh Kahlah AI-Marri was also initially arrested on a material witness warrant in 2001, was indicted on federal criminal charges (unrelated to terrorism) in 2002, and then transferred to law of war custody approximately eighteen months later. In both of these cases, the transfer to law of war custody raised serious statutory and constitutional questions in the courts concerning the lawfulness of the government’s actions and spawned lengthy litigation. In Mr. Padilla’s case, the United States Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit found that the President did not have the authority to detain him under the law of war. In Mr. AI-Marri’s case, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed a prior panel decision and found in a fractured en banc opinion that the President did have authority to detain Mr. Al Marri, but that he had not been afforded sufficient process to challenge his designation as an enemy combatant. Ultimately, both AI-Marri (in 2009) and Padilla (in 2006) were returned to law enforcement custody, convicted of terrorism charges and sentenced to prison.

Understanding all of this, what reasons remain for abandoning our criminal justice system in favor of secret tribunals, torture, and indefinite detention? The legal system has a proven track record of success in dealing with the crime of terrorism, why must we ignore it?

Finally, we must confront what should be a central issue in our handling of suspected terrorists. Namely: why do we keep letting them in the country? For all the discussion of “failure to connect the dots”, the real truth is that federal counter-terrorism officials insisted that Abdulmutallab be allowed into the country:

The State Department didn’t revoke the visa of foiled terrorism suspect Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab because federal counterterrorism officials had begged off revocation, a top State Department official revealed Wednesday.

Patrick F. Kennedy, an undersecretary for management at the State Department, said Abdulmutallab’s visa wasn’t taken away because intelligence officials asked his agency not to deny a visa to the suspected terrorist over concerns that a denial would’ve foiled a larger investigation into al-Qaida threats against the United States.

“Revocation action would’ve disclosed what they were doing,” Kennedy said in testimony before the House Committee on Homeland Security. Allowing Adbulmutallab to keep the visa increased chances federal investigators would be able to get closer to apprehending the terror network he is accused of working with, “rather than simply knocking out one solider in that effort.”